Lifting Limits is “a social enterprise with a mission to challenge gender stereotypes and promote gender equality in and through education”. In this blog, Caren Gestetner from ‘Lifting Limits‘ shares her vision and discusses how and why we can and should challenge gender stereotypes in school environment.

Caren Gestetner left a career in law to pursue her interest in gender through a masters degree in Gender, Policy and Inequalities at the LSE. Caren wrote her dissertation in the field of gender in education and her studies, together with subsequent work in schools and the experiences of her then primary-age children, convinced Caren that many gendered inequalities seen throughout society can be traced back to how children learn society’s gendered expectations from a young age.

Caren co-founded Lifting Limits with a mission to challenge gender stereotyping and promote gender equality, in and through education. Lifting Limits is currently running a year long pilot testing its whole school, evidence-based, approach in 5 London primary schools. To find out more visit http://www.liftinglimits.org.uk

***

‘Pink is a girls’ colour and blue is a boys’ colour’, my daughter told me on the way home from nursery one day around the age of 4. I was not only taken aback by what she said but also horrified at the way she asserted this statement as a matter of irrefutable fact. At this juncture we as adults have a choice – to either ignore and accept or to challenge and discuss. If we take the former route, we implicitly reinforce the gendered status quo and this is what children learn as ‘the way the world is’. Of course colour is not the most important example, but messages young children pick up about who makes a scientist or a carer, what it means to be ‘bossy’ or ‘ladylike’, to ‘man up’ or to ‘cry like a girl’, can have profound effects later in life – feeding into children’s future relationships, subject choices, career path, workplace behaviour, engagement in the public sphere and even health outcomes. The seeds for many gender unequal outcomes which persist in the private and public spheres are sown in the gendered stereotyping which surrounds children from birth.

There is a growing awareness of ways in which gender stereotyping in a number of areas channels girls and boys down different paths, for example through toy marketing and gendered messages in children’s clothing (see also Marianne Cronin’s blog for GLARE). But what about the influences children encounter at school – are we safe to assume that school is an environment in which children of all genders are treated as equally capable?

Schools

Starting from a school’s statutory equalities policy, one would assume so – wording typically draws on equalities legislation to reassure that all learners are of equal value and will be protected from discrimination on grounds of sex (amongst other characteristics protected under the Equality Act 2010). Yet dig a little deeper and we find that even the best school and the most well-intentioned staff may be inadvertently perpetuating gendered stereotypes and messages. I’m talking about daily practices and interactions which happen ‘below the radar’ without any deliberate sexist intent. My work with Lifting Limits takes me into many schools and the messages I pick up on gender equality are mixed ones – although children are told explicitly that girls and boys are equal and can do anything in life, that message is not consistently reflected in what children see and hear in their school environments. I shall draw on examples from three areas to illustrate: books, language and curriculum.

Books

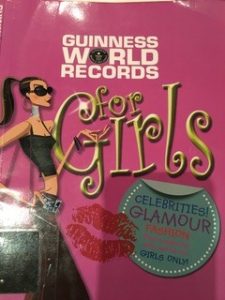

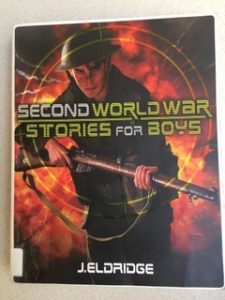

Whilst many schools make an effort to source books from a growing selection specifically modelling equality and diversity, books in schools do still largely reflect the mainstream book market which remains gendered in how it both presents and markets children’s books. A 2017 review by the Observer of the top 100 children’s picture books found lead characters twice as likely to be male and male characters 50% more likely to have a speaking part. 73% of creatures given a gender were male – and they were more likely to be wild dangerous creatures whereas the female creatures were generally small and fluffy. Villains were 8 times more likely to be male than female. The findings of this study resonate with what we see in school libraries and classroom book corners – boys having adventures (often with a female sidekick), mums holding the fort at home, a minority of animal characters as female and clearly marked out as such through exaggerated eyelashes and lips. When it comes to non-fiction we find men dominate biographical works and books covering exploration, science or invention. The findings of a 2018 study of science books for children in a number of public libraries showed women to be significantly under-represented: overall, children’s science books pictured males three times more often than females, reinforcing the stereotype of science as a male pursuit – and under-representation of women gets worse as the target age of the book increases.

Language

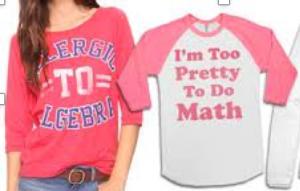

Language does not have to be deliberately sexist to send gendered messages of suitable roles and behaviours for women and men, the unconscious bias we all have can be enough. It can be with the best intention that an adult might say to a girl ‘I love your dress, don’t you look pretty today’ – harmless in itself but combined with the multitude of messages girls see and hear such as slogans on t-shirts (‘I’m too pretty to do math’) and unrealistic ideals of female beauty portrayed in the media, suggesting a value attached to female looks above other attributes. Language can do many things: demean or trivialise (‘girls’ used to refer to professional women); exclude (‘mankind’, ‘fireman’); assume roles (‘lady doctor’, ‘did daddy fix it for you?’) or characteristics (‘I need some big strong boys to move these tables’). Language can also suggest unhealthy norms of masculinity, that boys should not show their emotions (‘man up’, ‘you cry like a girl’), other than through anger, or can’t help themselves in bad behaviours (‘boys will be boys’). As in wider society, children hear language used in all these ways in schools.

Language does not have to be deliberately sexist to send gendered messages of suitable roles and behaviours for women and men, the unconscious bias we all have can be enough. It can be with the best intention that an adult might say to a girl ‘I love your dress, don’t you look pretty today’ – harmless in itself but combined with the multitude of messages girls see and hear such as slogans on t-shirts (‘I’m too pretty to do math’) and unrealistic ideals of female beauty portrayed in the media, suggesting a value attached to female looks above other attributes. Language can do many things: demean or trivialise (‘girls’ used to refer to professional women); exclude (‘mankind’, ‘fireman’); assume roles (‘lady doctor’, ‘did daddy fix it for you?’) or characteristics (‘I need some big strong boys to move these tables’). Language can also suggest unhealthy norms of masculinity, that boys should not show their emotions (‘man up’, ‘you cry like a girl’), other than through anger, or can’t help themselves in bad behaviours (‘boys will be boys’). As in wider society, children hear language used in all these ways in schools.

Curriculum

Men have historically dominated many fields and this is (understandably) reflected in who is taught in those fields across curriculum subjects. Even where schools do make efforts to include notable women in given fields, men (and predominantly white men) still dominate the curriculum across subjects and across year groups, sending powerful messages to children about who is an explorer, inventor, scientist, artist or composer. From our school visits and analysis of school curriculum planning, those commonly taught across many fields are predominantly male as these examples show (female names in underlined):

Inventors: Hans Lippershey, Baron Karl von Drais, Edison, George Eastman, J. Presper Eckert & John Mauchly, Alexander Graham Bell, Wilbur & Orville Wright, Martin Cooper

Explorers: Christopher Columbus, Neil Armstrong, Edmund Hillary, Tenzing Norgay, Howard Carter

Artists: Bruegel, Lowry, Arcimboldo, Wren, Rousseau, Picasso, Manet, Matisse, Hockney, Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Haring, Klimt

Composers: Handel, Vivaldi, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, John Williams, Lili Boulanger.

Where women are absent from curriculum teaching their contributions are rendered invisible – and where their absence is not brought into the open for discussion the discrimination behind it remains unchallenged.

Changing the message in schools – and through education

Gender stereotyping is bad for everyone – girls and boys, men and women, wider society – and gendered norms become embedded early, by about the age of 7. Much good work to tackle a range of issues later in life – from the gender pay gap and under-representation of women in engineering to preventing and dealing with the consequences of domestic violence and male suicide – struggles to undo messages learned young about appropriate norms of masculinity and femininity and appropriate gender roles and behaviours.

That is why at Lifting Limits we tackle gender norms in primary school, aiming to head them off before their limiting effects take hold. We take a whole school approach, working with schools to examine their ethos, routines, practices and curriculum, with two aims. First, to bring a ‘gender lens’ into staff practice, interactions with children and curriculum planning so that gender stereotypes are not inadvertently reinforced in the school environment. Second, to ensure that staff, children and parents gain the confidence and tools to identify and challenge gender stereotyping wherever they encounter it – and to distinguish stereotypes such as ‘pink is a girls’ colour’ from fact.

Our externally evaluated pilot, testing our approach and resources in 5 London primary schools, runs throughout the current academic year and we look forward to sharing the outcomes next summer. We are confident that harmful gender messages children learn as ‘normal’ can be changed and that this change has a powerful part to play in improving gender equality across a range of outcomes in schools, workplaces and across society.

Please cite this blog as follows: Gestetner, C. (2019, 28 January). Lifting Limits for GLARE [Blog post]. Retrieved from: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/glareproject/2019/01/28/lifting-limits-for-glare/