In order to assess counter-terrorism review in the UK, we first needed to map the extremely wide range of activities, institutions, actors, laws, and policies that fall under the umbrella term of ‘counter-terrorism’. This would allow us to identify the terrain on which we hoped to critically assess counter-terrorism review, as well as to identify review mechanisms that have scope to review counter-terrorism-related activities, even if not conventionally thought of as ‘counter-terrorism review mechanisms’.

Our starting point was the Government’s CONTEST strategy. Initially conceived in 2003, the policy only entered the public domain in 2006 and was intended to be a “pan-governmental” response to terrorism. It has four axes: Pursue, Prevent, Protect and Prepare. Prevent focuses on identifying potential terrorist plots and utilizing broad intelligence and surveillance powers to detect and stop persons who might be ‘vulnerable’ to developing terrorist ‘sympathies.’ Prevent generated continuing criticism. Pursue largely describes the Government’s prosecutorial policy. Protect seeks to minimize exposure and weakness to terror attacks by strengthening security, particularly at Borders and on the transport network. Prepare centres on mitigating the impact of an attack. These earlier versions produced polarized critique. Prevent disproportionately focused on the UK’s Muslim communities, interferes with liberty and conflicts with rights.

The 2011 version of CONTEST, which we used to begin our analysis, introduced annual reporting on each of the four axes, sought to outline a statutory basis for the PREVENT duties (which was achieved in the Counter Terrorism and Security Act 2015), shifted the focus of these preventative measures into ‘de-radicalisation’, expanding the PURSUE measures to focus on deportation with assurances, and extended special judicial procedures to facilitate the handling of “sensitive and secret material to serve the interests of both justice and national security.” (CONTEST 2011: 45)

The 2011 version of CONTEST, which we used to begin our analysis, introduced annual reporting on each of the four axes, sought to outline a statutory basis for the PREVENT duties (which was achieved in the Counter Terrorism and Security Act 2015), shifted the focus of these preventative measures into ‘de-radicalisation’, expanding the PURSUE measures to focus on deportation with assurances, and extended special judicial procedures to facilitate the handling of “sensitive and secret material to serve the interests of both justice and national security.” (CONTEST 2011: 45)

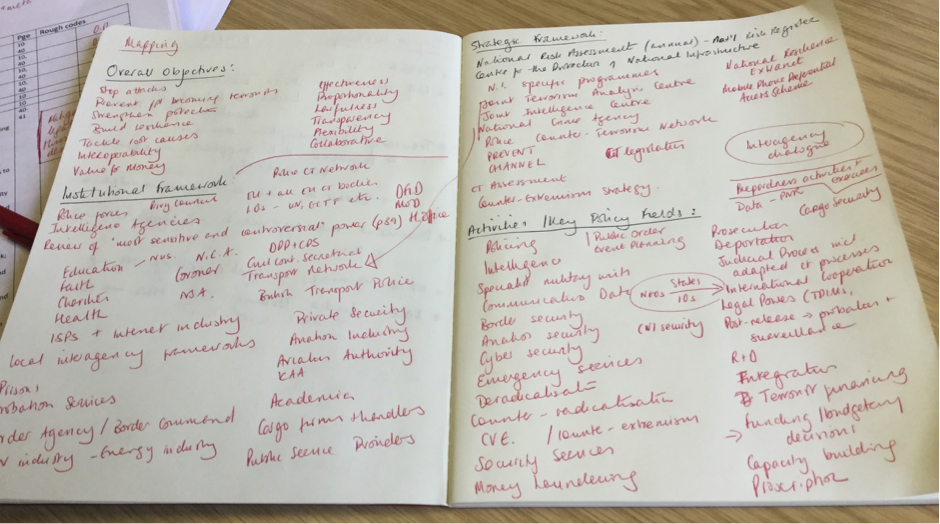

Working from this document, the subsequent annual reports, and commentary from the Joint Committee on Human Rights and the Home Affairs Committee, we could identify–initially in rough form as the image above shows, and later in more concrete and systematic ways– the (1) overall objectives, (2) institutional framework, (3) strategic framework, and (4) key policy and activity fields that make up counter-terrorism in the UK.

This made it clear that counter-terrorism extends across practically the entire remit of Government work and involves an extremely large range of institutions and practitioners, from the Security Services and the Police to schools, the NHS, the third sector and the travel industry. It goes well beyond the police, intelligence and security activity that we might most obviously see as being connected with counter-terrorism. This expanse creates a real challenge for understanding, mapping, knowing, critiquing, and reviewing counter-terrorism.

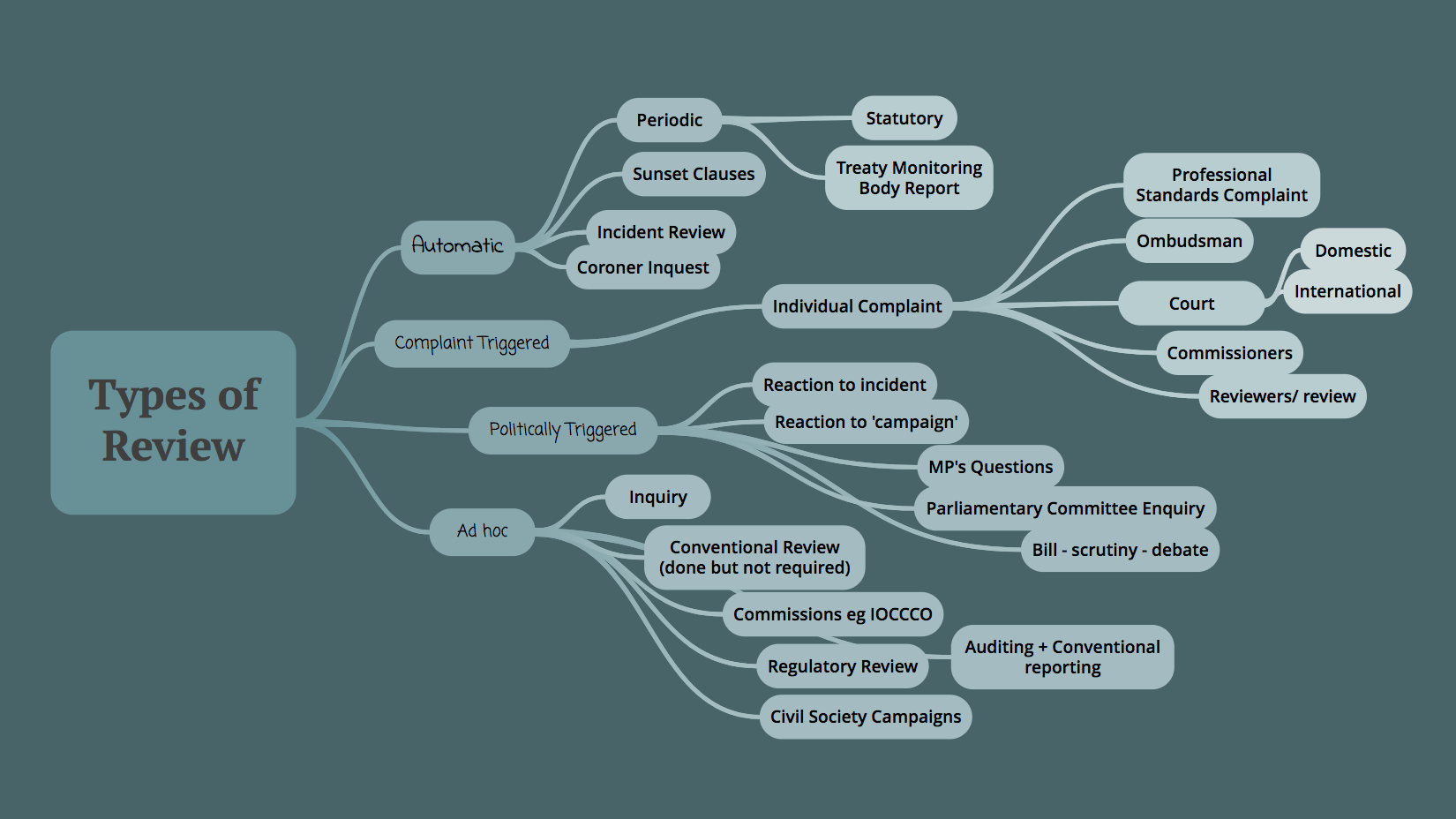

From the perspective of this project, it means that our starting points on who and what  might be said to constitute counter-terrorism review per se had to be multiple and wide ranging, as the diagram to the right hand side of this post begins to illustrate, and that key decisions about which review mechanisms to concentrate on—and how to understand and perhaps typologies these mechanism—became critical to the progression of the project. We will pick up on these decisions, and on mapping and understanding review mechanisms, in a future blog post.

might be said to constitute counter-terrorism review per se had to be multiple and wide ranging, as the diagram to the right hand side of this post begins to illustrate, and that key decisions about which review mechanisms to concentrate on—and how to understand and perhaps typologies these mechanism—became critical to the progression of the project. We will pick up on these decisions, and on mapping and understanding review mechanisms, in a future blog post.

Which strategic areas will the project specifically target e.g premised on religion, rights and law of best interest of citizenry, ethnography, high-level – risks counties etc . Prevention at all times is best, though the other axes are equally important because the terrorists also learn new ways….