A few months on from the inception of (In)security, our collaboration with Digbeth’s Eastside Projects gallery, we spoke to a few of the participating artists, asking a few questions in order to better understand both their projects and their own perception of urban insecurity. Below are the artists’ insights, including a couple of early images from one of the projects!

Q: What interested you in the (In)security project and why did you want to get involved?

Chloe Sami: I was interested in the idea of safety and the theme of perspective and narrative when looking at the (in) security project. I thought about how I might be perceived, as a Asian woman of colour, in different settings. How safe I would feel, in certain settings, and how safe, or unsafe, my presence may make others feel. Every individual person’s view of their own personal safety will be very different.

Faisal Hussain: My practice began engaging with some of the subjects covered in the ‘(In)Security’ commission some years ago and therefore it felt a natural progression to apply! I attended the project’s presentation and discussion, and subsequently liaised with several academics including Dr Katharina Karcher and also meeting Gavin Wade and Ruth Claxton from Eastside Projects. The Q&A initiated my questions surrounding the security measures in place in other public spaces where attacks have taken place against minority communities, such as places of worship, work and recreation. ‘How can people feel more secure and what else impacts on the feeling of insecurity in different public spaces, including high streets, city centre, shops, places of worship etc.?’ During the presentation and discussion of the ‘securitizing’ public space, I posed the question around deciding what requires protection and who and by whom? Through the discussion I was reminded of ‘Project Champion’ in Birmingham (2010/11) and other instances of how spaces are ‘protected’ by the state and what and who seems to be the priority, what are the blurred lines between protection and privacy.

Alejandro Acín: I really liked the challenge of responding creatively to such a complex theme. For those of us that don’t work regularly on issues around terrrorism or counterrorism, most of the interactions that we have are through the news outlets or government press conferences after particular events happened. Therefore, I thought this would be a very good opportunity to understand the complexity of this topic by doing a historical research that contextualises the present situation as well as to identify the “silencies” in the production of academic knowledge about the topic. Working alongside academic experts on the field has been a very valuable and rich experience so far.

Q: What impact do you think academic research might have on your artwork, and in turn how do you think your artwork might be able to influence academic research on urban safety and insecurity?

Chloe Sami: As I am looking mostly at narrative research, I’ve been interested in how the role of questioning, interviews and questionnaires can influence the information I receive from the women I speak to. This will directly influence the words, stories, and therefore mood and emotion, I embody for my performance piece. I hope my piece will encourage academic researchers to look further into the realms of safety from a BAME and female lens. I feel that much of what we consider to be a normative perspective, including safety, is actually a white male viewpoint and opinion. These viewpoints are what put safety legislations and actions in place. I would like to see a broader and more diverse range of opinions researched and catered for.

Faisal Hussain: I hope to understand academic analysis and data into how spaces and people in those spaces are evaluated differently under government legislation. I would also like the insight into how spaces are analyzed and estimated for ‘threat’ from a corporate and business perspective. Working with all the academics on the project has been invaluable and has given me some insight and inspiration to explore these issues. In turn, I think that my work could provide some insight and perspective as an artist. Engaging and navigating these spaces, as a person of colour, I hope my points of reference will be of use. With the current legislation, which has often been accused of being misused, I hope that my critique and the work I produce will provide an example of artistic response to the data made available and shared between academic colleagues.

Alejandro Acín: The research process has been very interesting so far and it opened various lines of creative inquiry for me. It also helped me through the data collection process that will back up some of the arguments I am responding to. Although meaning-making from experience through the arts ‘works’ for me, it might not for everyone, in much the same way that using numbers and statistical analysis might limit this capability. This is why I think academic research and artistic practices must establish dialogues that produce multifaceted knowledge. I guess academic research encourages the demand for clarity, form and method, so creative processes can and should lead to unexpected results in one’s own research. During the last years of my creative practice I have been interested in exploring ideas around “archival silence”, the existing gaps in an official system of knowledge whether visual, oral or written. One of the leading references that I have found while researching for this commission is in relation to the silences in academic and literary production about state terrorism, its definition and its ommision while discussing contemporary cases. These silences or “ghosts”, like Richard Jacks (2008) denominates in his article The ghosts of state terror: knowledge, politics and terrorism studies, have two orders of criticism: “the first-order is the absence of state terrorism is criticised for its illogical actor-based definition of terrorism, its politically biased research focus, and its failure to acknowledge the empirical evidence of the extent and nature of state terrorism. A second-order critique entails reflecting on the broader political and ethical consequences of the representations enabled by the discourse.” A very good introduction to State Terrorism has been Steve Hewitt’s chapter on Faces of state terrorism (2012) where he says that the “best starting point is precisely an understanding of the “hegemon’s” objections: the US (and the UK with them; but not Germany or France, for instance) do not want a precise definition, as they prefer to retain their “right” to call “terrorists” those they perceive as enemies, and clear of that taint those they consider friends or allies. This made me think further about the consumption of “terrorism”, its visual representations and the sophisticated production engine mainly dominated by the official discourses that inform some of the current counter-terrorist strategies. For this commission I am using the case study of the “War on Terror” led by the US, the United Kingdom and Spain on Iraq and Afghanistan after the 9/11 event which Habbermans describes as “the first historical world event in the strictest sense”.

Q: Can you briefly describe your work on this project so far?

Chloe Sami: I have interviewed women of Birmingham to find out what their thoughts on personal safety and security are. Their personal narratives, thoughts and stories are very important to me, and I hope to be able to use them anonymously in an Operatic piece. I am using the opera aria ‘Shall we Never See The End of This?’ from Menotti’s opera The Consul, as a frame in which to weave the women’s narratives on. I am unsure whether this piece will be live or digital yet, so there are still many creative avenues to go down!

Faisal Hussain: So far the 3 proposals I have put forward have begun to converge. The initial ideas have been shared but I am very keen for the critical eyes and thoughts of the team to make the work the best it can be. The work at the moment is a combination of different research elements that include; the barriers used in public spaces, information and data alluding to different state security initiatives and how race and identity are a factor in the criminalising of individuals and groups in those spaces. Part of my arts practice already includes the use of different retail signage and street furniture as a key element. The context of how these will be shown is still in discussion but I am hopeful that a physical form will be produced ideally in a public space with some representation of the work in a gallery space.

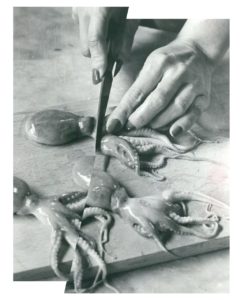

Alejandro Acín: Taking Wittgenstein’s argument that language mirrored

reality, mirrored the world, the main raw material for this commission has been the language used in the legal definitions and media representation of terrorism after the 9/11 and the counter-terrorist strategies that follow. The final outcomes will result from my interaction with this language in two different ways: creating visual constellations (subjective) and transforming them into dual objects (objective). Inspired by Aby Warburg’s Atlas and Jacob Burckhardt’s identification of a subjective presence in the study of the past, I am creating a visual constellation (a group of images sourced from historical archives, media outlets, civilian footage, the internet…) organised under specific conceptual categories (Terror, fear, security…) even if these are sometimes aleatory (based on formal relationships). I am interested in the meaning that comes from chaos. One of the first documents I found during this process is HMS Terror’s logbook, a battleship converted into a discovery vessel that got lost in 1894 while trying to do the Arctic passage. The HMS Terror wreck was discovered in 2006 including all 129 explorers that were lost when the vessel became encased in ice – with some resorting to cannibalism. I am using the story of this vessel as a metaphor what Burckhard states in the introduction of Civilisation, where he acknowledged the influence of the historian’s subjectivity in the interpretation of cultural and artistic sources: “In the wide ocean upon which we venture, the possible ways and directions are many; and the same studies which have served for this work might easily, in other hands, not only receive a wholly different treatment and application, but lead also to essentially different conclusions.” (Burckhardt, 1878: 4) Transatlantic fictions to visualise “the resurrection of fears and anxieties that were dormant but not dead” after the 9/11 event (Araújo, 2015). In order to counter my interpretation of State Terrorism and its historical context, I am also juxtaposing this with an exploration of a present reality such as lone ‘wolf’ attackers using knives. In order to do so I am transforming stacks of printed British Terrorist legislation into knives using laser cutting techniques (using knife sillouthes from real attacks) while acknowledging the double edged sword” language used when defining these attacks as terrorists. Knife crimes have become a very important security concern in the UK in recent years but “what knives are considered terrorist objects?”