Why research how ethics advice is provided to governments?

There is little existing evidence of who is providing ethics advice to governments, how this advice is organised and most importantly, what its impacts are. When we began planning this research, we therefore needed to provide a basic description of ethics advisory bodies across our national case studies (UK, Australia, Germany). Certainly we found some very helpful case studies and reviews (see Useful Reading below), including some highly insightful recent cases, but this is an ever-changing landscape which needs regular updating.

Our first step then was to do the extensive work of identifying all the ethics advisory bodies and committees that make up national ‘ethics-policy advisory ecosystems’. We name them in this way to capture the sense in which these are organic, dynamic and ever-changing systems characterised by different infrastructural forms, decision-making processes, committee procedures, composition of members and people and social networks.

Our institutional mapping sees the relationships and connections between the institutions to be a key ingredient of the effectiveness of the ecosystems. And one of our core research questions is to find out what works best in what national contexts, for what sectors, and what kinds of policy problems and crisis situations.

Getting to grips with the dark history of ethics advisory bodies

When we hear the view voiced that ‘ethics is everywhere’ or that ‘ethics should be left to ministers and politicians’ or that ‘ethics is only about personal values and professional behaviour’, this can be concerning. Such views can overlook the crucial historical significance of the introduction of formal national ethics committees and advisory bodies.

This history is an essential factor in understanding what the risks are for ignoring ethics advice – the risks of policy failure, unintended consequences, the neglect of legal or moral rights and dignity, a lack of foresight in anticipating scientific, technological and societal changes, impotence in the face of misinformation and declining levels of public trust.

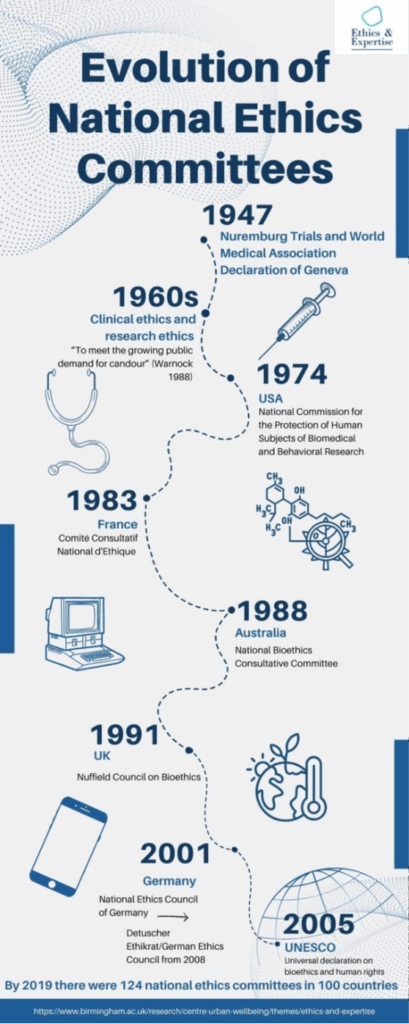

National ethics committees first emerged in Europe following calls from medically focussed institutions. There was a recognised need for new ethics codes associated with the Nuremburg Trials and World Medical Association Declaration of Geneva in 1947. These were in response to the abuses carried out by doctors under the Nazi regime.

Although it is not part of our current research project, the US experience is also notable. The first national bioethics committees in the US in 1974 was a response to the racist horrors of the Tuskegee syphilis trials scandal between 1932 and 1972. These trials had denied treatment to numerous African American men in Alabama for this treatable disease in the name of research. From this historical view, the development of ethics bodies has long reflected key societal concerns about the power of experts, scientific practices and issues of systematic inequity and exploitation.

The international picture: global governance of ethics advice

At an international level, 1985 marked the establishment of the Ad hoc Committee of experts on Bioethics (CAHBI), which led to the first international legislation on the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine in 1999 by the Council of Europe. The Group of Advisors on the Ethical Implications of Biotechnology (GAEIB) was later founded by the European Union in 1991. In 1997 this became known as the European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE) in 1997. These EU advisory groups widened the focus from bioethics to science and technological innovations more widely, under the rubric of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) in the Framework Programmes of the European Commission.

By 2005, the UNESCO Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights recommended that all member states should establish national ethics committees as independent, multidisciplinary and pluralist bodies in order to foster the public debate. At the same time, UNESCO established the Assisting Bioethics Committeesproject, advising at least 14 nations in Africa and Latin America to establish national ethics committees. Its Global Ethics Observatory programme/repository tracks this growing global infrastructure.

More recently, the World Health Organization Global Health Ethics Unit have established specific committees such as the WHO Expert Group on Ethics and Governance of Artificial Intelligence for Health (2019) and the WHO Working Group on Ethics and Covid-19 (2020), now renamed as WHO Expert Group on Ethics and Governance of Infectious Disease Outbreaks and other Emergencies (2023).

One of the key points of current debate in the global bioethics community questions the claims to universality within this field and calls for more diverse perspectives on central issues of justice, whose ethics counts, community and public involvement beyond dominant Western approaches.

In the next part, we’ll provide some institutional maps of ethics advisory organisations to indicate the size and shape of the ethics-policy advisory ecosystems in the UK, Australia and Germany. They can be explored to give researchers an overview of the institutional landscape, and by policy makers who are seeking ethics advice and want to know where and how to start looking, what is already available across this scene.

1 thought on “Ethics-policy advisory ecosystems (Part 1): a potted history”