Global economic crises like the Great Depression hit countries at different times, with various intensities, and great local and regional disparities. Some social categories are more affected than others, and the impact of crisis in one sector of the economy may have unexpected effects elsewhere. As part of my preliminary research for the project The Liminality of Failing Democracy: East Central Europe and the Interwar Slump, I explored this premise by looking at urban workers in Romania, a still overwhelmingly agricultural country, in the period between 1928 and 1932.

During this time the official statistical yearbooks recorded the “cost of living index” for fifty towns in Romania. The cost of living was calculated using the “average prices” from each town for the “strictly necessary expenses of a (middle-class) family composed of five members.” While the selection of towns varies, I identified many that are present both in the “cost of living index” and the separate “wage index” statistics for the entire period. The latter specifically refers to “working-class wages,” which presumably include workers in industry and manufacture but not domestic servants, commercial workers, and others. It also excludes the unemployed, probably more numerous than officially recorded from 1928 onwards. Both primary and secondary sources refer to “shadow unemployment,” although its extent remains unknown. For these many reasons, the statistics only provide a partial image of life in Romania’s urban centres. Still, the existing data indicates that in many towns the “cost of living” index declined faster than the wage index, most likely because of sliding food prices. Thus, for those still employed, life temporarily became cheaper.

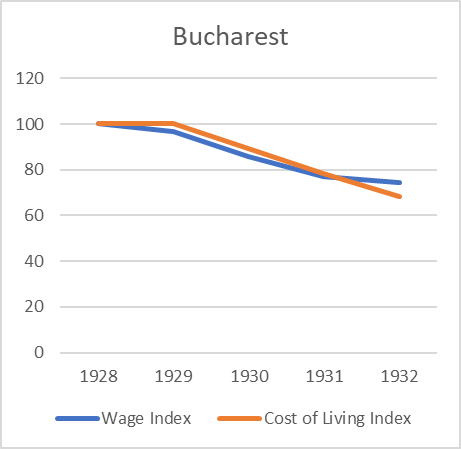

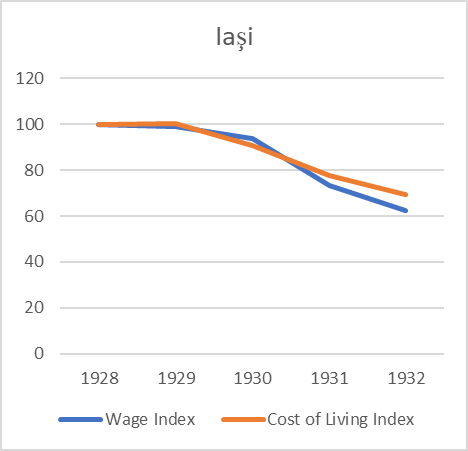

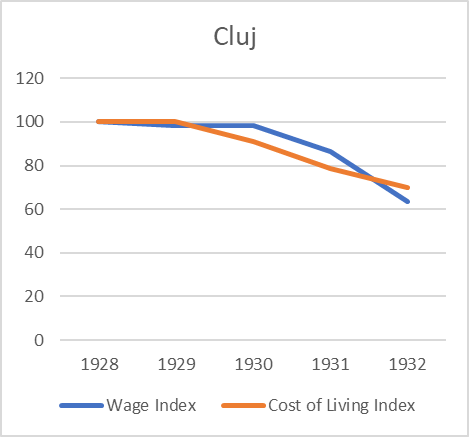

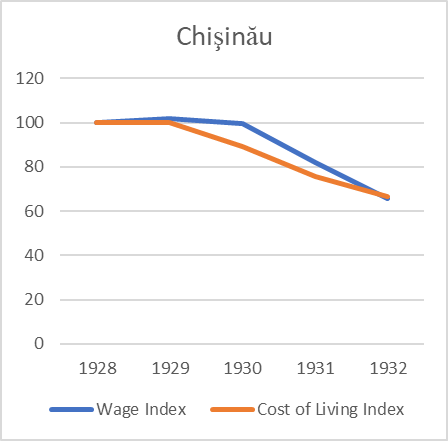

I compiled data for Bucharest (Fig.1), the regional capitals of Iaşi (Fig.2), Cluj (Fig.3), Chişinău/Khishinev (Fig.4), and other towns from each region. The outlier is Iaşi, the provincial capital of Moldova where, for reasons I have yet to determine, wages declined faster than living costs. Bucharest also stands out, probably given the density and diversity of its industries. Here the wages and the “cost of living” declined at very close rates from 1928 until 1931, when the cost of living started to drop faster.

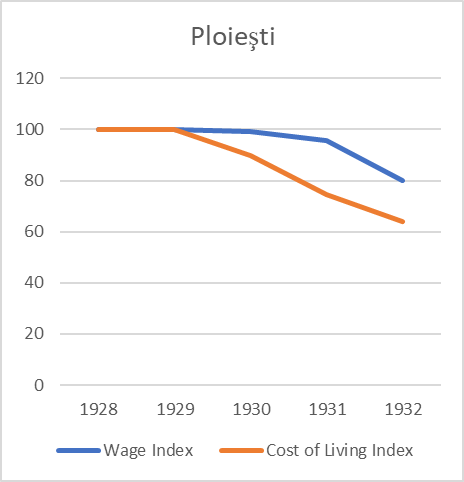

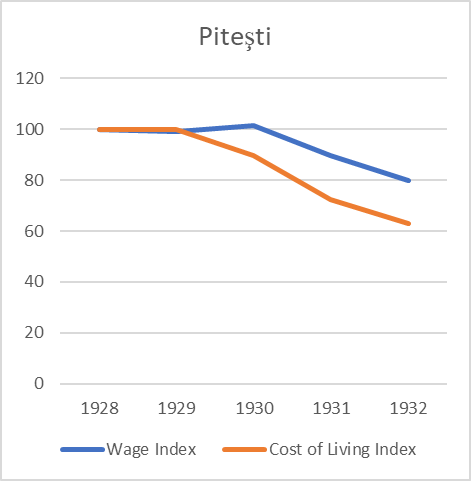

Conversely, the data for all other towns suggests that living costs fell faster than wages. I have deliberately included Ploieşti (Fig.5), the centre of Romania’s lucrative oil industry, which shows a wider gap between decreasing costs and wages. Although Ploieşti could have been an exception, Piteşti (Fig.6) and Craiova (not shown here), also in Wallachia, display similar patterns, suggesting a broader trend.

The data gathered here is incomplete and problematic. However, it raises important and intriguing questions. It confirms the necessity of a detailed chronology of the Great Depression, according to country, region, and social category. It also asks whether developments in some areas of the economy could have inversely affected others. Economic crises are complex phenomena that can also create opportunities. Statistics like these remind us not to dismiss this possibility.

Source: Anuarul Statistic al României (Romania’s Statistical Yearbook) for 1929, 1930, 1931-1932 and 1933.

Anca Mandru (Gerda Henkel Research Fellow)