The Guardian’s recent investigation into misinformation in 100 trending videos with #MentalHealthTips makes some important points.

They found that 52% of the videos included advice that contained misinformation, with other content that was ‘vague or unhelpful’.

False information about mental health has serious consequences, such as leading people to take ineffective treatments or ignore medical advice, which may escalate when posts are shared by influencers and ‘go viral’ (see Mulcahy et al., 2024)

But is this the whole story?

Our research examined the advice from 90 influencers who talk about mental health in their TikTok videos. We looked at the comments from a set of 600 videos to identify which videos might be likely to provide help or provoke harm. We asked a panel of seven mental health professionals and a panel of seven experts by lived experience to evaluate the videos which had comments suggesting they were the most helpful and most harmful from three types of influencers: Health Professionals, Wellness Figures and Lived Experience Experts.

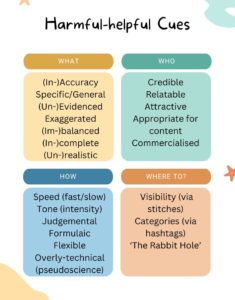

Our panels identified many of the same problems discussed in the Guardian report. But they also found a wider range of ‘cues’ that could lead to helpful and harmful outcomes in terms of mental health literacy.

It’s not just that the videos may contain content that is inaccurate, over-generalised, imbalanced, partial or unrealistic.

If the content is delivered too fast, with a judgemental tone or in a formulaic manner, even good content might be ignored.

The credentials and appearance of the content creator also matter. Whether the credentials of the content creator are genuine, and what those qualifications may permit the creator to give advice about need careful consideration. The details are often buried in sites linked from landing pages rather than obvious from the video itself.

The networked content in TikTok also means that using formats like a Stitch might give viewers access to unhelpful content, even if the influencer is adding a video to provide correct information afterwards.

Lastly, not all the mental health content from influencers on TikTok is unhelpful. We’ve also been studying what young people find helpful and what we can do to further support that.

There are great initiatives to promote reliable health content, like TikTok’s Clinician Creator Network.

While we need to be aware of misinformation, we also need to put this in a bigger picture, alongside content which is useful and developing regulation and strategies that maximises the good, while mitigating risks of harm.