Meriam Bouzineb (University Mohammed V of Rabat)

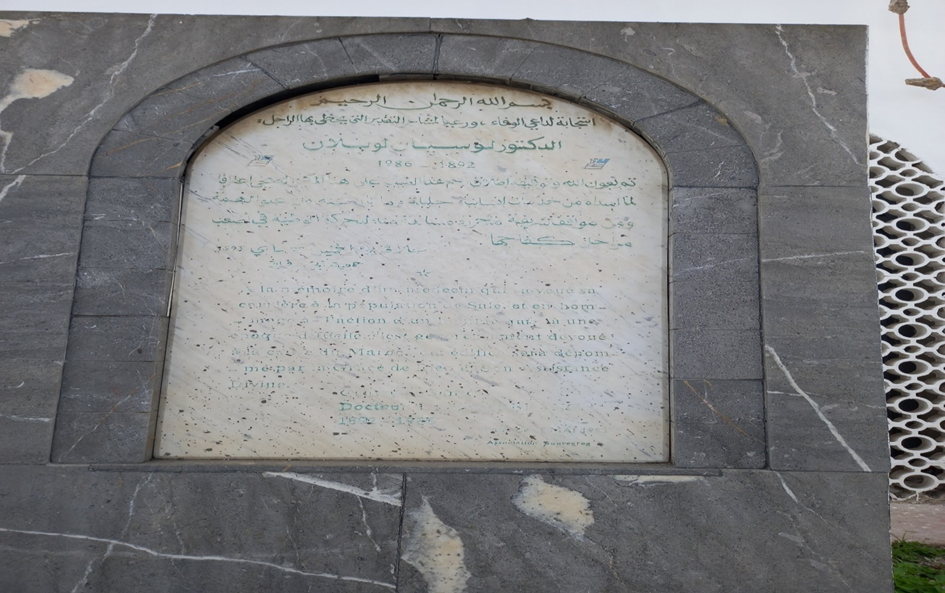

The old medina of Salé is surrounded by a rampart with several old-centuries doors, one of these doors, “Bab El Khemis”, had given its name to the health center of the district. But, when you enter the health center, the first thing you notice is a memorial stone, where, if you had the chance to have gone to school, you can learn that “Bab Khemis” health center’s name is in fact “Lucien Leblanc”, since may 1993. A civil association had renamed it according to a french medical doctor’s name. Do anyone in the neighborhood still remember Lucien Leblanc? Who was he and why that association had renamed the health structure in his memory ?

In october 2017, when I had been proposed to work at the Health Center « Bab Khemis », « Thursday door », I learned, one day I took the time to read the memorial stone at the entery, that this establishment had been renamed « Centre de santé docteur Lucien Leblanc » since 1993. On the occasion of my participation in the Decentring Epistemologies for Global Well-being, around knowledge and well-being theme, in the memorials sub theme, I found it a great opportunity to know more about the name of « Lucien Leblanc » in the memory of the inhabitants in the neighborhood who had lived during the french colonial epoch.

Who is Lucien Leblanc for the inhabitants in the neighborhood of the primary health care facility known « Bab Khemis » by everyone ? From “Bab Khemis” to “Lucien Leblanc”, what motivated the civil association “Bouregreg” to rename this primary care facility, when people living around, the healthcare givers and also the official stamp of the center, still use the arabic name of « Bab khemis » ?

According to my three interwied, born respectively in 1928, 1948 and 1953, having in mind that Morocco got its independance on 1956, « Bla » was an extraordinary doctor who ha his private medical office at the modern district of « Rmel », not far from the old medina of Salé, who had been discribed as a generous doctor who used to offer his services for free to population in need, and who was able to speak arabic with them.

But the core information I could find was from « Les cahiers de Salé, pour une mémoire collective » ‘The notebooks of Salé, for a collective memory’. Doing an internet research, I could find that the name « Lucien Leblanc » had been mentioned in a recent publication, the second volume of « Les cahiers de Salé, pour une mémoire collective », edited by the Fondation de Salé pour la Culture et les Arts ‘Salé Fondation for Culture and Arts’, presented to the public in the mark of that foundation activities.

I hadn’t be able to find these notebooks in libraries, so I contacted the foundation who kindly offered me the two volumes edited untill now. In the second volume, Mohammed Lfakir wrote in arabic about « Lucien Leblanc, and emblematic figure in Salé ».

I could learn that, after practising in several cities of Morocco between 1922 and 1935 (Casablanca, Figuig, Rabat, Khemisset, Sidi Kacem), it was in 1935 that Dr.Lucien Leblanc had been assigned to the Bab Khemis Hospital in Salé, as chief physician, before becoming Director of the Health Bureau for 9 years.

During his practice in the city of Salé, he distinguished himself from other doctors by his solidarity with the inhabitants of Salé and his region during the bloody and painful events that the city experienced on 29 January 1944 on the occasion of the request for independence, when seven martyrs died. The gunshot wounded were taken to Dr. Leblanc’s office, who treated them by removing the bullets from their bodies, without denouncing them, and that’s what he was demissed from office for.

In 1947, he moved as a private doctor to his home in the Rmel district and left Morocco in 1984 for France, where he died on January 3th, 1986.

In recognition of his loyal services and his actions in solidarity with the nationalist movement, in collaboration with the Bouregreg association and the association of pharmacists of Salé, on 1993, may 27th, the Bab Khemis Health Center built in 1937, had been renamed “Doctor Lucien Leblanc’s Health Center, in the presence of his eldest son Jean-Pierre.

During the process of my flash ethnography, I was like shuttling between what I’ve heard from people living in the neighborhood, and what the authors of The Notebooks of Salé had written to keep the memory of their town alive, and where I could read a lot of stories about the colonial and the post colonial epoch.

When I began my field work, the first man I’d interviewed used to live in Salé in the colonial epoch during his youth, he is now ninety-five years old. When I asked him to tell me about what did he remember about the health center, the caregivers…his memory chose to make him talk about the dogs the colonisator unleashed in streets of the district, about the nationalists’ manifestations, about his youth, and how him and his family moved from a house after people warned them that the owner was a betrayer. He also remembered that the health center was first a court of law, with a very fair moroccan judge, who didn’t need more than a chair covered by a prayer carpet , when in reality the court of law was in the building joint.

In « les Cahiers de Salé », I learnt that « Bab Khemis », the « Thursday door », was « before « Bab Fès » or « Fès Door », the door the travellers in their way from Salé to Fès went through. But when a weekly market began to take place on Thursdays in the place outside the door, it became « Bab Khemis », a place where rural and urban communities used to melt.

I could manage an interview with Mr Mohammed Lfakir, the author of the famous article about Lucien Leblanc, and asked him about what motivated him to write about this topic. He wanted me to know that he had been shaped by the « nationalist culture », influenced by his friend and professor Abdellatif Laabi- a well Known Moroccan engaged intellectual- known, according to Mr Lfakir, to like « breaking the mold of language », which means for the intellectual, writing in french but thinking Moroccan. What most made Mr Lfakir write about Lucien Leblanc, is his « social engagement with Moroccans ». He also precised that he had already written about him in “Encyclopédie du Maroc”. But at this stage of my ethnography, my question has shifted: Why there had never been an official signboard with the French name in the health center? Why do popular and institutional memories mismatch?

This blog is part of the Memorials in Context group

Within our subgroup, « memorials », it was all about memories…memories of terrorist attacks in Germany, memories of armed resistance in Kenya, memories of African and Caribbean soldiers in London. We’ve been diving with ghosts in an ocean of memories, in public places, in a museum, in a health center… And we’ve been thinking: What would be linking those memorials together? Which history stays in people’s memories and which events get appropriated by institutions? How do memories get shaped?

Memory is a concept that allows one to create and hold a narrative of a moment or an event in the past. Each day we are presented with memory and tasked with how we want to carry it forward, in our history books, in the news, in our streets and within our personal lives. On an institutional level, those memories can often be determined and shaped for us by government or specific groups. But are they ever an accurate representation for those affected who have lost and cannot speak for themselves? We are faced with the question of who gets to tell one’s story and how, or who’s story is told and what conflict does it create? We find ourselves In an ocean of memories, where our future decisions are shaped by the lessons we learn from past events that have become memories, challenging us to understand how institutions shape our view and perspective of the past.

Memorials are found in various places, whether the physical locations of events, on houses or buildings, central spaces of cities or in remote places on the margins of social life. Monuments come in different forms and are sometimes more, sometimes less visible or recognisable as such. Their common feature is that they refer to a past that is worth remembering – or is or has been deemed to do so. Memorials are in some cases meant to remind us of our past while deepening our knowledge of how we relate with the future. Memorials, similar to other forms of institutionalized cultural memory, are intended to exist in perpetuity and thus point towards the future. However, social valuations are not constant at all, which is why memorials (from their emergence to their end of life) are always places of social and public debate, which also offer potential for conflict.

As part of our Global Classroom, we, Joseph, Meriam, and Fabian engaged with various memorials in Nairobi (Kenya), Rabat (Morocco), and Cologne (Germany). Here we describe our impressions and the process of our individual and collective engagement in separate articles.

The memorials we deal with have a wide thematic, aesthetic, pedagogical and historical range and could not be more different. The purpose of their existence also varies in the different contexts and cities we live in. In the course of our joint research and learning, we exchanged views on similarities and differences and thought about how we can nevertheless relate the different monuments, their local settings and meaning as well as our individual approach. The comparison and joint reflection during our exchange was of vital importance in order to get a sharper view of the site-specific context, implicit and explicit meanings as well as controversies developing around or emerging from the monuments.

In this process we encountered memory sites which deal with an artificial tree in the National Museum of Kenya remembering the Mau-Mau resistance (Joseph), the renaming of a healthcare facility in memory of doctor from the French colonial epoch (Meriam), and non-existent memorials for the victims of right extremist violence in Germany/Cologne (Fabian). A common thread of the three topics and the local issues that emerge around them is a matter of memory upon the table of social negotiation. Public memory in terms of representation, participation and being recognised and making oneself recognised as a full part of society is linked to the question of social well-Being, a concept we have to take up and at the same time deconstruct in our prismic perspective on the making of public memory.

Memory without Memorials in Germany

About the author

Meriam Bouzineb has been working as a medical general practitioner since 2002, first in rural areas and then urban ones from 2016. She could notice that she had a lot to learn about humans, since the knowledge she had been taught at the faculty of medicine was almost about illness, and that didn’t help so much when most of time she had to deal with socioeconomic issues. In 2015, she didn’t hesitate when she had the opportunity to do a bachelor’s in social sciences. She is now a PhD student at the University Mohammed V of Rabat, doing research about primary healthcare practitioners between their reality on the field and health policies’ requirements.

Join the discussion

1 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments