A guest blog piece from Gin Warren, Doctoral Researcher at the University of Cambridge. Gin attended the Centre for Midlands History and Cultures conference, ‘Landscape and Green Spaces in the Midlands: New Directions in Garden History’ held at Winterbourne House and Gardens in July 2024.

‘Keep off the grass’: subtle ways to exclude poor people from ‘public’ green spaces

What was Henry Jenks, the mayor of Shrewsbury, thinking when he had avenues planted on Quarry Common around 1720? He probably saw his gesture as a generous one which would improve the aesthetic and amenity value of the grassy expanse. There would be shade on sunny days, and his gift would offer a new place for the town’s riders and walkers to see and be seen as they promenaded – Shrewsbury’s answer to London’s Hyde Park or The Meadows in Edinburgh.

John Bowen captured the ‘before’ scene in his ‘Prospect of Shrewsbury from Kingsland’ painted just before the four hundred lime trees went in to define the first of the ‘Polite Walks’ (Figure 1). You can see the washing spread out to dry on the bushes, but Bowen doesn’t seem to have recorded evidence of the skinny dipping, that Jude Piesse tells us, was one of the many uses of the common and river. She reflects on this gentrification, gradually denying Shrewsbury’s poor opportunities for their many traditional uses of the Quarry Common.

Jenks’ gesture may still have peeved some over a century later. Shrewsbury’s MP, Robert Slaney, was a driving force through the 1830s and 1840s in a chivvying Parliament about the wellbeing of the urban poor, including their access to green spaces. Political historians of nineteenth century social reform tend to skip over this issue. But Christopher Hamlin, who describes Slaney as ‘an old fashioned philanthropist…a Whig squire…trained as a lawyer’ writes that ‘throughout the early 1840s Slaney repeatedly urged the Government to … build parks, even swimming facilities’.

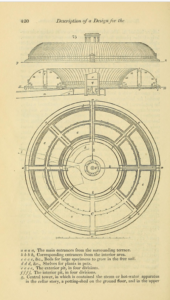

The shareholder-members of the Botanical and Horticultural Society of Birmingham seem to have been unconcerned for others’ welfare. John Loudon only claimed expenses for designing their new Botanic Garden in 1831. They bitterly disappointed him by rejecting this state-of-the-art hothouse (Figure 2).

Description of a design for the Birmingham Botanical Horticultural Garden (hothouse)

Operationally, they opted for restrictive rules, unwelcoming opening hours and patrolling policemen. Phillada Ballard’s 1983 history of the garden commends them for opening to the public on Mondays and Tuesdays for 1d a person from October 1844. Whereas Louise Wickham takes a revisionist view that this was a public relations exercise as it must have been obvious to everyone that working people could not benefit from this ‘kindness’ when at work on those days!

Sources:

Ballard, P., An Oasis of Delight (London: Gerald Duckworth 1983), p. 35.

Conductor (John Loudon) Description of a Design made for the Birmingham Horticultural Society, for the laying out of a Botanical Horticultural Garden, adapted to a particular situation. The Gardener’s Magazine, 8 (1832), pp. 407-28.

Hamlin, C., Public Health and Social Justice in the Age of Chadwick. Britain, 1800-1854 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 147-8, 246-8.

Piesse, J., The Ghost in the Garden (London: Scribe Publications, 2021), pp. 126-9.

Wickham, L., Gardens in History: A Political Perspective (Oxford: Windgather Press, 2012), p.167.