The Legal Recognition of Sign Languages (LRSL) project was Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions Individual Fellowship which ran from 2021 to 2014. The project was run by me, Dr Gearóidín McEvoy in Birmingham Law School.

LRSL looked at how legal recognition of sign languages impact Deaf people in Ireland, Finland and across the UK. The goal was to investigate how laws which purported to protect, promote or recognise signed languages actually impacted Deaf people and how those laws might be changed or improved to better serve the needs of the Deaf Community. LRSL then produced a ‘roadmap’ for effective legislation for signed language recognition, based on the findings of the research. This roadmap shows what Deaf people need and want, based on their own assertions, and shows how those needs and wants can be included in laws which aim to serve the Deaf Community.

At the outset, it is important to provide some preliminary context, as awareness of the Deaf Community is not widespread. First, not all signed languages are the same. In the three countries studied for this work, there are four main signed languages in use, with dialectal variations in the same way that might be observed in spoken languages. Those languages are: Irish Sign Language (ISL), primarily used on the island of Ireland; British Sign Language (BSL), used throughout the UK and in Northern Ireland along with ISL; Finnish Sign Language (FinnSL), the most widely used sign language in Finland; and Finland Swedish Sign Language (FinnSSL), a minority signed language used in Finland. Each sign language is different, and they are not signed versions of spoken languages. For example, while the dominant spoken language in Ireland and the UK is English, BSL and ISL are vastly different to one another.

Secondly, although signed languages can be learned by anyone, not all Deaf people have access to learning a signed language. Most Deaf people are not born to Deaf parents (in fact, it is suggested that 90% of Deaf people grow up in otherwise hearing families). Those families are unlikely to know a signed language prior to the arrival of a Deaf child. Additionally, the legacy of a mistaken and now widely disproven belief that signing would inhibit a child’s ability to acquire spoken language and should therefore be dissuaded persists. Children are often prevented from learning a signed language and their parents are often advised (sometimes by medical professionals) against exposing their child to a signed language. Sign language medium schools are increasingly closing, and children are not given the opportunity to be surrounded by a linguistically appropriate language. Learning a signed language is a way to ensure a child does not experience language deprivation. Learning a signed language gives a child the tools to learn other languages, including spoken languages, in the same way that a hearing child might learn an additional language.

Thirdly, Deaf people make up Deaf Communities which are vibrant, cultural and linguistic groups. While Deaf people might not be connected by geography, ethnicity or race in the same way that many minority groups might be, they are connected by their shared experience of being Deaf in a largely hearing society. (Although, being Deaf can mean many different things: being born Deaf, becoming Deaf as a child, or teenager, becoming Deaf in adulthood, being hard of hearing, wearing a cochlear implant or hearing aid, communicating via spoken language, signed language, or a mixture of both, etc.)

LRSL collected empirical data from Ireland, Finland and the UK through semi structured interviews with Deaf people in each jurisdiction. Twenty-eight interviews were conducted with Deaf activists, community leaders, professionals, and general members of the Deaf Community. Interviews were largely conducted online and in the signed language of the participants choice and interpreted with a registered interpreter of their choice. Interviews were conducted in English, ISL, BSL and FinnSL. Interviewees were asked about their experiences under laws which purport to protect sign language in their respective jurisdictions and how they felt that laws or systems could be improved for the betterment of Deaf people.

At the time of the project, Ireland had passed the Irish Sign Language Act in 2017, and Finland had passed the Sign Language Act in 2015 after constitutional recognition of signed language in 1995. In the UK, Scotland had passed the British Sign Language (Scotland) Act in 2015 and the British Sign Language Act in England and Wales passed during the project, in 2022. Many interviews with British Deaf people were conducted in the time immediately after the passing of that Act. At the time of the research no sign language law had yet been passed in Northern Ireland, although there are plans for the passing of a law to recognise BSL and ISL.

Although the research spanned three countries, with different legal systems, different histories and different Deaf Communities, many experiences from interview participants were similar. A common finding from the research was that participants were generally disappointed with the laws which had been passed. There was a feeling that the Deaf Community had been promised that the laws would change their lives, improve their lives and give greater opportunities, but that this had not materialised, or could not materialise.

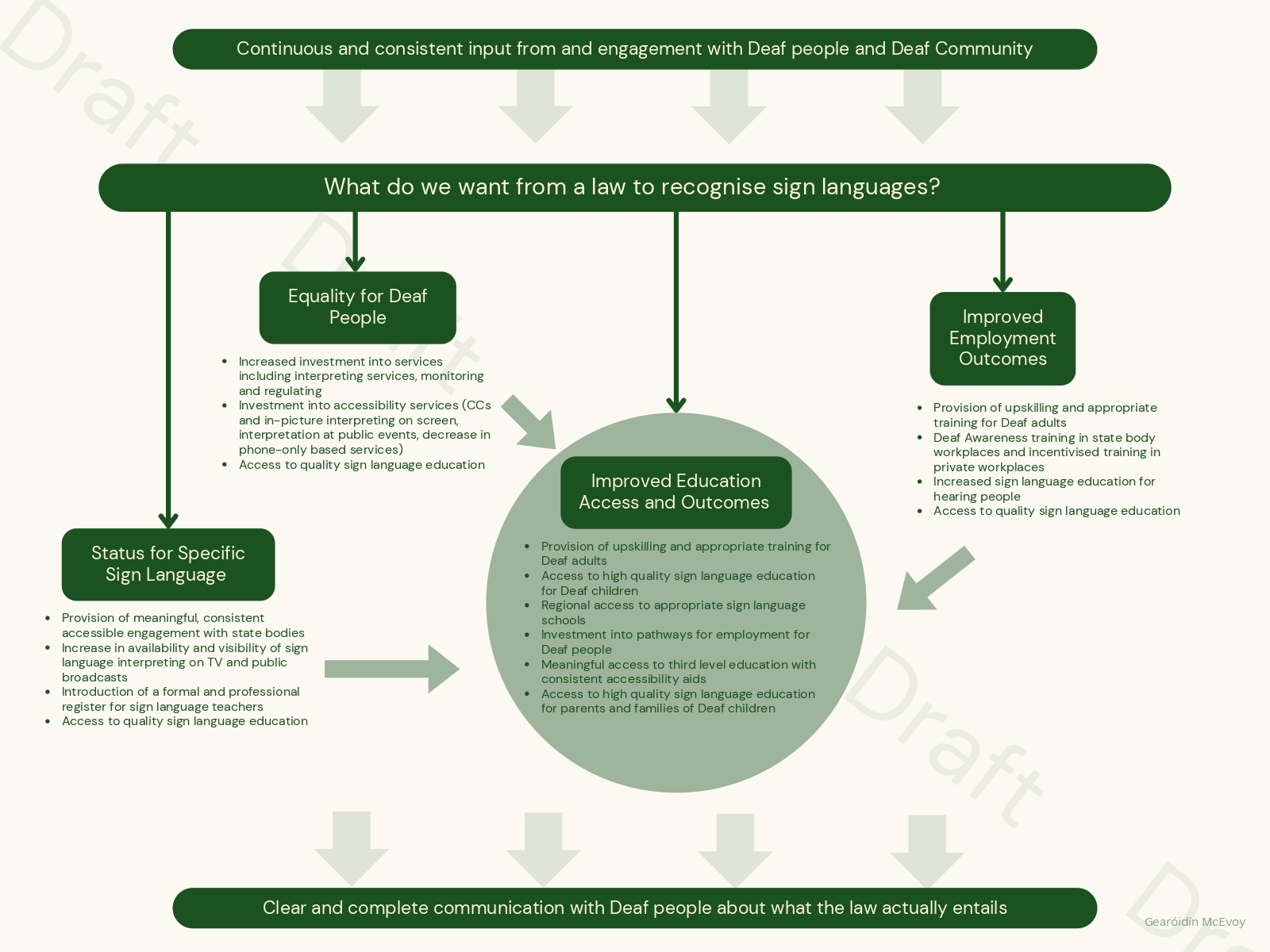

Each interviewee was asked if they could change the law or introduce a new law, what would that law look like. The responses show the needs and wants of Deaf Communities and have been catalogued into a roadmap for effective legal recognition of sign languages.

At the outset, Deaf people must be involved in the creation of laws. There needs to be meaningful, consistent and engaged input from the Deaf Community. The communication between legislature and the Deaf Community must be two-way and accessible. If Deaf people are involved, they can highlight their needs and experiences, and it can help to communicate to the Community the scope of the law when it is passed and manage expectation.

There were four main themes for what people wanted the law to guarantee which emerged in the data. First, people wanted the law to grant specific status to signed language. This was particularly true in those states where a spoken language had a specific and identifiable legal protection, such as spoke Irish in Ireland, Swedish in Finland, Welsh in Wales or Gaelic in Scotland. Participants wanted the provision of meaningful, consistent and accessible engagement with state bodies, an increased availability of sign language interpreting on TV and public broadcasts, and the introduction of a formal register for sign language teaching.

Secondly, participants wanted the laws to ensure equality for Deaf people. Specifically, this would mean increased investment into services including interpreting services, monitoring and regulation. It would mean investment into accessibility services, such as closed captioning, in-picture interpreting on screen, interpretation at public events and the decrease in phone-only based services. Not all Deaf people are sign language users and so it is important, when improving equality, to consider the communication needs of the wider Deaf community.

Third, and building on the improvement in equality, participants wished that the law would help to improve employment outcomes for Deaf people. Unemployment in the Deaf Community is a chronic problem globally, and laws designed to uplift the Community ought to address this need. In doing so, laws designed to improve employment outcomes ought to provide upskilling and appropriate training of Deaf adults, many of whom have been denied equitable access to education in their youth and are at a disadvantage in the workforce. There should be the provision of Deaf Awareness training in state body workplaces and incentivised training in private workplaces to normalise Deaf people in the workplace for hearing colleagues. Additionally, efforts should be made to improve the access to sign language education for hearing people, to aid in communication with the Deaf community and normalise the use of sign language in everyday life.

Finally, and most importantly, participants wanted the law to improve education access and outcomes for Deaf people. Overwhelmingly, education was the major concern for most interviewees, with 23 of 28 participants referencing education. Deaf people across the world are denied access to education. The majority of Deaf people globally have no access to education, and even where access to education is provided, it is often not fit-for-purpose for the specific needs of Deaf people. Overwhelmingly, participants to this research wanted improved access to sign language education – that is, schools which operate through the medium of signed language, where Deaf children attend with other Deaf children and develop community. This is opposed to mainstream education, where Deaf children will attend an otherwise hearing school where adjustments are provided. No participant wished for Deaf children to be provided with improved access to mainstream education, and in fact many participants who had themselves attended mainstream education were critical of this as a solution to educating Deaf children. If laws for recognising signed language are to provide for improved education access and outcomes, then there most be meaningful access to high quality sign language education for Deaf children. This access must be available regionally, so that children are not in a ‘post code lottery’ where their access to quality education is determined by their accident of their geographical location. There must be provision of early intervention access to signed language, and the provision of daycare and preschool options for Deaf children so that they may have meaningful access to signed language at the critical age group between 0-5. There must be investment into pathways for employment for Deaf people, and as above, provision of upskilling and appropriate training for Deaf adults. There must be meaningful access to third level education with consistent accessibility measures provided as standard. There must also be access to high quality sign language education for parents and families of Deaf children, so that communication in the home can be assured. From the research it was clear that education access is the singularly most important issue to Deaf people and without investment into education, the other three themes cannot be assured. Assuring legal status for a signed language, when the Deaf Community is deprived of meaningful opportunities to learn sign language renders the status tokenistic and hollow. Assurance of equality cannot be guaranteed for Deaf people in the absence of equal access to education and meaningful opportunities. Without equal access to education, Deaf people are inherently disadvantaged by lack of opportunity in the workplace. Education is the key to the achievement of all other aims under the findings of this research.

Once legislation has been passed, or is in the process of passing, it is vital that there is clear, complete and accessible communication with the Deaf Community regarding the scope of the act. It is vital that people are aware of any changes to systems, new entitlements, new rights and how to engage those systems, entitlements or rights, prior to the passing of the law.

To conclude, LRSL investigated the status of legal recognition of signed languages in Ireland, Finland and the UK. Moving forward, the findings of LRSL can inform lobby groups, activists, politicians, legislators and Deaf Communities about what aspect of laws work, what do not work, and what are the goals of Deaf people in legislation purporting to protect the Deaf Community and signed languages.