Katharine Forbes has written the following post describing the work she did as part of the School’s Professional Skills Module. This module is an option which gives our students the chance to do work placements and build employability while using their skills as historians too.

Founded in 1903 by the Quaker sweets magnates George Cadbury and J.W. Rowntree, the Woodbrooke Quaker Study Centre is a combination of bed-and-breakfast, heritage centre, and institution of religious education. That makes it a pretty diverse and unique place to work. Although Woodbrooke is just around the corner in Selly Oak, it is also the centre of a global community. As one student wrote in 1938, “here are students from almost every part of the world.” For a historian, it’s a treasure-trove of twentieth-century global history.

Last year, I worked at Woodbrooke as part of the Professional Skills module. I wanted to see how the skills I have learned as an undergraduate historian could be applied in the world beyond campus, and to develop new ones that will boost my employability later on. As it turned out, my historical training certainly came in handy when, at the urging of one former student, I set out to trace the history of the centre’s African visitors.

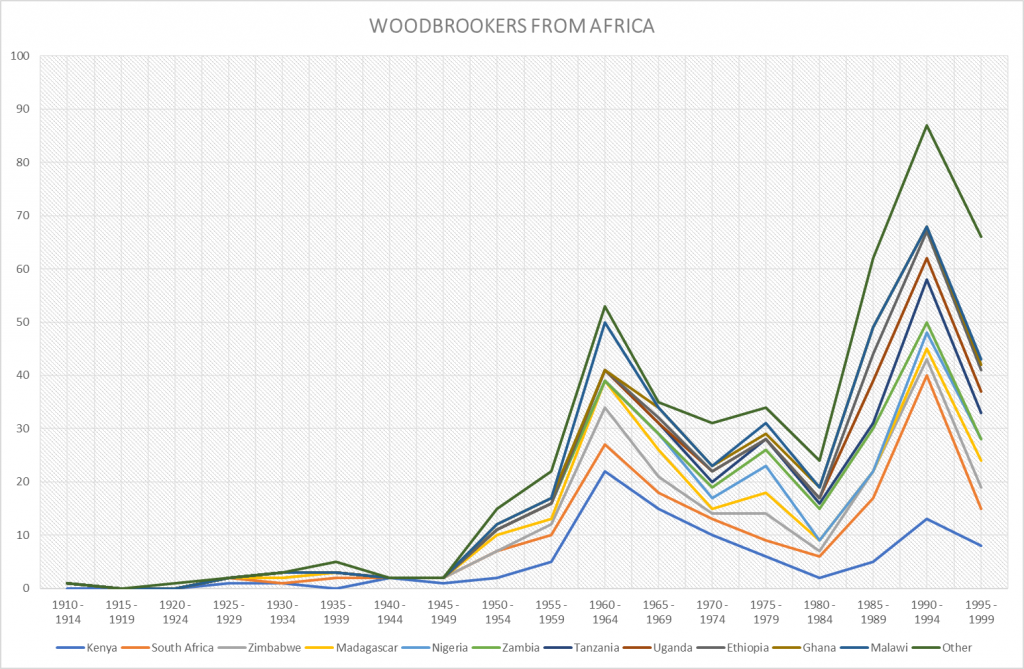

My analysis of the places of origin for hundreds of African Woodbrookers is summarised in the graph [above]. You can see that Kenya, which now has the largest Quaker population in the world, sent more students to Woodbrooke than any other African country. In fact, Johnstone Kenyatta was a resident at Woodbrooke for a couple of terms in 1931-1932. Just over thirty years later, Kenyatta went on to become the first president of an independent Republic of Kenya.

There are clear peaks in African student numbers in the 1960s, when national independence movements were shaking off colonial rule, and in the early 1990s, when Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress were winning the campaign to defeat apartheid in South Africa. Did Quaker ideals make their way into African freedom struggles, via Birmingham and Woodbrooke?

Meanwhile, there was a low-point for African students durign the early 1980s, at a time when Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher supported the apartheid South African regime and called Mandela’s ANC “terrorists.” The big picture of history thus plays out in the records of Woodbrooke’s African students.

Working at Woodbrooke was challenging, but it was also richly rewarding and enjoyable. I honed the skills that I have learned as a historian, to analyse, present, and interpret data—and had the opportunity to apply them to something more long-lasting than my next exam or classroom presentation. My project has helped shine a light on the diversity of the centre’s history, laid groundwork for future research, and helped preserve an important part of Birmingham’s global heritage.