In this blog, Lois Burke, explores how corpora of literary texts and specialised software to search through these corpora can enrich both literary and socio-cultural studies. Lois looks at ChiLit, GLARE’s 19th Century Children’s Literature Corpus, to find textual evidence in literary sources to support her research on children’s, and specifically girls’, magazine culture in Victorian England. As Lois’ blog shows, there are various ways of working with literary texts and using them as a source of historical information. It is a question to what extent literature can be used as a reliable historical source. In the GLARE project, we have been looking at various ways in which gender is represented in 19th century children’s books. One of our studies into ChiLit involved a detailed analysis of frequently mentioned occupations and their gender distribution.

A repeatedly mentioned occupation, as also shown in Lois’ blog, is ‘editor’. Lois’ analysis focuses on Alcott, Kipling and Nesbit, where children (both girls and boys) ‘play’ editors. However, all other mentions of editors in ChiLit show in a rather subtle way that once one is grown up, being an ‘editor’ is a man’s job, as Lois also points out in her analysis of Alcott.

It is interesting to note that the job of an ‘editor’ pops up in the texts fairly frequently (with over 75 occurrences in ChiLit), with similar frequencies as ‘poet’, ‘policeman’, ‘clerk’ or ‘sergeant’ – all occupations traditionally held by men. However, the really frequent occupations, with over 1000 occurrences are ‘captain’, ‘prince’ and ‘doctor’. All men again. The range of occupations for women is extremely limited: apart from frequently occurring ‘princesses’ and ‘queens’, women feature as ‘maids’, ‘nurses’, ‘governesses’ and ‘nannies’. Even this simple frequency analysis well supports existing scholarship on the limited roles of women in Victorian society. But now enjoy Lois’ more optimistic outlook for the future of girls – as ‘educated, sporty and socially active’.

Lois Burke is about to submit her PhD on late-Victorian girls’ manuscript writing and literary culture. She works closely with the Museum of Childhood in Edinburgh where she has co-curated several exhibitions. Her article on Victorian girls’ manuscript magazines is forthcoming in a special issue of Victorian Periodicals Review. She will be speaking about digitising Scottish children’s writings alongside Kate Simpson at the inaugural Scottish Early Literature for Children Initiative (SELCIE) conference held at the University of Edinburgh on November 23. She tweets @LoisMBurke.

***

The latter-part of the nineteenth century which witnessed the Golden Age of children’s literature also saw a blossoming of girlhood cultures. The ‘new girl’ was founded, who was educated, sporty, and socially active (Mitchell 1995). Her image was cultivated through the periodical press for young people, which encouraged reader participation. Correspondence pages and essay societies in magazines like Monthly Packet and Girl’s Own Paper valued and rewarded the voices of girl readers (Rodgers 2016, Moruzi 2012). Some young people recreated periodical culture by making their own manuscript magazines at home or in school. This peer writing culture was also depicted in fiction. In this post, I will detail how the CLiC app can help to uncover the presence of Victorian children’s writing cultures in Golden Age fiction.

Academic interest in children’s voices and agency in archival sources is reaching an exciting pace. Insights generated from digital humanities methods, sociological theories, as well as English Literature and History disciplinary knowledge is creating a new paradigm in this research area.

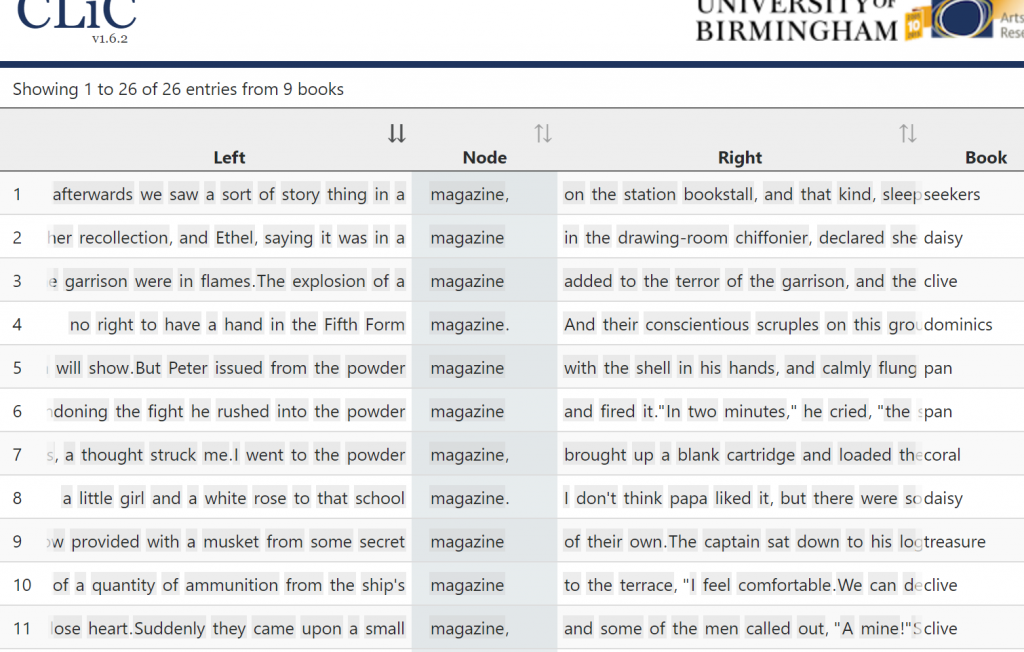

The CLiC interface has supplemented my research in this area. Searching for magazine, paper and manuscript has enhanced my search for the material manifestations and understandings of authorship in the Golden Age of children’s literature. The word magazine only occurs 26 times in the ChiLit reference corpus, compared to 683 entries from 59 books for the word paper. Comparing these examples adds to our understanding of Victorian children’s cultural engagement. They provide information about the different functions that manuscript magazine writing served in children’s fiction.

My search began with Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1879). In the novel, the four March sisters write the Pickwick Portfolio, a manuscript magazine in which each girl writes as a character from Dickens’ first novel. Importance is placed on the performance of the magazine production: ‘Jo, who revelled in pens and ink, was the editor. At seven o’clock the four members ascended to the clubroom.’ Each of the girls adopts a male pseudonym from Pickwick for their role in the paper. The girls’ tacit knowledge of the male tradition of magazine production is manifest in their gendered performance. But, in doing so, they create a uniquely girl-centered practice. This explains why, when Laurie Lawrence attempts to join one of their other societies, the ‘Busy Bee Society’, in which the girls practice their feminine accomplishments, they are reluctant to allow him to participate: ‘We should have asked you before, only we thought you wouldn’t care for such a girl’s game as this.’

This is also a wonderful example of the intertextuality and reflexivity of children’s fiction from this era. Alcott appropriates the idea of a Pickwick club, which were men’s clubs which sprouted following the publication of The Pickwick Papers in 1837 and then again following Dickens’ death in 1870. In my research into archival girls’ writings, I have found a real adaptation of the March sisters’ fictional Pickwick Portfolio in Eglantyne Jebb’s manuscript magazine Briarland Recorder, which is now held at the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics. Little Women is of course based on the real girlhood experiences of Louisa May Alcott and her family. This example goes to prove that children’s peer cultures spawned imitations, which were both influenced by literature and appropriated in it. It also depicts the complex negotiations taking place in both adult and child writers’ performance of gender and authorship.

This is also a wonderful example of the intertextuality and reflexivity of children’s fiction from this era. Alcott appropriates the idea of a Pickwick club, which were men’s clubs which sprouted following the publication of The Pickwick Papers in 1837 and then again following Dickens’ death in 1870. In my research into archival girls’ writings, I have found a real adaptation of the March sisters’ fictional Pickwick Portfolio in Eglantyne Jebb’s manuscript magazine Briarland Recorder, which is now held at the Women’s Library at the London School of Economics. Little Women is of course based on the real girlhood experiences of Louisa May Alcott and her family. This example goes to prove that children’s peer cultures spawned imitations, which were both influenced by literature and appropriated in it. It also depicts the complex negotiations taking place in both adult and child writers’ performance of gender and authorship.

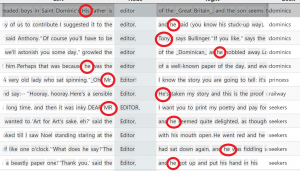

Results from the CLiC concordance search provide fascinating comparisons in Golden Age children’s literature. Mixed-gender magazine composition is explored in E. Nesbit’s The Treasure Seekers (1899). It tells the story of six siblings: Dora, Oswald, Dicky, Alice, Noel, and Horace Octavius Bastable. The children decide to help restore the fortunes of their impoverished father, and Noel manages to sell some of his poetry to a newspaper. Inspired by this, the children take it upon themselves to start a magazine of their own. But the desire for profit is soon overtaken by the negotiations of composition: ‘Everybody wanted to put in everything just as they liked, no matter how much room there was on the page. It was simply awful!’ The magazine is written up with a typewriter, and copies sent out to friends, so the children do not make money from their work as they initially hoped. Differences in gender, age and personality between the children create tensions: ‘Dora wanted to be editor and so did Oswald, but he gave way to her because she is a girl.’ Their contradictory voices are interwoven in the serial stories, and the magazine becomes a platform for dispute:

‘Come on, you valiant man and true, I’d like to have a set-to along of you!’ (That’s bad English.–ED. I don’t care; it’s what the dragon said. Who told you dragons didn’t talk bad English?–Noel.)

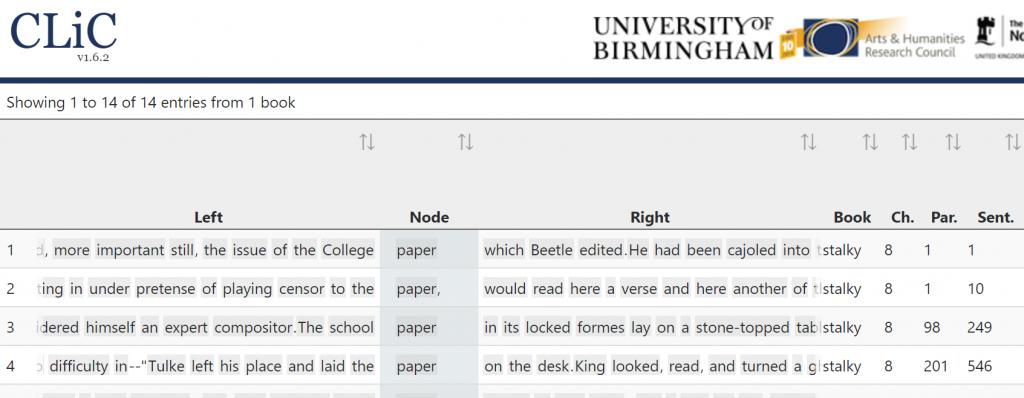

Boys’ school magazine making is depicted in Rudyard Kipling’s Stalky and Co. Also published in 1899, it is a collection of short stories set in a boys’ boarding school. The school boy Stalky names their school newspaper the Swillingford Patriot and his friend Beetle edits it. The space of the Head’s ‘tobacco-scented library’ is conductive to the boys’ manuscript culture: ‘There Beetle found a fat arm-chair, a silver inkstand, and unlimited pens and paper.’ The children’s ritual is encouraged by an older arbiter, the Head, who gives the boys free reign of his library, ‘prohibiting nothing, recommending nothing.’ Unlike the March sisters or the Bastable siblings, the pleasure and aspiration of youth composition is shared beyond their peer cultural group:

Then the Head, drifting in under pretense of playing censor to the paper, would read here a verse and here another of these poets, opening up avenues. And, slow breathing, with half-shut eyes above his cigar, would he speak of great men living, and journals, long dead, founded in their riotous youth; of years when all the planets were little new-lit stars trying to find their places in the uncaring void.

Although this writing culture is child-led, the example from Stalky and Co. demonstrates that adult pedagogy and socialisation were also major influences on youth composition. Recent studies have suggested that children’s culture manifests the tensions between adherence to socially-imposed structures, and the child’s individual tendency to challenge and subvert such limitations (see introduction in Jenkins 1998).

All three of these fictional examples place writing composition as an important aspect of the children’s creative development amongst their peers. Differing expectations of boys’ and girls’ conduct can be seen in each example, but a commonality is the complexity of collaboration and hierarchy for child writers. This is comparable with manuscript writing cultures of real Victorian children, which are continuing to be recovered from archives. The computer-assisted methods accessed through CLiC make a valuable contribution to this rich field of study.

Primary sources

Alcott, L. M. (2008). Little Women. London: Vintage.

Kipling, R. (2009). The Complete Stalky & Co. Oxford: Oxford World’s Classics.

Nesbit, E. (1995). The Story of The Treasure Seekers. London: Puffin.

References

Jenkins, H. (Ed.) (1998). The Children’s Culture Reader. New York: NYU Press.

Mitchell, S. (1995). The New Girl: Girls’ Culture, 1880-1915. New York: Columbia University Press.

Moruzi, K. (2012). Constructing Girlhood Through the Periodical Press, 1850-1915. Abingdon: Ashgate.

Rodgers, B. (2016). Adolescent Girlhood and Literary Culture at the Fin de Siècle: Daughters of Today. London: Palgrave.

Please cite this blog as follows: Burke, L. (2018, 24 September). Creating and recreating children’s manuscript magazine culture in Victorian fiction [Blog post]. Retrieved from: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/glareproject/2018/09/24/creating-and-recreating-childrens-manuscript-magazine-culture-in-victorian-fiction/.

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?