By Dr Sarah Ball, Dr Robert Lepenies, Professor Holger Strassheim, and Dr Jessica Pykett

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vital role that behavioural expertise and behaviourally-informed public policies can play in keeping people safe and in understanding risky or health-promoting behaviours, such as compliance with social distancing rules. The public health decision making landscape is a complex one, involving policy makers from across multiple sectors, and at different levels of government. There is an urgent need for us to learn more about how ethical considerations have informed pandemic response policies, in times of crisis, in recovery strategies and more broadly. How does government make decisions regarding the design and implementation of these policies? How do governments use ethical frameworks to influence citizen wellbeing and outcomes, and balance these with compliance with the their regulatory goals? What kind of infrastructures exist to provide ethics advise to governments and what influence do they have?

On 25 March 2021 a scoping workshop was held with key stakeholders in order to gain better insight into how ethical expertise was shared during the COVID-19 pandemic decision making process in the UK. Key questions explored included the key pressures and constraints on decision making, institutions involved, and the principal ethical issues raised. The insights from this event will further inform a larger international research project on ‘Expertise and Ethics in Times of Crisis’ which compares the roles of expertise and ethics in Germany and the UK.

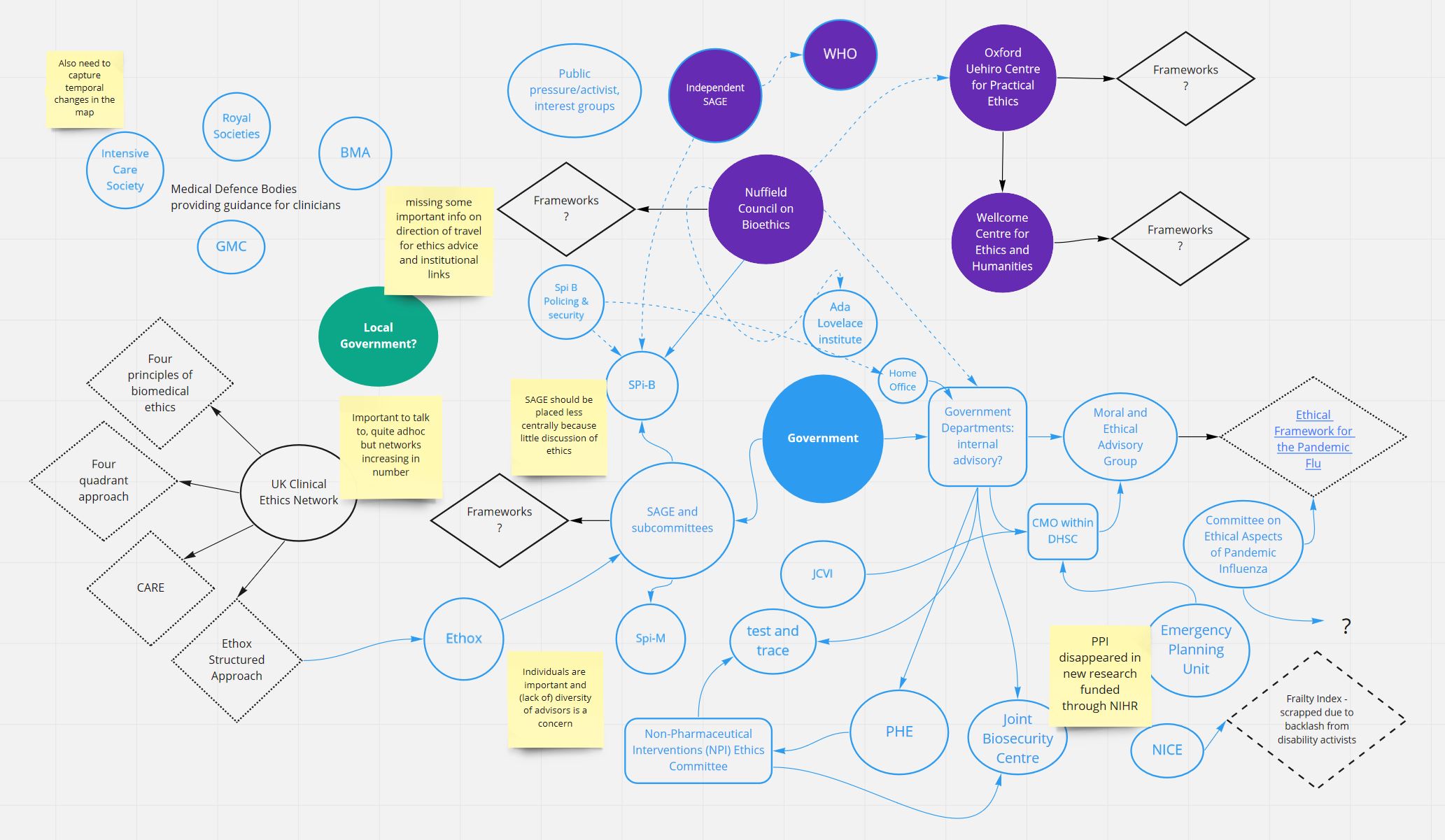

Participants were first provided with a rough map of the institutions involved in COVID-19 pandemic decision making (Diagram 1 – below). They were asked whether there were any gaps or missing organisations. They were also asked about how these organisations communicated with each other and with policy makers. The institutional map below was the result.

The relationships were many and varied, with a diverse range of institutions and organisations involved. Some individuals were also revealed as key connectors. One participant noted that there would be value in exploring the influence of public pressure and activism in driving government to seek advice on specific issues. This pressure could also come from other organisations. For example, the vaccination of prisoners was put forward as a special consideration by the JCVI (Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation), given that enclosure led to higher risk. This was driven by advocacy from across Prison and Probation Services, NHS and Public Health England (PHE), as well as public petitions.

Despite its centrality in the broader science advice landscape, there was a perception that SAGE (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) rarely engaged with ethical questions, and there were limited explicit references to ethical concerns in the meeting minutes. Participants reflected that in contexts like these, there was a risk that ethics can be seen as a regulatory hurdle getting in the way of action and risks decision paralysis.

Overall, it was agreed that the UK ethics advisory system for Government is relatively complex and unstructured. Unlike some other countries, there is no national ethical committee coordinating from the centre. Ethical advisory bodies that do exist lack authority over decision making. This lack of structure can lead to ad-hoc science advice and competitiveness amongst experts. However, this ad hoc approach may work to both help, as well as hinder, ethical debates. It hinders because lines of responsibility can be unclear, especially during a crisis. This can lead to further gaps in advice. However, it can also help, allowing for a diversity of voices and advocacy groups to contribute.

The institutional mapping process was followed with the discussion of the timeline of decision making during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Diagram 2 below). Participants were asked where key ethical ‘moments’ occurred.

Participants pointed to the important role played by key narratives. Some of these narratives included the inequalities of sacrifices made, the myth of solidarity (linked to the Cumming’s scandal). Another critical ethical moment was when the NICE ‘Frailty Index’ came under fire for its alleged use to ‘ration’ care for elderly and frail patients. Groups representing people with learning disabilities, autism or long-term, stable disabilities were at risk of disadvantage is hospitalised with COVID-19. Language was eventually changed but the key point was that language and narrative were very important in framing ethical issues.

One of the key challenges participants noted in the debate and discussion of ethics, in relation to the timeline, was the fear of these debates acting as an impediment to action. As ‘grit in the gears’. Is ethical debate a luxury, saved for when there is a surplus of time? Also, if ethical concerns are best considered when there is time to spare, why was there so little forward planning between the first and second wave? Many issues were left unexplored such as triage, hospitalisation priorities, support for employment that could not be done from home, vaccine certification etc. There was a time for these debates to happen, but they were seen to have passed government by.

In addition to mapping the institutions and timeline, several other interesting points arose during the workshop which relate to how ethics and expertise influence decision making in the UK. First, issues pertaining to clinical ethics were far more likely to be considered than broader ethical questions pertaining to societal or wellbeing concerns. Overall, there appeared to be a noticeable hierarchy of expertise, with advice from virologists, epidemiologists, or psychologists more likely to be sought after than social scientists or even engineers. There is a growing need for more transparency and understanding of both the institutional and personal linkages between advice giving bodies.

Second, there are questions to be asked regarding the role of the civil service in raising these concerns. Political actors can be averse to making overt decisions on values and tend to prefer a focus on ‘science’ and ‘evidence’. This approach tends to ignore the political component of scientific advice. However, as institutional capability and memory is lost within the civil service, and power shifts to advisors over civil servants, the ability to influence these decisions shifts yet further away from the public eye.

Finally, perhaps the most important point to takeaway from the workshop with wider implications for the intersection of wellbeing and public policies, was that we cannot always expect that ethical consensus is possible, or even desirable. Ethical debates are driven by values. These values need to be transparent, and debates need to be open to diverse voices. But how can researchers engage in these debates when there is resistance to any advice that risks contradicting the government’s position? The participants agreed that, given this challenge, future research should explore best practices for ethical debate and advice, rather than the ethical principles as an end in themselves.