This post was contributed by Naomi Pullen, at the University of Warwick. It is part of our Magical Source series, in which historians from Birmingham and Warwick discuss the sources that reshaped their thinking on a topic. The first entry, by Karen Harvey, was about Mary Toft’s Confessions. The second, by Charles Walton, was about Paine’s Letter to Danton. The third, by Ben Jackson, was about Lord Grantham’s Coach.

Naomi Pullen on the Quakers’ John Locke Letter

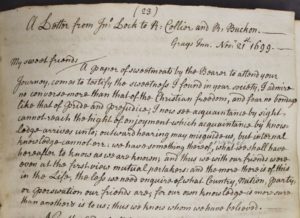

My magical source is a letter sent from John Locke to a Quaker preacher called Rebecca Collier, in which he outlines some of his thoughts and views on female preaching after he had heard her and her companion, Rachel Brecken, preach at a Quaker meeting in London. There was a short marginal note to say that Locke had altered his views on female preaching on the basis of this encounter with Collier and that he had subsequently revised his Notes and Queries on this subject. There was also a rather baffling story that King William III had been in attendance at the same meeting, dressed incognito.

I discovered the source during my PhD research at Friends House Library in London when I was looking at the experiences of non-preaching Quaker women. The whole document struck me as quite interesting, partly because of the status of the people involved in the letter, and partly because of what Locke seemed to be suggesting in support of women’s preaching.

After a conversation with my supervisors, who thought this could be quite a significant find, I looked at the complete collection of Locke’s edited correspondence by E. S. De Beer and found a mention of the letter, though it had been dismissed as a fake. De Beer concluded it was spurious for three reasons. Firstly, because of the inconsistent dating of the letter, which he had identified as 21 November 1696 (the manuscript copy of the letter I found dated it to 21 November 1699). For de Beer, November 1696 was an impossible date for Locke to have been in London. The second reason de Beer believed it was a fake was because Rebecca Collier and Rachel Breckon could not be traced in any extant Quaker records and their names also varied greatly between Quaker publications as Rebecca Collins and Rachel Buckon. It was also designated as spurious because the tone of the letter was inconsistent with Locke’s other writings.

Whilst conducting further research trips and archival searches, I uncovered five more copies of the letter. All of them bore the date of 21 November 1699. One of the copies was located at the Beinecke Library in Yale and one at the Quaker Library at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. The other copies were all found at Friends House in London. This suggested to me that there was something about this letter that was important for the 18th and 19th century Quaker community, who had come to copy, circulate and transcribe this letter. I started to consider whether I might be able to write something about the importance of the letter to the institutional memory of the movement. This was because even if the letter wasn’t genuine, it is clear that the Quakers who copied this letter believed that it was real. This was the real lightbulb moment for me in the project, as I now found a way of discussing the significance of the letter without having to worry about the question of its authenticity.

However, the evidence deepened following another research trip to Friends House, where (following a conversation with an archivist) I was able to locate Rebecca Collier through Quaker birth, marriage and death records. I was able to find the birth of a Rebecca Collier in 1668, and a marriage certificate documenting the marriage of Rebecca Collier to Emmanuel Proctor in 1709. Both events were registered to the parish of Selby in Yorkshire. If this was the right person, she would have been 31 when the letter from Locke was written.

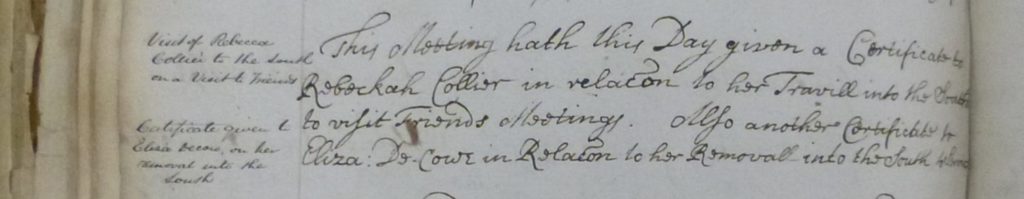

I decided to follow this lead up, as I now knew that a woman called Rebecca Collier had existed. I started to mine the Quaker meeting minutes for the monthly and quarterly Quaker meetings in Yorkshire to see if I could find any further record of Rebecca Collier’s career as a minister. This is because it was expected that most Quaker ministers would have registered their intent to travel with their local meeting.

I went through a large volume of Quaker meeting minutes held at the Brotherton Library in Leeds looking for references to Rebecca Collier, and found a request for a certificate to travel from a woman called Rebecca Collier, who wanted to travel to Quaker meetings in the South of England in July 1699. I also found a number of other references to her and the journey in other meeting records, including a certificate to travel.

Although no mention was made of her encounter with Locke, I now knew that a preacher called Rebecca Collier existed. More importantly, there was a strong probability that she was preaching in London at the time that this encounter with Locke was alleged to have taken place. I was also able to find her companion Rachel Brecken through a similar process – though this was a lot harder because there was so much variation in how Brecken was spelt. But I eventually found her records in the meeting minutes at Hull Archives, where she too had also requested a certificate from her local meeting of Whitby in Yorkshire to travel to London in the summer of 1699 to preach.

These were real revelations for me, as I could now quite concretely say that the Locke scholarship had got it wrong when they stated that Rebecca Collier and her companion were ‘wholly fictional’.[1] It also gave me ammunition to encourage a revision to the dating of the letter. And, on the recommendation of Mark Goldie, a leading expert on Locke, I was able to confirm from Board of Trade Minutes that Locke was present in London in the days before the 1699 letter was supposedly written.

Whilst I wanted to believe that this letter was genuine and that the encounter between Locke, Collier and Brecken had really happened, this all remained speculative. The final article that is due to be published in the English Historical Review on Locke and the debate over women’s preaching discusses the reception of Locke to the Quaker community in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It explores his importance as a biblical commentator, a facet of his published output that is largely overlooked by scholars of Locke. It questions why Quakers, who wished to separate from the world that surrounded them, invoked Locke so readily in their discussions on women’s preaching? What was it about Locke and his thought that made so many Quakers convinced that the letter was genuine and worthy of copying? And how did this letter and Locke’s legacy fit into broader debates about female preaching?

An unanswered question I have, is the issue of a potential Quaker forger. What would their motive have been? Indeed, if the letter were to have Quaker origins, this raises an intriguing problem, since this was a religious group that prided itself on its reputation for honesty and integrity in speech and action. Such an act of deceit would thus have seriously jeopardised the individual conscience of the forger and the claims to spiritual purity, and integrity that lay at the heart of Quaker theology.

The final article took many years to come to fruition. I made the discovery in 2012, and didn’t finish writing the article until 2021. In part, this was because I didn’t realise how ‘magical’ this source was until much later when I had follow-up conversations about the letter with colleagues and friends in the weeks, months, and years following the discovery. This process has also taught me the importance of perseverance and creativity: after discovering that the letter had been dismissed by the authorities of Locke as a fake, I started to pursue a different line of questioning about the motive of a Quaker forger, which enabled me to ask different questions of the source and brought me into dialogue with experts on Locke. Without this light bulb moment, I would not have uncovered further copies of the letter or been able to successful trace Rebecca Collier through the genealogical and meeting records, and thus made the intervention in Locke scholarship that I have been ultimately able to do.

[1] e.g. M. Goldie, ‘The Early Lives of John Locke’, Eighteenth-Century Thought, iii (2007), p. 61.