Under the pressures of the Great Depression, the predominantly agricultural states of interwar East Central Europe resorted to economic policies that were particularly protectionist in character. In an era when international relations were increasingly characterised by hostility and territorial revisionism, many feared that economic weakness could easily lead to a loss of sovereignty, if exploited by increasingly aggressive neighbours, such as Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union.

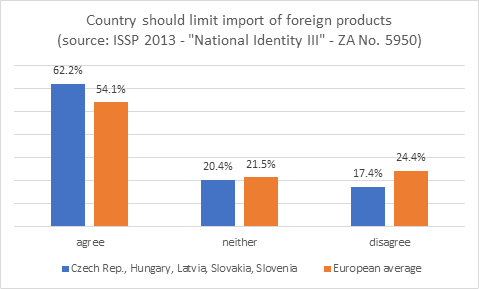

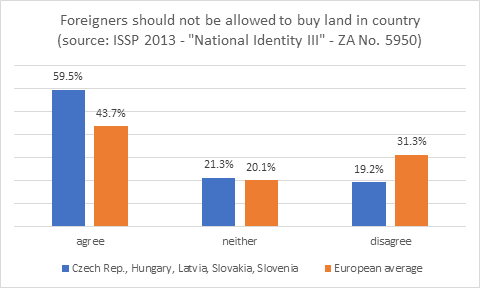

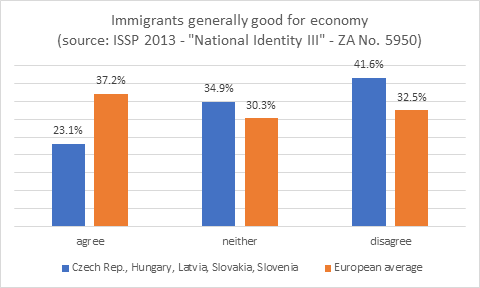

It is striking that 90 years later, support for protectionism remains invariably high across the region. The International Social Survey Programme: National Identity, which was carried out three times from 1995 to 2013, shows that expectations towards economic policies guided by nationalist principles is significantly higher in the post-communist states of East Central Europe that participated in the survey (Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Slovakia and Slovenia) than across Europe on average.

In 2013, 62 per cent of interviewees claimed states should limit the import of foreign products (54 per cent European average). 60 per cent believed foreigners should not be allowed to buy land in their countries (44 per cent average). Strikingly, only 23 per cent believe that immigrants are generally good for the economy (37 per cent average), although this has increased from only 14 per cent in 1995.

This support for protectionism is linked to a broad pessimism towards the economic capabilities of these states. Consistently, East Central Europeans showed less pride in the economic achievements of their home countries than citizens elsewhere in Europe: In 2013, 71 per cent in these five countries stated they were not proud, as opposed to 50 per cent across Europe.

Yet while these positive views on economic nationalism have been relatively stable across the two past decades, support for nationalist foreign policies have worryingly increased: Today the proportion of East Central Europeans who believe that their countries should follow their own interests even if these clashed with those of their allies is slightly higher (by 1.7 per cent) than the European average, although it had been significantly lower in the past (9 per cent lower in 1995 and 11 per cent lower in 2003).

Klaus Richter (Reader in Eastern European History)