Over the summer two University of Birmingham Students undertook a College-funded Collaborative Research Internship with current MBS Director Dr Sarah Kenny. They explored the archives of the YMCA which are housed at the Cadbury Research Library. Here BA History student Carina Walker shares her reflections on what these archives offer historians.

“They’ve Got a New Kind of God”: Celebrities, Pop Music and the YMCA in the Sixties

“Are teenagers only concerned with the current trends, pop, beat, fashion and speed or is this picture unfair?” asks a 1966 article in YMCA World, recently retitled from The YMCA Review, making the Association’s underlying concerns explicit. In 1960 the Albemarle Report called for reform across financial, structural and personal areas of youth work, whilst the Association reckoned with the declining relevance of evangelism and increasing moral anxiety about youth culture throughout the decade. Increasingly, the Association aimed to appeal to young people on their own terms and simultaneously emphasise the fulfilling nature of Christianity. While emphasising the public perception of ‘pop’ and ‘beat’, the rhythm and blues influenced genre that The Beatles were a part of, as trivial, commercial distractions from more valuable activities, the new approach is clear in the long-running national publication’s use of popular musicians to engage its readers. Interviews with The Beatles and Cliff Richard demonstrate how the Association examined and responded to the world of pop music.

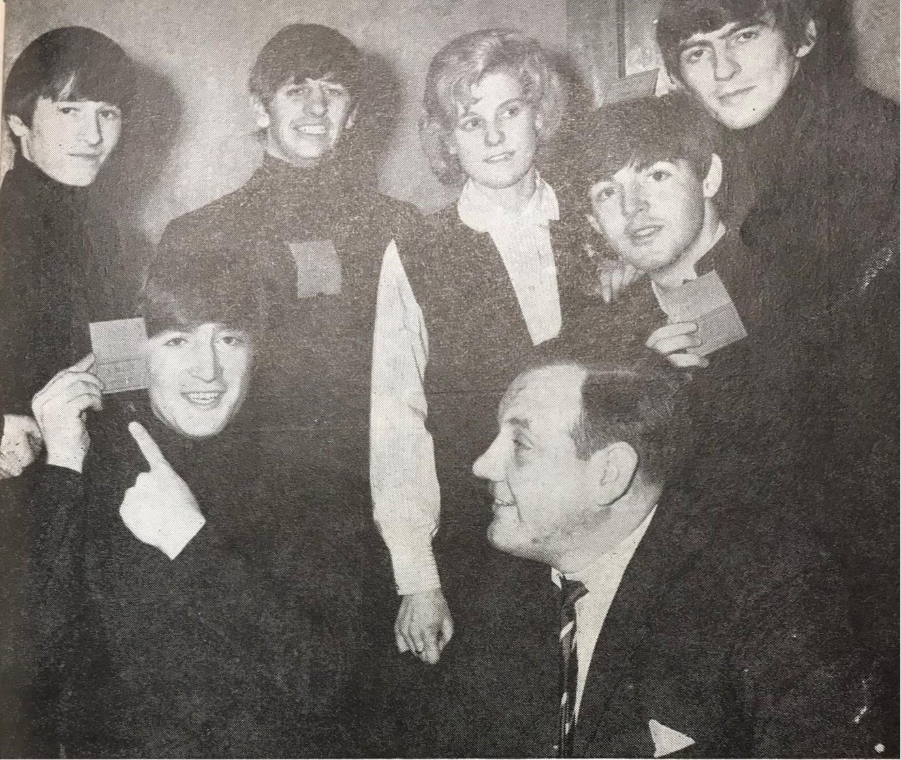

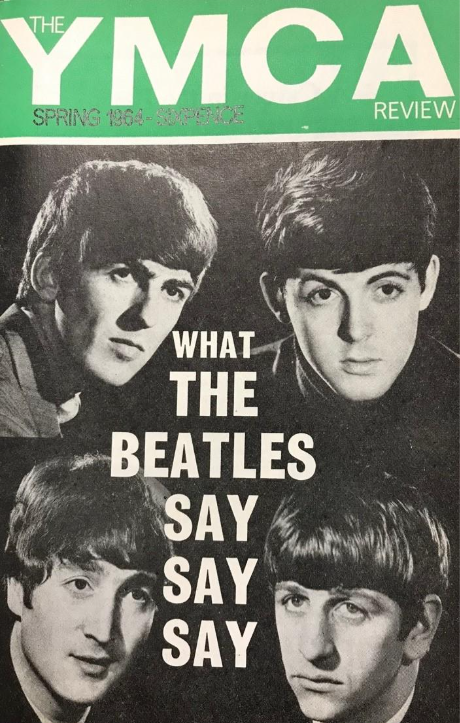

Although Elizabeth II was featured on the Spring 1961 cover, The Beatles were the first celebrities to appear on the cover of The YMCA Review. By 1964 the covers had a magazine-like format with a colourful masthead and bold main cover line, updating its more traditional news coverage to be more eye-catching for its young members. It is evident the Association understood the massive influence The Beatles had on popular attitudes, as they were given membership cards and symbolically ‘recruited’ into Woking YMCA, appealing to the multitude of fans wanting to emulate them. The interview itself is especially focused on exploring how the band’s personalities and charisma connect so strongly with teenagers. They are described with awe-struck reverence, for example, Paul is labelled ‘the supreme diplomat’ of the group, with their roles integral to their success. Nonetheless, they relate easily to the young people around them. In particular, Paul deems a YM member with a Beatles haircut “one of us” and the article’s title ‘The Beatles Answer Back’ shows how synonymous they are with youthful misbehaviour.

However, any more specific insights into youth culture that the Association might hope to gain from The Beatles are kept illusive. When asked whether their success is due to their style, sound or other reasons, the group replies ‘it’s just lucky that so many share our taste that’s all’, emphasising their ineffable charm. Although there is no mention of Christianity, the Association’s other principles are still present. The questions which focus on the band’s life and career ‘satisfaction, besides the financial’ show its aim to help young people moving into adulthood and thinking about their purpose and place in the world.

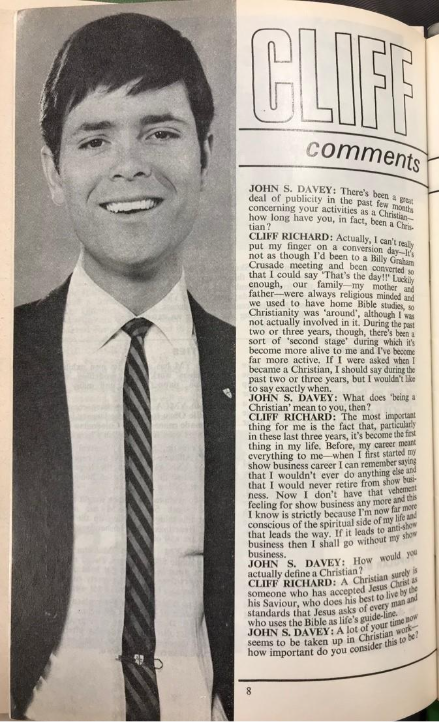

While Cliff Richard is also a cover image, he appears in a very different context than The Beatles who were at the height of their fame. No longer just a musician by 1967, Richard was an active evangelist, sharing the moral concerns of the YMCA. More than double the length of The Beatles interview, the interview goes into depth about how Richard’s Christianity entwines with his celebrity. When presented with a similar question about career success and satisfaction, Richard presents Christianity as an antidote to showbusiness hedonism and a way to ‘get answers to [the] problems’ of adult life. Anxieties about directionless, materialistic teenagers are clearly illustrated when Richard states that young people spending too much money on pop music ‘is a danger really to themselves because they’ve got a new kind of god’, comparing intense fandom and consumerism to idolatry.

Nevertheless, the interview explores the balance that needs to be struck to appeal to young people. Echoing other YMCA World articles, Richard acknowledges that direct, Church-bound preaching is no longer effective as non-Christians are ‘liable to be ‘put off’’. While the Richard’s celebrity, like The Beatles’, is presented as useful for drawing attention, it is not meant to overshadow the Association’s work. Richard is keen to stress that missionary work must not change too much to accommodate pop music trends or else ‘the point is lost’. Although the interview’s theology is so broad almost to the point of being bland, it still reveals the current attitudes towards young people. Richard’s assertion that ‘they have to stick to these rules […] as they come from the Bible in the first place’ shows anxiety about the cultural relevance of the Bible and the desire to provide structure for rebellious teenagers.

Overall, these interviews show that while the YMCA’s publication featured celebrities to its advantage to entice readers, it was still ambivalent about the impact of fame and pop music on youth culture. Consumerism and hedonism are evidently clear concerns that Association aims to solve with its evangelism.

Carina Walker (BA History, final year)

You can find out more about the YMCA collections here.