Trigger Warning: homophobia, transphobia, violence, mental health issues

The advent of LGBTQIA+ history month entails a mixed bag of emotions for many; though an essential and uplifting opportunity to celebrate the achievements and contributions of queer people throughout history, it also prompts a sober reflection on the casualties of the struggle for liberation, and the perpetual struggles and prejudices encountered across the spectrum of LGBTQIA+ identities.

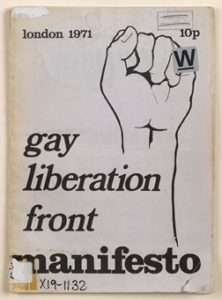

2021 in particular is a year to reflect on the relativity of progress, marking half a century since the publication of the Gay Liberation Front manifesto. Founded by students Bob Mellors and Aubrey Waltor in 1970, the GLF sought a “new sexual democracy about homophobia, racism and class privilege”, in the words of prominent activist, and later politician, Peter Tatchell. The movement was fundamentally the first organised network of LGBT activists that united under the impulse of gay liberation, despite the diversity of members’ identities, political sympathies, and socioeconomic circumstances.

The manifesto packs a punch. Citing foci of conflict and discrimination such as the family, school, the media and psychiatry among others, it calls not just for legislative reform, but a “revolutionary change in society”, attacking not only practical barriers to success, but the inherent injustice which threatened their members on every level and compromised their safety. It lists nine demands to deconstruct this innate socio-political circumstance. With their radical approach to gender identity and their intersectional approach to racism, imperialism and class privilege, it is perhaps hard for some to believe that the document is fifty years old this year, as it reads as fresh and contemporary as ever.

But this is where the issue lies: the manifesto’s continued resonance highlights the continued inequalities that permeate modern British society. The rest of this article therefore will look at these demands in an attempt to evaluate the degree to which we have fulfilled the demands of the GLF manifesto.

“Before we can create the new society of the future, we have to defend our interests as gay people here and now against all forms of oppression and victimisation. We have therefore drawn up the following list of immediate demands.”

- “that all discrimination against gay people, male and female, by the law, by employers, and by society at large, should end” – In December of 2020, Ken Maginnis of the House of Lords was given an eighteen-month ban from the house for proven homophobic bullying and use of derogatory language, but will be allowed to return. It therefore seems that the culture of the workplace, even that which is ostensibly the most powerful and civilised, is still saturated with homophobia, and the system functions to protect perpetrators rather than victims of sexual discrimination. (see https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-55171974)

- “that all people who feel attracted to a member of their own sex be taught that such feeling are perfectly valid.” – one can only presume that coming out as LGBTQ+ today is less dangerous than in 1971, however, the subjectivity of social, economic, political, and cultural circumstances among others mean that it is not a safe and caring process for all.

- “that sex education in schools stop being exclusively heterosexual.” – Indeed the compulsory relationships education, relationships and sex education and health education introduced in 2020 does address LGBT experiences and relationships, however, parents remain entitled to withdraw their children from this vital education, thus enforcing barriers to learning that can be harmful for themselves and others.

- “that psychiatrists stop treating homosexuality as though it were a sickness, thereby giving gay people senseless guilt complexes.” -homosexuality itself in the UK is no longer an illness under the domains of mental disorder. However, studies have shown that the guilt complex has not been eradicated, and that gay people disproportionately suffer from mental health issues, with lesbians the most likely group to commit suicide.

- “that gay people be as legally free to contact other gay people, though newspaper ads, on the streets and by any other means they may want as are heterosexuals, and that police harassment should cease right now.” – this is one area through which we might access a glimpse of progress: such contact is indeed free and legal, but that does not safeguard queer people from attracting abuse and negative attention whilst exercising this right in public.

- “that employers should no longer be allowed to discriminate against anyone on account of their sexual preferences.” – any form of discrimination in the workplace is, in theory, illegal. However there is no comprehensive way to enforce this law upon every employer.

- “that the age of consent for gay males be reduced to the same as for straight.” – thirty years after the foundation of the GLF, the sexual offences amendment act did reduce the age of consent for gay sex to 16. But the prejudice remains that many gay and trans youths are considered ‘too young’ to know of their sexuality or identity for certain, and the idea that they will ‘grow out of it’ persists.

- “that gay people be free to hold hands and kiss in public, as are heterosexuals.” – once again, there is a gulf between theory and practise. According to Stonewall’s 2017 report ‘LGBT in Britain – Hate Crime’, 21% of LGBT people have experienced a hate crime due to sexual orientation and/or gender identity in the last 12 months, increasing to 41% of trans people. However, 81% of LGBT people who experienced a hate crime did not report it to police. This indicates that there is still an inherent inequality in police response and attitudes to discrimination for LGBTQ+ individuals, in comparison to cisgender heterosexual people.

The GLF had disbanded by the end of 1973, but they laid a precedent for the demands, organisation and discussions of later LGBTQIA+ movements, indeed much of the discourse of gay liberation in the 80s and 90s was founded on the core principals outlined in this manifesto. Commemorating its half centenary therefore not only calls for celebration, but for the continuation of the plight to end systemic oppression and the marginalisation of queer folk.

For related support and resources, see https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/welcome/2020/wellbeing/connect/lgbtq.aspx

Sources:

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/oct/12/gay-liberation-front-social-revolution

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/gay-liberation-front-manifesto#

Relationships and sex education (RSE) and health education – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)