In Part 1, Jessica Pykett has discussed the history of ethics-policy advisory ecosystems. In the second part, she presents some of our research project’s findings and maps of how advisory systems are organised across Australia, Germany, and the UK.

Draft institutional maps of ethics advice to governments: UK, Germany and Australia

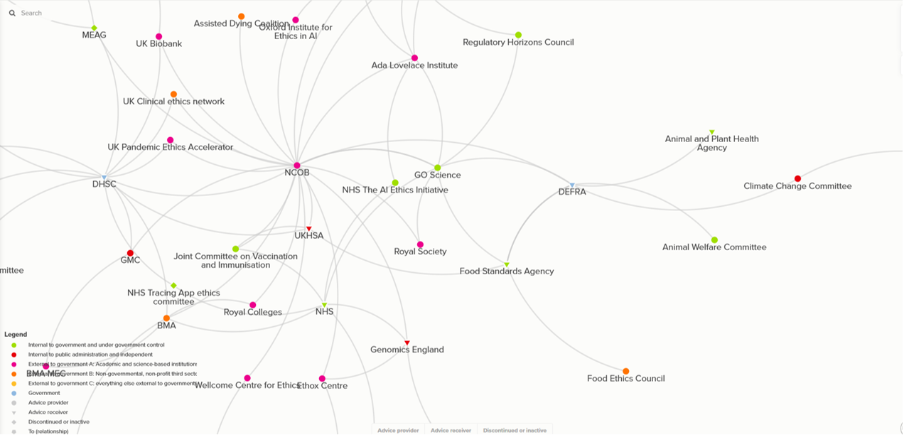

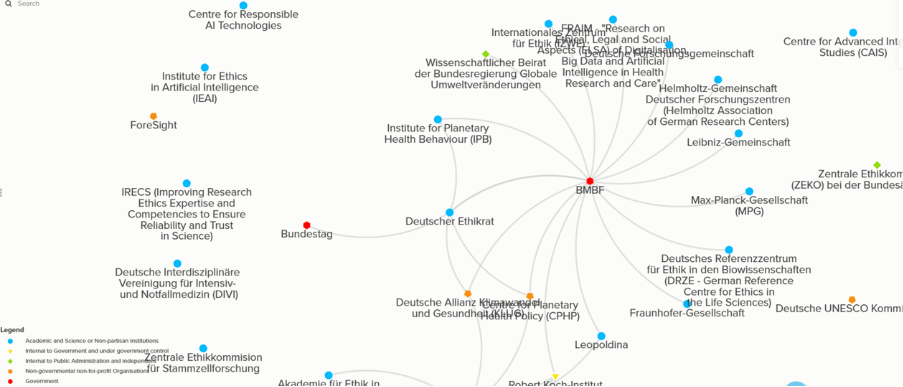

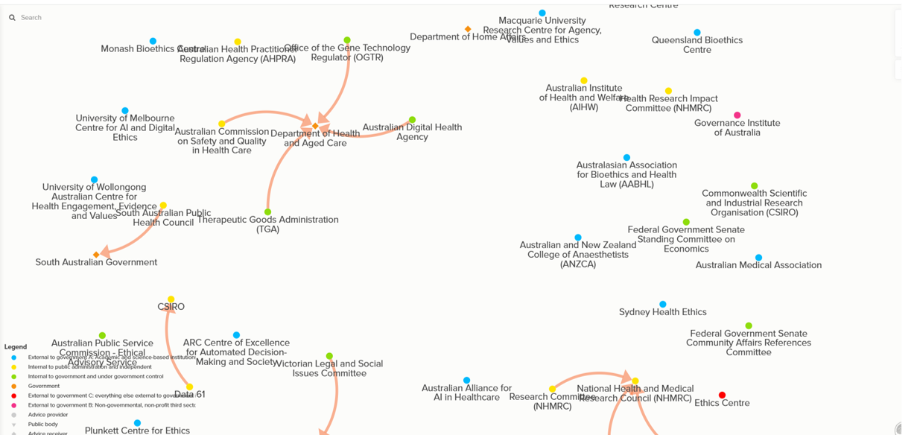

In our current research, we selected national cases which exemplified similar economic and cultural contexts to some degree, but which had distinct cultures of governance – in the UK and Australia broadly a Westminster-style democracy, and in Germany, a more consensus-based democracy. We created a typology of institutions which provide or seek to provide ethics advice to government and mapped the connections between organisations. Based on previous research, we wanted to capture the specific relationship with government. We therefore categorised institutions as internal OR external to government OR public administration and as independent OR under government control.

You can explore the draft maps below. Some important caveats are necessary. These maps are not exhaustive, they are in draft form and we welcome your input on institutions or connections which we may have missed. They are also subject to change – these institutions can come and go at surprisingly rapid pace (these maps were produced in early 2025). You may have ideas on how to better categorise such institutions and what would be the most useful way to visualise these ecosystems for your purposes. If so, do get in touch.

In the UK, ethics committees have long been associated with clinical ethics committees organised locally or through national professional bodies such as the Royal College of Physicians. The Nuffield Council on Bioethics is an independent body which conducts research and policy work on the ethical and wider social issues relating to biomedicine and public health. There remain many other professional ethics committees and boards within public bodies, commissioned by central government departments or within professional societies, agencies and research organisations. Overall the UK’s ecosysten seems to be strongly networked, with some more dispersed institutions.

In Germany, the National Ethics Council of Germany was established in 2001. In 2007 the Ethics Council Act was passed by the Bundestag (Federal Government) which gave this council a new name and a formal mandate to provide ethics opinions to government as the Deutscher Ethikrat (German Ethics Council) in 2008. Academic and Scientific bodies play an important role in developing ethics knowledge and many are highly integrated with government. There are a large number of regional medical ethics committees associated with university hospitals, which are not the central focus of our inquiry. Overall the picture in Germany is more centralised.

In Australia, there is no central national ethics committee. There are, however, some state/territory-level ethics bodies, several professional medical bodies and a national committee covering ethics in health research. In our research we found a common role for consultants in ethics advice here. In 2024, an independent not-for-profit organisation, The Ethics Centre along with University of New South Wales and University of Sydney made an economic case calling for national government funding to establish an Australian Institute for Applied Ethics. In Australia then, the ecosystem appears highly dispersed.

In our future research, it will be essential to go beyond this ‘most similar cases’ method to understand highly contrasting government regimes and changing processes of democratisation and de-democratisation. We are currently investigating the national factors which shape the effects and effectiveness of ethics advice to governments, and developing criteria for evaluating how these ecosystems work in practice.