Hind Bouqartacha (University Mohammed V of Rabat), Liesbeth Nonkululeko Kanis (Leiden University), Simone Pfeifer (University of Cologne)

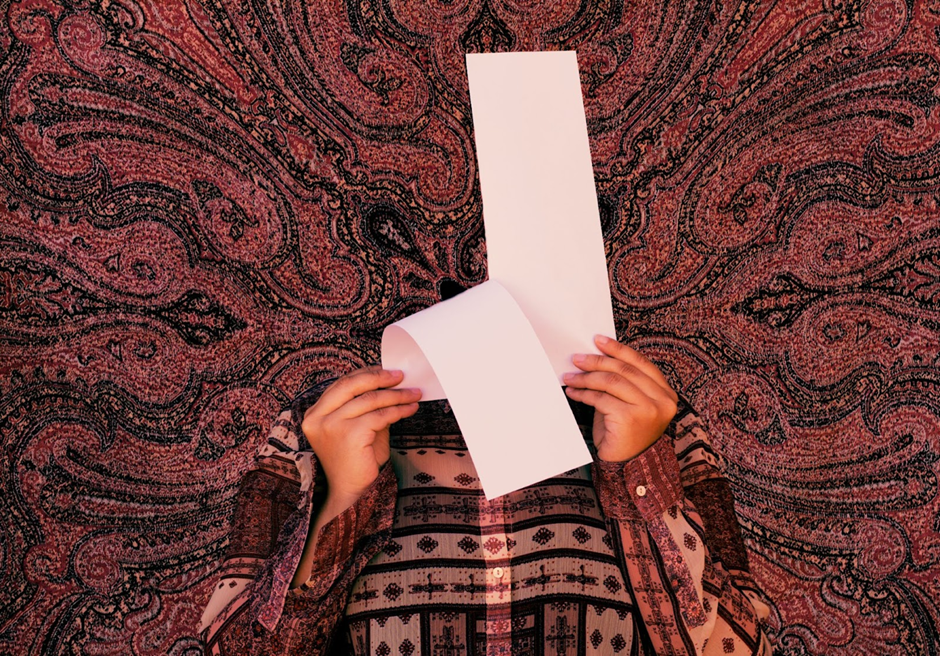

“I took this self-portrait during challenging times of my life. As I look at it now, I can still vividly recall the emotions that compelled me to take it. At that time, I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere, like I was always an outsider looking in. I felt like my differences were too apparent, too conspicuous, and that they set me apart from everyone else. As I was hiding half of my face behind the sheet of paper, it’s almost as if I’m trying to erase a part of myself, to make myself more like the rest… while the other half of it is blended into the background, trying to disappear entirely…”

Introduction

This self-portrait expresses the themes of identity, in/visibility, voice and marginalisation addressed in this blogpost. Like the patterns and threads in the background that merge with the clothing, we are weaving together stories from different localities that explore the connection between well-being and employment through an intersectional lens. As in the self-portrait, there are many layers that make up one’s identity and they often overlap, or intersect, yet aren’t always clearly visible, (made) known or voiced, but nonetheless can have a tremendous impact on everyday life.

The three narratives below partially unfold and voice these, so the reader and listener get a glimpse of people and their lived experiences. Lived experiences are key in our understanding of the world and by sharing these we increase our understanding of what role intersectionality, such as gender, sexuality, nationality, ethnicity, and religion, plays in employment and how it impacts well-being.

Narrative threads from different localities

You are invited to first listen to or read the narrative threads from different localities (Morocco, The Netherlands and Germany). We conducted informal conversations in English, German and Arabic and would like to gratefully acknowledge those who consented to participate. The second part of our blog contains observations and preliminary analysis of our findings as part of the VOICE project we conducted for EUniWell.

[1] Tales of Identity and

Self-Expression in the Workplace (by Hind Bouqartacha)

[2] Ultimate Well-being: Serving as a Ladder to Help Fulfil People’s Needs (by Liesbeth Nonkululeko Kanis)

[3] ”Just because I wear the hijiab“ (by Simone Pfeifer)

Perceptions of Well-being

Perceptions of well-being are multi-layered and complex, as Amy in narrative [2] points out. For Amy well-being is not just physical or mental but encompasses a whole range of dimensions that are also largely subjective. Amina in [1] attributes her well-being to the ability to freely express her Amazigh identity in her workplace. She calls herself “lucky enough”, as opposed to her colleague who hides her identity. Li-fan in [2] equally feels “fruitful and lucky”, reporting an increase in his overall well-being in relation to employment. In contrast, Maryam, Sarah and Dilek [3], report instances of discriminatory experiences because of wearing a visible religious identity marker, a hijab, which in turn, greatly impacts their sense of well-being. These examples remind us of the complex and varied experiences and the need for nuanced understandings of intersectional forms of discrimination where gender, religion, age, ethnicity, nationality, socio-economic, status and many other intersections relate in particular ways to the experiences of well-being.

“Human beings are complicated, and so is also the well-being of them.” (Amy [2])

Employment and Well-being

“Self-fulfilment” and “contributing to something meaningful” are mentioned as higher goals by young professionals in [2] directly linking employment to their sense of well-being in society. In [3], Dilek relates it to a balance with motherhood. Painful experiences at work in return greatly impact well-being in a negative sense, as we can see in Amy’s case [2] and in the individual stories of Maryam, Sarah and Dilek in [3]. In the latter case, rude and insulting behaviour in the workplace related to wearing the hijab, results in a feeling of not being accepted professionally, as well as being judged as a person solely on outer appearance. The example in [1] points to the fact that hiding one’s identity due to negative stereotypes and discrimination can also have a negative effect on well-being. It can create a sense of disconnect from one’s true self and lead to feelings of shame, guilt, and anxiety. And can contribute to a sense of isolation and social exclusion. As we glean from the different stories employment and well-being relate in multi-layered and complicated ways and are not always experienced in a one-dimensional way.

“They also said quite openly, sorry, we don’t take anyone with a headscarf.” (Maryam [3])

Voice and In/Visibility

The theme of In/Visibility plays a role in the two contrasting experiences of Amina and her co-worker in [1]. Amina had a positive experience and did not face any discrimination due to her Amazigh identity. She believes that being open about her heritage and identity was the reason she avoided discrimination. However, her co-worker, also Amazigh, chose to hide her identity due to perceived negative stereotypes and prejudices. She chose to blend in with her colleagues and married an ethnically Arab man to assimilate to the dominant culture. This highlights the complexity of intersectionality on one’s sense of identity and belonging, where one experienced freedom and another discrimination, despite commonalities in gender and ethnicity.

In/Visibility also plays a role in [3], where Maryam and Sarah report negative experiences in their workspace (health care), because of wearing a visible religious identity marker, a hijab, and how this made them negatively stand out. Sarah even experienced being treated in a rude and insulting way by other patients and customers.

The feeling that one’s voice isn’t heard because of one’s background is quite clear in [2], where Amy admits that she “many times felt like a minority” and sometimes felt that her voice was “nipped in the butt”. She even snaps her fingers in front of her, as she links this directly to her background. It shows how the loss of voice can create a sense of disconnect from one’s true self, contributing to a sense of isolation and social exclusion, diminishing well-being.

This again calls for the need for a nuanced understanding of intersectionality and the complex and varied experiences of individuals within marginalized groups.

(Double) Marginalisation

Marginalisation is one thing, but several interviewees in the different localities experienced what one of them dubbed: “double marginalisation”. Even though for each of them this holds a different meaning. The inclusion/exclusion mechanisms play a key role here. Who is including and excluding, and what if the ones who are excluding are the ones you least expect it from due to perceived shared commonalities in lived experiences or similar perceived identity.

In [2] Amy uses gestures and body language to express the discrimination and sense of marginalisation she experienced in a rather vivid way. Striking is that she admits to having felt most marginalised in the workplace by another migrant, where one would expect a shared commonality or solidarity. This is contrary to the perception of double marginalisation that Li-fan brought up in the dinner conversation in [2]. According to him it does not impact his sense of well-being nor makes him feel marginalised himself, because of his employment. This also came out in [3], when Sarah shares the story of her sister who was denied a job in a very diverse neighbourhood where she expected solidarity and commonality when looking for work.

The Amazigh women in [1] reveal how crucial it is to be able to express one’s identity freely without worrying about facing prejudice, which is a key aspect of well-being. It also illustrates how intersectionality works, where people with several marginalised identities may experience aggravation or prejudice, but not all necessarily do so.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the above examples are a reminder of the complex and varied experiences of individuals within marginalised groups, and the need for a nuanced understanding of intersectionality in discussions of discrimination and wellbeing, particularly in relation to employment. Employment and wellbeing relate in multi-layered ways and this relation may also change over time, as the different stories and threads reveal.

About the authors

Hind Bouqartacha is a Moroccan photographer, videographer, studio owner and first-year PhD student in Lettres and Human Sciences at the University Mohammed V of Rabat, Morocco.

Liesbeth Nonkululeko Kanis is a China Studies and LDE African Dynamics graduate from Leiden University who specializes in Africa-China Relations and knowledge production for development. Previously, she worked in international academic publishing in Europe and Asia, and with VSO Tanzania in the capacity of academic publishing and research advisor at St. John’s University of Tanzania in Dodoma.

Simone Pfeifer is a Postdoctoral researcher at the Research Training Group “connecting-excluding”, University of Cologne, Germany. She is a social and cultural anthropologist focusing on visual, digital and media anthropology. In her current work she explores Muslim everyday life and social media practices in postmigrant contexts from a critical and reflexive perspective. In her previous research, she focused on transnational social relationships between Senegal and Germany, securitisation of Islam, political violence, and ethical challenges in ethnographic research.

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?