Valentines day. We have all come to love or loathe the mass capitalist phenomenon that has appropriated the hagiographical tale of a third century Catholic martyr, and forced the lucky ones among us to fork out for a nice dinner and a bunch of flowers. But one tradition of valentines which I am desperate to make a comeback is that of the vinegar valentine, essentially a type of hate mail loved by the Victorians.

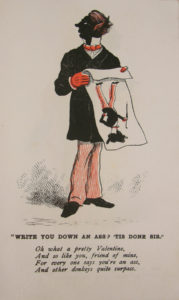

The eighteenth century saw the emerging trend of simple cut and folded paper valentines tokens, whilst in nineteenth century Britain, the exchange of valentines cards saw unprecedented levels of success; 200,000 Valentines cards were sent in the 1820s, increasing to 1.5 million fifty years later, the market exploding as a result of mass production. The 1840s-80s in particular saw the popularisation of the single sheet vinegar valentine, considerably cheaper to print, buy and send. These rude, mocking valentines were exchanged anonymously within a much wider network than the love token, given to colleagues, neighbours, members of the community and unwanted partners, ridiculing the intended viewer for a variety of social ills, from poor hygiene to pretentiousness, anti-social behaviour to alcoholism, complete with crude caricature images representing the recipient. Such cards survive in much smaller numbers than love tokens, as their scathing comments would illicit shame and anger, subsequently being destroyed by the humiliated addressee. They are also largely ephemeral on account of their popularity with the lower classes, less constrained by the paradigms of respectability, as well as being so very cheap.

That being said, there is a sizeable album of these vinegar valentines dated to around 1870 held in the Royal Pavilion art Galleries and Museum, Brighton and Hove, which illuminates this fascinating tradition of personal ridicule. Annabella Pollen is an expert on this collection, and has described the practise as “part of a much longer tradition of social and moral policing of behaviour within one’s close community.” But who and what exactly were they targeting?

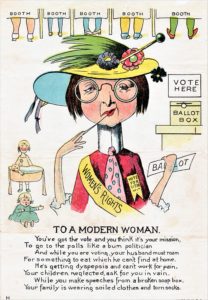

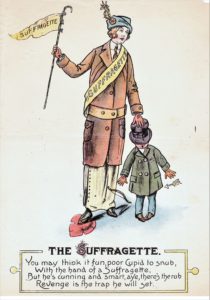

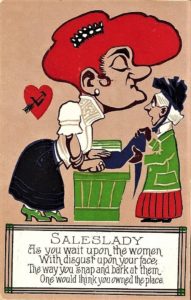

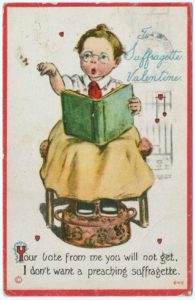

A frequent target for ridicule was someone who overdressed, implying a social rank of which they were not a part. Massively oversized bustles and headdresses, the symbol of the proud peacock, and lowly men depicted donning gentlemanly apparel are frequently mocked. Another topic was gender role transgression: women as unkept, or as scolds and nags, and weak men shown taking care of children. Some simply seem to be insinuating the end to an unwanted attachment, or are pretty much insulting for no apparent reason. It appears some were gentle and playful in tone, while others were downright cruel, and would likely have caused considerable upset to the recipient, which was likely the intention especially in the mocking of antisocial, unorthodox behaviours. For example, the practise took on greater significance in light of the suffragist movement, propagating the popular trope of suffragists as unattractive and unwomanly.

There are countless ways that vinegar valentines can help inform historical research, from societal roles, networks of personal relationships, political propaganda and so on, but I also think they’re a good old piece of fun. Here are some of the most entertaining ones I’ve found from Britain and also the other side of the pond – feel free to send them to your friends!

For more, see Annabella Pollen, ‘”The Valentine has fallen upon evil days”: Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque’, Early Popular Visual Culture, special issue: Social Control and Early Visual Culture, Vol 12, Iss, 2, 2014, pp. 127-173

Sources:

Pollen’s above article

Love letters and hate mail: Victorian vinegar valentines – Discover (brightonmuseums.org.uk)

Insult & Vinegar: valentines cards for the one you loathe – Discover (brightonmuseums.org.uk)

The Rude, Cruel, and Insulting ‘Vinegar Valentines’ of the Victorian Era – Atlas Obscura