In our first post of 2024, Catherine Clarke, PhD candidate at Keele University reveals the findings of a research visit to the British Library, made possible through a Midland History bursary.

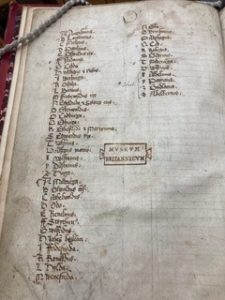

In 2023 I was able to visit the British Library to carry out research for my thesis on the monastic houses of Shropshire. One of the manuscripts I studied was Lansdowne MS 436, which once belonged to the Benedictine nunnery of St. Mary and St. Æthelflæda at Romsey. The manuscript was written some time in the first half of the 14th century and is a collection of British saints’ lives. The manuscript is comprised of 132 folios with large puzzle initials in blue, red, and purple, often with blue foliate decoration. There are pen flourishes forming borders with large initials in red with purple penwork decoration. The table of contents (see Figure 1) indicates there were originally four more lives than the extant 43. The lives relevant to my project are those of Saint Milburga of Wenlock, who I will focus on here, and Saint Winifred who is associated with Shrewsbury Abbey.

The life of St. Milburga can be found in a number of other texts, such as the 13th century MS 149 held by Lincoln Cathedral Archives, but until the publication of the Catalogue of the Manuscripts of Lincoln Cathedral Chapter Library in 1927, the life of St. Milburga was known only through Lansdown MS 436 and William of Malmsbury. The author of Lansdowne makes it clear that their life of Milburga was copied from an earlier text and although the MS belongs in the Lincoln group of lives, it has certain marked differences. This MS begins with a much longer genealogical introduction and does not include a Testament or any of the homiletics found elsewhere. The miracles and an account of the discovery of her bones are included but they are abridged and none of the Welsh miracles are included.

There are no clues in the text as to where it was produced, or the identity or gender of its author. However, it has been suggested that its ownership by Romsey, taken together with its inclusion of the lives of several female saints, could mean that it was intended for a female audience. It has been argued that the author reworked the source material to suit the spiritual and educational the needs of female religious, and that it may have even formed part of a program to remediate Latin literacy in nunneries. The author took the same approach in the production of the Life of St. Winifred, carefully selecting and integrating material from different versions of her life.

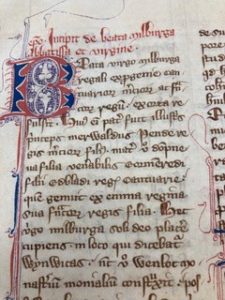

The first lines of the Life of Milburga read:

Incipit de beata Milburga abatissa et virgine. Beata virgo Milburga regali ex progenio canturiorum merciorum ac Francorum regum exorta refultsit. [It begins with the blessed Milburga abbess and virgin. The blessed virgin Milburga rose from the royal lineage of the Mercian cantors and kings of the Franks.] (Figure 2)

The author continues; her father was the illustrious prince Merewald, son of the King of Mercia and her mother was Dompneva, the daughter of the venerable Eormenred, son of King Edbald and Queen Emma, the daughter of the king of Franks. The virgin Milburga, desiring to please God alone, in a place that was called WynWicas. Now called Wenlock, there was built a monastery for nuns and it became rich in possessions. There, gathered together with a multitude of virgins and devout widows, she assumed the habit of the holy religion with a veil.

The rest of the life continues as one would expect until the account of the Invention of her bones, following the re-founding of the house by Roger, earl of Shrewsbury in 1072.

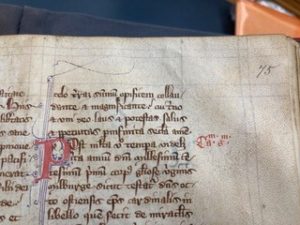

Post multa vero tempora videlicet circa annum domini millesimum centesimum primum corpus gloriose virginis Milburge. [After a very long time, namely about the year 1100, the first body of the glorious virgin Milburgha [was found]]. (Figure 3)

The house had been populated with monks from the Cluniac priory of La Charité-sur-Loire, who soon after their arrival, discovered the bones of St. Milburga whilst repairing the nearby ruined church of Holy Trinity. Lansdowne ascribes this church to the nunnery but does not include the popular account of St. Milburga’s remains being discovered when two children fell into her grave, but instead claims that the monks were encouraged to dig in the appropriate place by Anslem, Archbishop of Canterbury. That St. Milburga allowed herself to be discovered by the newly arrived Cluniac monks, and then began to perform miracles, showing local people that their saint was happy with the new community, allowing Roger’s foundation to flourish.

Whilst parts of this manuscript have been transcribed, thus far I found no full transcription of the life of Milburga it contains, and so hope to continue working with this MS in the future. I am thankful for the bursary from Midland History that allowed me spend time at the British Library exploring this beautiful manuscript.

Bibliography

Baring-Gould, Rev. S. The Lives of the Saints. Vol. 2. 16 vols. Edinburgh: John Grant, 1914.

Baugh, G.C. The Victoria History of the County of Shropshire, Vol.10. Wenlock, Upper Corvedale, and the Stretton Hills. Victoria History of the Counties of England. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Edwards, A.J.M. ‘Odo of Ostia’s History of the Translation of St. Milburga and It’s Connection with the Early History of Wenlock Abbey’. PhD Diss, University of London, Royal Holloway College, 1960.

Edwards, A.J.M. ‘An Early Twelfth Century Account of the Translation of St. Milburga of Much Wenlock’. Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological Society 57 Part II (1962), p. 134.

1 thought on “Lansdowne MS 436 – The Romsey Legendary”