Yassin Boudriq (University Mohammed V of Rabat)

The world exists like a tapestry of culture and traditions. In some places the unique pieces of cloth are chaotically interwoven with each other, in others the original pattern is kept more neatly. Nonetheless, there is hardly any piece that remains completely untouched – free from interaction with the others. The question of which pattern belongs to whom becomes more complex with the mobility and exchanges of our current day and age. With this, the locality of heritage also shifts. The questions linger… does heritage belong to a place? Does it belong to a thing? Does it belong to people? And if so, who does it belong to?

Intangible heritage has the power to transcend the boundaries of both space and time. Festivals, medicinal practices, food, dances and musical performances can be spread far and wide. All the while they carry the soul of the culture and context it was once born out of. With its power, intangible heritage can be the thread in between the pieces of the tapestry – it can teach, bring together and strengthen the solidarity. It can help blend, find space and facilitate the coexistence of different patterns. However, intangible heritage can also be the exclusive pattern for a specific cloth. It can be claimed, protected and set apart. For with all the weaving and sewing, there comes the danger of appropriation. Intangible heritage thus presents a very fine line of tension from which to investigate the blurry confines of culture, knowledge and the groups that carry it.

In this entry, we travel from Leiden, where the entire town is turned upside down in October to celebrate freedom from the Spaniards almost 450 years ago, to the world of African cuisine at the reach of people in The Netherlands. Then we go to Morocco, especially to Imilchil a high atlas village where a traditional festival is celebrated every year in September. During this event the cultural heritage of the tribe of Ait Hadiddou is presented to tourists and other outsiders. We finally arrive in Brazil in order to find and hear the voices of indigenous people in the Brazilian Amazon about bioeconomy and what is their perception on the use of their intangible knowledge in this new worldwide spread idea of economy.

We hope you enjoy the trip!

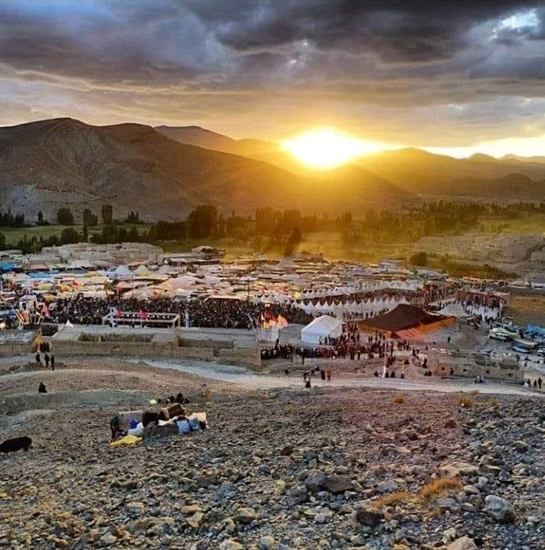

Imilchil, a Moroccan high atlas village situated in the southern east of Morocco, is known by his annual festival organized every last week of September. In last decades, the festival was mobilized to attract tourists. This mobilization gave birth to a conflict between touristic actors (hotelkeepers and tour-guides) of the village, and other inhabitants who comments on the consequences of it. In this blog, we will see how those inhabitants express their viewpoint about the mobilization of their festival in tourism.

In Morocco, tourism is one of the most important source of income. This industry is a pillar in the socioeconomic development of the country. In last decades, tourism gained a considerable momentum, the number of tourists was augmenting and the number of local population involved in the industry expended. One of the factors that attract tourists to visit Morocco is the rich cultural heritage of the country. Therefore, touristic actors are more and more interested in the mobilization of it, it represent a key element in their practices (hotel keeping, tour guiding, artifact manufacturing). Nevertheless, the mobilization of the cultural heritage in tourism is not always essay to do, because it is does not belong only to touristic actors, rather it is a common immaterial wealth. Thus, in this blog, I propose to discuss how the mobilization of cultural heritage in touristic areas can cause conflict between theirs inhabitants. Moreover, the most important question is: how the inhabitants reacts to the mobilization of their heritage by touristic actors?

I choose to focus on the case of an annual festival celebrated in Imilchil, a Moroccan high atlas village that belongs to the Ait Hadiddou tribe. The choice of Imilchil is made for one reason. It is my natal village, and this idea of researching about it represents an opportunity to discover my origins, because I was born in this village but I grew up in another city (Meknes). Before analyzing the mobilization of the festival in tourism, and how the population of the village responds to it, I want to present the method of research I adopted. The festival is always celebrated every year in last week of September. Since I did not have the chance to observe it directly, I choose to do a virtual ethnography. I started to visit the Facebook pages talking about the festival, especially the blogs published during it celebration. I focused on the blogs that comments on the consequences of its mobilization in tourism. This virtual ethnography is important because the social Medias, particularly Facebook, gave the local population the opportunity to express their viewpoint about such matters. The platform is used by young educated inhabitants who present the negative consequences of the mobilization of the festival in tourism. These blogs were written in classic Arabic, which means that the bloggers speaks with the visitors of the event.

One of the most remarkable things about the festival is that it has two names. Touristic actors of the village use the name “festival des fiançailles”, while the local population use “Agdoud” which means a gathering of people. This is not just a differentiation of names, but it is a differentiation of perceptions too. For the outsiders, the festival is known by its first name, or its Arabic translation “mawssim, al-khotouba”. The choice of it is based on the collective marriage celebrated during the festival. Thus, on the third day of the celebration, several young men and women celebrate their marriage in the central place of the event. Moreover, other touristic actors argue that the event is an opportunity for young men to find a wife during the festival, because they are allowed to meet and discuss during the event, without the surveillance of their parents. Therefore. The festival is presented to tourists as one of the important traditions of the Ait Hadiddou tribe, an event that shows the collectives marriages and the traditions relevant to the social and cultural status of women, especially the freedom given to her during the festival to choose her husband. The touristic actors present to tourists the image of an event where young people meet to get married. However, how the other inhabitants sees this mobilization, and how they react to the image that those actors give to outsiders?

The first thing the inhabitants criticize is the falsification of the name of the event. According to them, the touristic actors should respect the traditional name of the festival that is “Agdoud N-Qulmghani“. The mobilization of the event in tourism caused a change of his name. For example, Aziz wrote a blog about this falsification, he said: “festival Ali Ben-Amrou in Talssint, festival Moulay Abdallah Amghar in Al-Jadida, these are real names since the beginning of these festivals, their names were not being alternated to attract tourists… why the falsification of the real name of the event from Agdoud N-Oulmghani to festival des fiançailles?”. Consequently, the inhabitants wonder if the preservation of traditions is the main concern of those actors, because of how to explain that the people who pretend to protect the cultural heritage of the tribe, change the traditional name of the festival. Most inhabitants highlighted that touristic actors care less about cultural heritage of Ait Hadiddow; they care more about gaining money. The name “mawssim al khotouba” and the image of an event where anyone can get married to a young woman attract tourists. According to one of the hotelkeepers, tourists came to the village because of the name “festival des fiançailles“, no one could care about the name “Agdoud N-Oulmghani“.

The other point that the inhabitants criticize via their blogs is the image that those actors present to tourists. They consider that touristic actors give the tourist an image of a “primitive” tribe and people, because the inhabitants confronted the accusations of “selling their daughters in the festival”. The inhabitants think that when tourists came to the festival they misunderstand the traditions of the tribe; they consider the event as a market where any male can “buy” a woman to marry her. Thus, the media focuses only on the collective marriages and give the image of a market where women are for “sale”, this can explain why most Facebook blogs of the inhabitants repeatedly quoting: “our women/ daughters are not for sale“. Abdallah said about this: “Agdoud is an event where the Ait Ḥadiddou get together with other tribes. It is a big event organized to exchange goods, but unfortunately, the Media along with the touristic actors present a false image about it”. The touristic actors are accused to spread this image because they use the same name used by the media, and because they do not try to change this image by correcting it for tourists. As a category dealing with the outsiders, the touristic actors of the village were accused of circulating a false image about the tribe to the tourists.

We can see that the example of this festival gives us an idea about how the mobilization of the cultural heritage was a cause of conflict between touristic actors and the other inhabitants. The first ones had the power of presenting the tribe image to tourists, they tried to invest in the festival as a pillar of cultural heritage of the tribe, but the young inhabitants used Facebook to criticize the consequences of this mobilization. In this conflict three things an articulated: 1) a self-image that is being presented to others; 2) power relationships between tourists, touristic actors and the inhabitants of the village; and last but not least 3) a sense of well-being on the side of the inhabitants that claims that their reputation was damaged by the false image presented by touristic actors. Adi resumed this whole dynamic in his blog, he said: “I will not be able to express how an image about Agdoud was circulating in Media, nor be able to justify how in the autumn of 2004 the name festival des fiançailles altered the original one Agdoud. How can I express the scene of many visitors that came to Agdoud with the fantasy of a “market to sale women”. How they [the visitors] can understand the history of the tribe, while they are under the spell of a false image presented by the Media?”

This blog is part of the Group Intangible Heritage blogs.

Voices that are not being heard when we talk about bioeconomy

About the author

Yassin Boudriq is a PhD student in anthropology at l’Institut Universitaire des Etudes Africaines, Euro-méditerranéennes et Ibéro-Américaines of the University Mohamed V of Rabat, Morocco.

Join the discussion

1 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments