A blog post by Jovia Salifu (postdoctoral researcher on the Archive of Activism project)

Gender activists and practitioners will remember the year 1975 as the United Nation’s International Women’s Year. As an initiative of the UN Commission on Women, it was part of a broader effort that included the first World Conference on Women in Mexico City in June/July 1975. In Ghana, this announcement was greeted with great enthusiasm from various sections of society, including state and non-state organisations as well as individuals of both sexes. It evoked a sense of urgency in public discourse on the meaning of equality in the relations between males and females, and debate about whether such equality was desirable in the country. On the evidence of public pronouncements and exchanges, there appeared to be overwhelming support for gender equality, although there were a few dissenting voices urging caution and admonishing against rhetoric that would encourage insubordination in the women folk. Considering the level of public interest in the International Women’s Year, and the debates that it inspired, the year 1975 could be seen as a watershed moment in the pursuit of gender equality in Ghana.

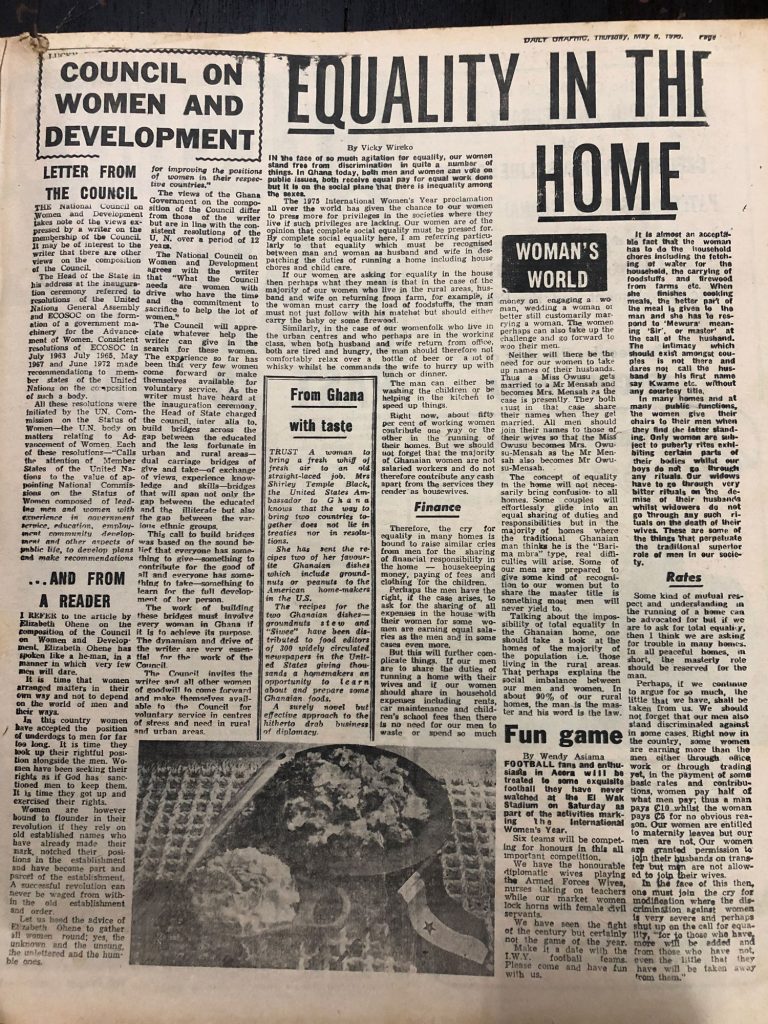

In the national newspapers of this period, the idea of an International Women’s Year attracted much comment from editors and readers alike. The Women’s Page of the Daily Graphic, for example, regularly featured editorials and readers’ letters about the relevance of the women’s year and gender issues in general. Opinions expressed in these pieces often sparked further comment from readers in subsequent issues and in other publications, with the resulting conversations extending over time and cropping up in different forums. Notably, these public exchanges were not devoid of emotion, as readers answered every provocation in equal measure.

One such thread began with a piece by Vicky Wireko on the Women’s Page of the Daily Graphic on May 8, 1975. Titled ‘Equality in the home’, the article opened with a call for true equality between the sexes in the spirit of the International Women’s Year. According to Vicky Wireko, this sort of equality must apply to every aspect of life, including the equitable sharing of household chores and financial responsibilities between men and women. Thus, a man should not ‘comfortably relax over a bottle of beer or a tot of whisky whilst he commands the wife to hurry up with lunch or dinner.’ If such a total equality were achieved, she argued, there would be no need for women to adopt their husbands’ surnames upon marriage. As true equals, both husband and wife could combine their surnames to make a compound surname. Similarly, there would be no need for men to solely bear the responsibility for initiating marriage and paying for the ceremony.

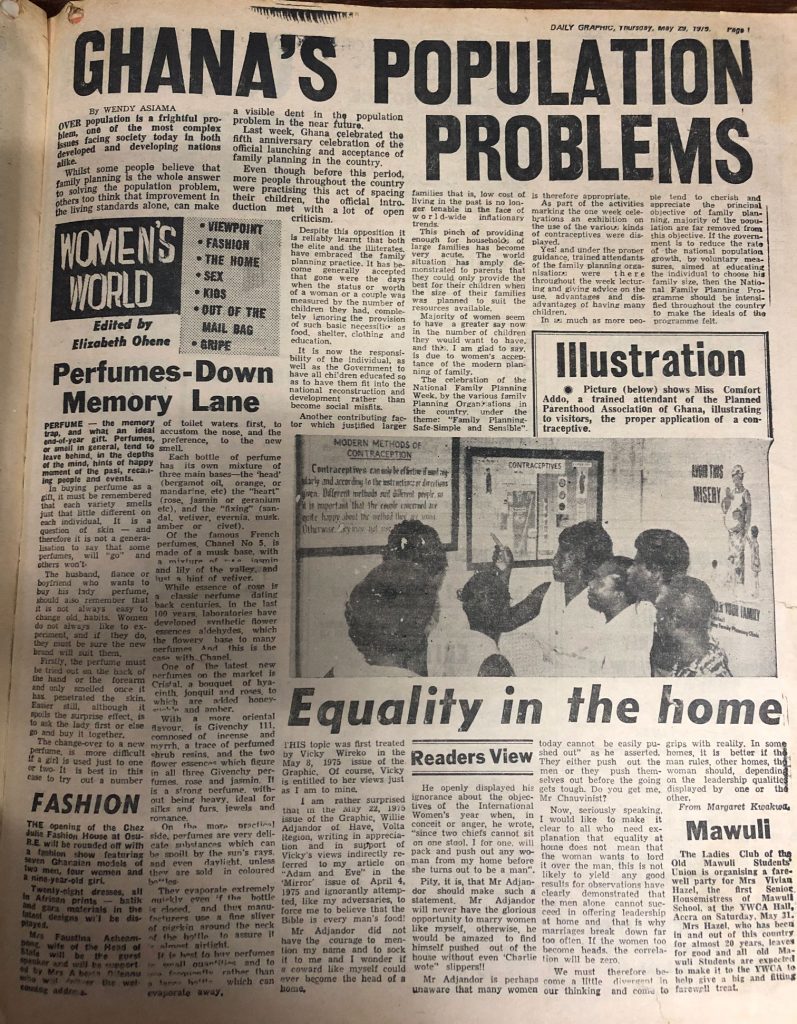

Despite these radical propositions, the writer did not underestimate the enormity of the task of changing attitudes in a male-dominated society. In this context, she recognised that the resistance to change would be enormous, and success could only be achieved through subtlety in order not to provoke angry backlash from men. With that said, she concluded her article on a note of circumspection, recognising that absolute equality was nearly impossible. After all, women also enjoyed some privileges on account of their gender. At this time, only female public-sector employees were allowed to seek a transfer of location for family reasons (usually to join their husbands), to obtain maternity leave from work, and to pay half the local rates that men paid. These sentiments were echoed by Wendy Asiama in the Daily Graphic of May 15, 1975. Beginning on a similar note of underlining the significance of the women’s year, Wendy Asiama cautioned that it must not be perceived as a weapon against men, but rather an opportunity for women’s groups to work towards improving the conditions of women.

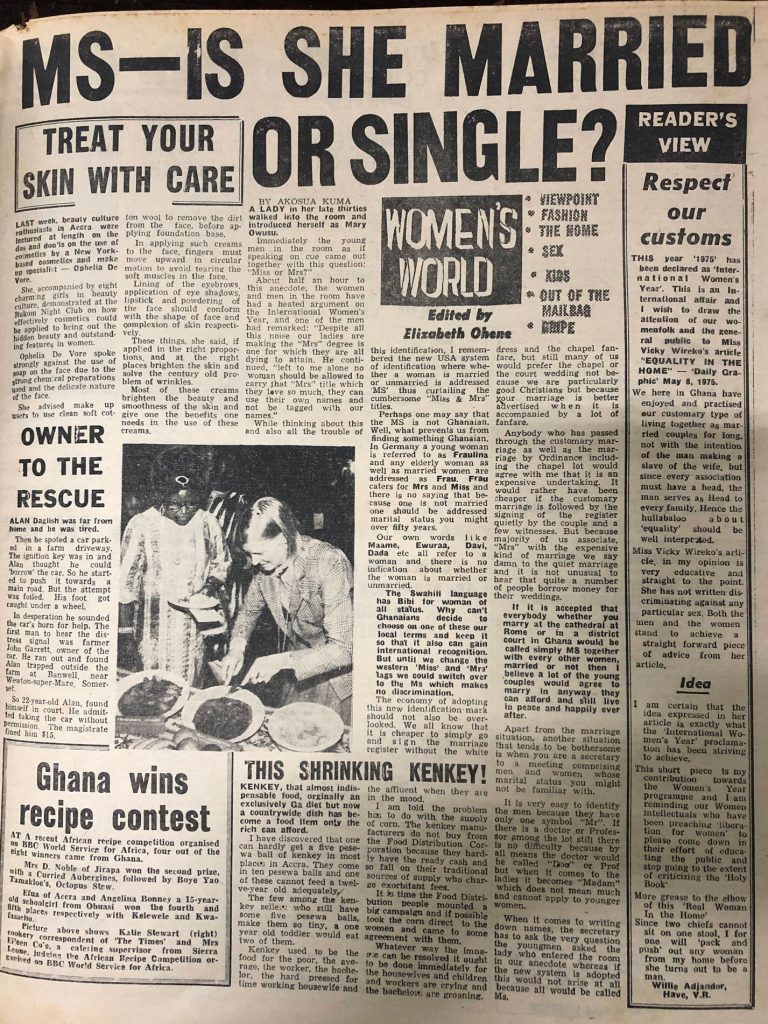

Within days, it was clear that both Vicky Wireko and Wendy Asiama had correctly anticipated the reaction of some men to the persistent calls for change. The rejoinder of Willie Adjandor of Have in the Volta Region in the same newspaper (May 22) began with a polite acknowledgement of the significance of the women’s year and the accompanying calls for equality. However, his main point was an admonition against the temptation to attack ‘custom’ by overemphasising the equality between men and women. This, he argued, had the danger of turning the women’s year into an anti-male campaign instead of the progressive movement it was supposed to be. In the home, the man ought to remain the head, a position he must exercise fairly without abusing his authority. At the same time, the woman must not seek to dominate man. ‘Since two chiefs cannot sit on one stool, I for one will “pack and push” out any woman from my home before she turns out to be a man,’ he concluded.

By the next week, Willie Adjandor had earned himself a strong rebuttal from another reader, Margaret Kwakwa, who counted him among her ‘adversaries’. She had been provoked by what she described as Willie Adjandor’s indirect response to her article published in The Mirror of April 4, 1975. Characterising Willie Adjandor’s opinions as chauvinistic and ignorant, she argued that it was absurd to demand that men lead at all times. After all, there were women who had shown themselves to be more capable than men and it would be a shame to deny them the opportunity to lead. Leadership should not be based on sex but rather on capabilities, she emphasised. Throughout the piece, she addressed Willie Adjandor directly, answering his threat to throw any insubordinate woman out of his house by claiming that she was more than capable of doing same or even worse to a man who overstepped his bounds: ‘Pity, it is, that Mr Adjandor should make such a statement. Mr Adjandor will never have the glorious opportunity to marry women like myself, otherwise, he would be amazed to find himself pushed out of the house without even “Charlie wote” slippers!!’[1]

The year 1975 serves as a landmark moment when a significant turn was made in the campaign for women’s rights worldwide. Ghanaians recognised this moment and took full advantage of the public platforms available to them to join in the debate. The International Women’s Year ushered us into a lively moment of conversation when ordinary citizens like Vicky Wireko, Wendy Asiama, Willie Adjandor, and Margaret Kwakwa expressed their viewpoints and sought to influence others, in the public space. The significance of 1975 is manifested every year, in our ongoing celebration of March 8 as International Women’s Day. It remains a very important chapter in the history of gender activism in Ghana.

Jovia Salifu

[1] In Ghana, bathroom slippers are commonly referred to as Charlie wote. Margaret was therefore suggesting that Willie would be forced to leave barefoot.

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?