With thanks to Nettes Derbyshire, Debra Gordon, Clare Harewood, Chantal Jackson, Jean-Claude Kabuiku, Toqueer Ahmed Quyyam, Marianne Walker and BVSC Research

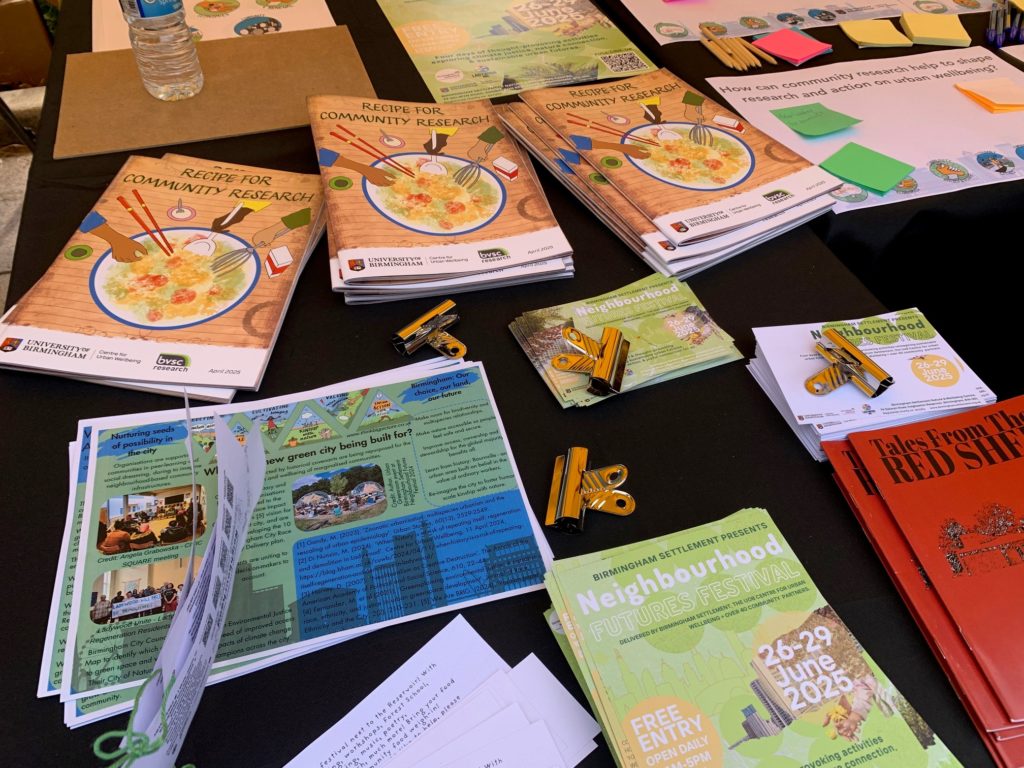

Over the summer of 2025 CUWb academics and community researchers were involved in two community festivals – the Neighbourhood Futures Festival which we co-host with Birmingham Settlement annually at their Nature and Wellbeing Centre, Ladywood, and the Come to Campus Community Festival which was held in celebration of the University of Birmingham’s 125th anniversary at our Edgbaston Campus. Both were inclusive, free events open to all.

We took these opportunities to engage in a listening exercise with a wide range of participants, talking with over 250 individuals about their own definitions of urban wellbeing, their most pressing concerns, what they value in the places where they live, and how they think community research could play a role in the futures of their neighbourhoods. Here’s a summary of what they shared.

What do ‘urban wellbeing inequalities’ mean to you?

People described how shortcomings in urban services, green access and everyday conditions were produced by unequal resource distribution, transport exclusion, and institutional discrimination. Respondents emphasised that postcode lotteries, wealth concentration and systemic bias shaped who gets to access libraries, health services, affordable food and restorative green space. Our research aims to address these inequalities through identifying the scope for redistributive investment in transport and basic needs, representative planning processes to counter discrimination, and targeted place‑based remedies for noise, crowding and access to nature.

What’s the urban change you most want to see? What needs to stop?

Participants articulated a multi‑dimensional vision of urban change that combines immediate service fixes with structural reforms. At the surface they ask for more youth provision, cleaner and greener spaces, resolved waste systems, improved transport, and housing that serves people rather than markets. Their demands include: equity of access, democratic stewardship, and sustainability. Equity appears in calls for accessible parks and transport, social housing, and the reuse of empty spaces for community benefit.

Democratic stewardship is seen as desirable, through appeals for youth consultation, community action, and representative decision‑making bodies. There was a focus on sustainability through improving transport and housing, seeking emissions reduction, heat mitigation, and resilient materials.

People expressed a desire for clean, safe and green spaces, and were concerned over the longer term about housing and development practices which reproduce market failures, leading to precarity and displacement. Rising transport costs were seen as a source of social exclusion, while perceptions of inadequate maintenance (e.g. of streets and parks) and lack of transparency were seen as eroding institutional trust.

Urban wellbeing interventions should combine regulatory action on housing and development, reinvestment in routine maintenance and waste systems, targeted affordability measures, and participatory stewardship to restore access to dignified urban commons.

What needs to be saved for more positive urban futures?

People want to see a city that is green, inclusive, well-maintained places linked by affordable, low‑carbon mobility and animated by youth and cultural life. Achieving that vision requires coordination across planning, service delivery, and collaborative governance.

Residents want to save urban nature, community places, heritage institutions, public services and the civic values that sustain them. There were calls for protecting trees, parks, biodiversity and pollinators; maintaining libraries, community centres and arts venues; preserving local history; and ensuring cleaner streets and integrated public transport. Underlying these priorities are people’s commitment to empathy, community cohesion and participatory engagement.

What do we need to do to get to and how can community urban wellbeing research help?

To achieve these desired urban futures participants called for collective mobilisation, visionary leadership, and redistributive policy instruments. They wanted to see explicitly anti‑racist approaches, unity and mutual recognition. In the built environments they called for walking and cycling to be prioritised. They wanted to see more mental‑health, addiction supports and care systems.

People were enthused by the potential of community research and proposed easy ways to support this:

- resource community research;

- engage people directly

- ensure engagement is representative;

- produce actionable evidence;

- support community capacity to implement and sustain change.

Key practical recommendations include ring‑fenced funding lines for community‑led research and council support, structured face‑to‑face engagement and avoiding tokenistic consultation. This was seen as the core way to achieve measurable gains in urban wellbeing.