Dr Pietro Tricoli writes about his work in power electronics and how it plays its part in the decarbonisation agenda.

If you think about rail decarbonisation you’re likely to think, “Electric trains.” You will have read in this blog series that we need the right amount of the right kind of electricity to power our transport and that this varies according to where the train is in relation to topography, acceleration, etc. This is where power electronics comes in: it is the field of study which works out how to harvest the maximum energy from a source (e.g. a wind turbine), convert it so it can be delivered through the grid or an energy storage system and then convert it again, into the kind of energy needed by the device.

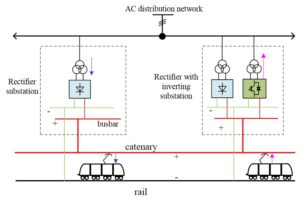

Most electric trains run on an external power supply – overhead lines or a third rail supply. Others use on-board power sources that do not use combustible fuels, such as fuel cells or electrochemical batteries. For powered electric trains, the power supply is either DC or single-phase AC. For independently-powered trains, the power source is DC. However, trains’ traction motors use almost invariably three-phase AC, which means we need to convert the supply to what is needed. For electric trains it also means we need to work out how to electrify the network and provide the right amount of power needed by a train at any one point in its journey. This is where Pietro’s work comes in: his expertise is to find out how to adapt the characteristics of the power source to those of the power user, and to do it efficiently.

The rail industry’s Carbon footprint derives from energy used for traction (running trains) and non-traction (stations, operations, signalling systems, etc), using electricity generated mostly from burning fossil fuels. If we can connect traction supplies (e.g. overhead lines powered by the grid) to non-traction applications we can make use of energy-harvesting techniques popular on trains. The most common of these techniques is regenerative braking: many modern trains will harvest the energy taken from the train during braking and store or return it to its power supply for later use. Power electronics allows us to do this and thus reduce the consumption from the fossil fuel-powered electricity distribution network.

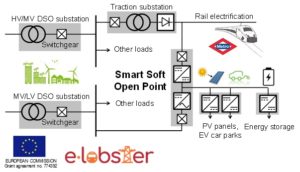

Furthermore, railways will be able to play an even more important role in future transport systems if they can be more integrated with road transport. There is an evident opportunity to integrate electric railways with electric mobility to achieve 100% clean journeys. This would be facilitated by adding a sufficient number of charging points at railway station car parks and by using clean electricity sources such as solar photovoltaics. Doing all this means we can minimise the demands made on the grid infrastructure as well as implementing vehicle-to-grid approaches to level the consumption of electricity of railway stations and maximise the energy generated from renewable sources. Pietro is technical coordinator of E-Lobster, a European research project that uses power electronics and energy storage as key technologies for managing energy exchange between power distribution grids and electric railways.

Other current power electronics projects are on fast-charging technologies for electric vehicles and how we can use clean energy to achieve this. Pietro is also leading the charging infrastructure theme of the Decarbonising Transport through Electrification (DTE) Network+, a major industry-academia network which brings together academia, industry and the public sector to address the challenges of an electrified, integrated transport system across the automotive, aerospace, rail and maritime sectors.

Read more about Pietro’s work on the website and contact him directly on email