This #GlobalEthicsDay, we’ve been reflecting at the ESRC “Ethics and Expertise” policy roundtable with UK experts on how science, policy and ethics intersect.

We wanted to find out more about whether ‘ethics expertise’ and ‘ethics training’ are needed or wanted as part of the professional capabilities of civil servants, what kinds of forms this might take, and what missteps to avoid along the way.

There’s currently a gap in research on how ethics is used in policy-making processes, and it is sometimes dismissed as a tick-box exercise.

We think that embedding ethics could potentially help civil servants to feel more confident in decision-making, advice and analysing data and evidence, especially where there are clear public concerns, trade-offs and implicit values at play.

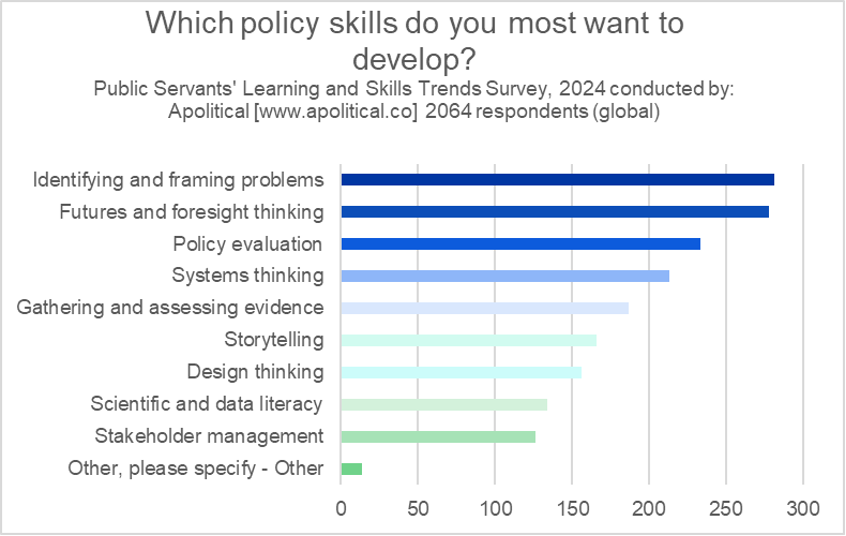

Ethics is one of several thinking and reasoning approaches which improve foresight, framing of policy problems, assessing evidence and evaluating policies, all of which are highly sought policy skills.

Key messages from our expert advisors:

- Civil servants are time-pressed and deal every day with complex problems, diverse sources of knowledge and participate in a complicated advisory landscape, so we need to be clear how thinking about ethics is going to help them.

- The language of ‘ethics’ might be off-putting, as most people associate this with professional standards, codes of conduct and personal integrity, or see this as the responsibility of ministers and politicians, so we need to define ethics and show how it contributes to good governance.

- There is value in supporting civil servants to develop ethical literacy or capabilities – this could include making assumptions more explicit, understanding how values intersect with diverse forms of evidence at every stage (from producing, evaluating, using evidence), knowing how and when to consult with ethics experts, navigate emotive issues and navigate sometimes polarised public opinion.

- Academic experts need to work with humility in advising policy makers, understanding the remit, scope and limitations of their advice, and their own value assumptions and integrity in presenting evidence.

- The best routes to embedding ethics in UK policy making are to work with established learning and development schemes, bring in skilled facilitators, tailor learning to career stage, co-design processes, make learning relevant, intuitive, timely, action-oriented and experiential.

The Civil Service code requires staff to act with 1. Integrity, 2. Honesty, 3. Objectivity and 4. Impartiality. For these people and the wider group of public servants and appointees there is an expectation they will act within the seven Nolan principles. These principles add Selflessness, Accountability, Openness and Leadership to the civil service code of four while also dropping the impartiality expectation. When it comes to developing an awareness of these ethical principles in day to day practice that is left to the staff themselves with the help of senior staff in ethics advisory roles. This approach different from what is found in universities where each scholarly body has its own ethics code and the advice and checking is done through ethics committees and associated approvals processes, at least for research. The processes of advising, developing and checking are less obvious in teaching, assessment and business, community or policy engagement. The U.K. Research Integrity Organisation (UKRIO) provides advice on research integrity and ethics procedures and it’s guidance and workshops might be helpful to people engaged in policy work. https://ukrio.org/