A thirteen-year-old boy sitting at the back thrusts immediately his hand in the air. It is the end of a two-hour Year 9 workshop on eighteenth-century letters. The final task has been a creative writing exercise. The young people have been invited to write a letter in the voice of Hampton Allen, using early-eighteenth-century language, and drawing on what they have learned in the workshop about women’s lives in this period. I have warned them that I will ask if anyone wants to read their letter out to the class. Myself and my colleague from the National Literacy Trust – Kyle Turakhia – fully expect zero volunteers. But several hands go up before I have finished the sentence, ‘So – would anyone like to read out their letter to the group?’. The boy begins, speaking in the imagined voice of Hampton:

Dear Fate,

I am writing this letter searching for forgiveness. Now that my dear husband has died, I have been terribly lonely …

When we began the Leverhulme project, ‘Material Identities, Social Bodies’, I knew about the impacts that eighteenth-century letters could have on us today. I wrote about this in our first blog post, ‘What Letters Did, What Letters Do’ (May 2021). This semester I have been exploring this further with a series of public engagement activities. This included a series of workshops at primary and senior schools in Birmingham, and with the Birmingham Adult Education Service. This blog post, written as these activities came to an end, shares some of my immediate reflections on these workshops.

The public engagement undertaken through the workshops conforms to what the UKRI calls ‘Open Innovation’, designed to ‘excite, inspire and involve people’ in my research.[1] Though I led on the content, structure, delivery and intended aims, there was a significant element of co-production: the schools’ and adult learner workshops were designed with input from teachers, tutors and Kyle from the NLT. As suggested in the UKRI’s guidance on engaging young people, I designed the schools’ workshops having researched the relevant schools’ curricula (in both English and History).[2] After an initial pilot, and in response to teacher feedback, a single primary school workshop was spilt into two – one KS2 Year 3-4 History & Letters workshop, and one KS2 Year 5-6 Literacy & letters workshop. In the case of the BAES adult workshops, I liaised with the subject leader on the module in which my workshops would sit and responded to interim feedback from learners and tutors during the six-week programme of workshops.

Co-produced, then, but this was not co-produced research.[3] Instead, the activity sat in between ‘a model of public engagement in which academic researchers disseminate their findings to those beyond the academy’ and ‘attempting to produce research with individuals and groups from different backgrounds and communities’.[4] I was neither primarily aiming to disseminate my research nor to produce research, though both things might take place. Instead, I was seeking to participate in a two-way process in which participants benefitted from new skills and insights about the present and the past, and I gained new insights about the historical material, its interpretation and its relevance today. This accords closely with the general definition of public engagement employed by the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement, which has ‘mutual benefit’ at its heart.[5] This kind of mutually beneficially public engagement, grounded in dialogue, both exceeds ‘dissemination’ and produces effects that fall outside my historian’s definition of ‘research’.

All the workshops were exhilarating. I found the adult education workshops particularly affecting. These were part of the English language module, ‘All About Me’. The series of three workshops, delivered to three separate groups, used eighteenth-century letters to think about the experiences of different people – young and old, men and women – across the life-course. They were intended to introduce the learners to new vocabulary, extend their knowledge of the English language and provide engaging opportunities to speak and write in English. With their irregular spelling, missing punctuation and unfamiliar vocabulary, eighteenth-century letters provide plenty of material for language learning. And in each workshop, there were opportunities to ‘correct’ the text, to explore unfamiliar words and to discuss alternative terms that we might use more readily today. So, a description of a young woman as ‘perverse & headstrong’ in one letter, was changed by learners to ‘irrational and reckless’.

But the bread and butter of these adult workshops was to talk about the letters – their context, character and stories – and to then talk about ourselves. Discussion lurched from smile-inducing anecdotes, to personal revelations that stopped me in my tracks. One exercise in the workshop on health advice in letters was to discuss the question, ‘Do you have any special medicinal remedies or practices in your family?’. Learners – young and old, from the UK, Europe, the Middle East and Indian subcontinent, including a pharmacist and an award-winning poet – happily shared recipes for garlic, yoghurt, honey, turmeric with milk or eggs, and rosehip tea. In contrast, discussing a letter from 1699 in which a father wrote advice to his 18-year-old son who was poised to move from the family home in Ireland to Bordeaux in France, one learner was visibly moved to share her experience of leaving her parents in Hong Kong only a few months before: she was not sure she would ever see them again.

Though I hope I responded with kindness and sympathy, I was not properly prepared for this sort of conversation. More importantly, I had not properly prepared the learners. This became clear to me during an inspiring roundtable on ‘Collaborative Public History’ organized by the Birmingham Research Institute for History and Cultures, where several of the speakers raised issues around safety, for researchers and participants. ‘[T]o genuinely care for an audience it isn’t enough just to say so, it has to be woven into the fabric of the piece’, Jessica Hammett, Ellie Harrison and Laura King say of collaborative public history.[6] The group of learners I worked with already knew one another, were in a familiar space, and had their regular tutor on hand. But next time around, care for the learners will be addressed at the start and throughout the workshops with clear signposting of upcoming issues and the many ways that learners might respond if they wish (including signalling upset or leaving the room).

In the adult workshops, the most successfully engaging aspect of the letters turned out to be the stories. Letters are a dialogic form which address a reader (the recipient) directly and in the first-person. Working with letters exemplifies what Erin Goheen Glanville has termed ‘reading as listening’.[7] Written in the first-person, they invite us to consider the motivations, experiences and mental world of a single speaker. This pull towards the human and affective aspects of a story might invite a ‘flattening out’ of the differences between past and present, as generalized ideas about human nature, character and emotion could come into play. Yet the Year 9 young people and adult learners were attune to the context of each eighteenth-century story and the differences between their society and those of the letter writers were exposed. Interpretations of the writer’s emotions were grounded in the text: ‘How is Thomas feeling?’ in the Year 9 worksheet was accompanied by the instruction, ‘Quotes from the letter to support my point’. My clear impression was that the participants knew very well that the people who had written these letters were not like them.

At the same time, similarities between dead writers and living readers emerged: between the authority of older brothers over younger sisters in a Polish family and in an eighteenth-century family of solicitors, between the importance of women’s domestic medical knowledge in a British Pakistani community and an eighteenth-century family of wine merchants. These discussions exposed yet more differences – those among the diverse group of people in the room – which we gifted and received in the form of our own personal stories. The generosity of the participants was staggering. Had this been a larger-scale programme, I would have used a combination of methods through which, as my colleague Faye Sayer has demonstrated, such well-being impacts of engagement projects can be robustly measured. Yet in conversation with the participants and learners, the ‘social well-being impacts’ of these workshops seemed evident to me: ‘team-working’, ‘forming relationships and making friends and breaking down barriers’ and ‘developing a sense of community’.[8] I don’t know what happened to these effects after each group dispersed, of course, though most returned for all three workshops. Perhaps they rapidly dissolved, though I suspect relationships and friendships built upon the exchange of personal memories tend to be more resilient than this. The longevity of impact is harder to measure, but I intend to return to some of these groups in the spring of 2023 to ask them.

Of all the workshops, those for KS2 focussed most explicitly on knowledge and skills. Using the letters of the children, Margaret and James, of the engineer James Watt, from The Library of Birmingham the classes discussed the different educational experiences of girls and boys. Comparing letters between children with a letter from Elizabeth Sancho, daughter of Ignatius Sancho and the only Black woman currently in our database (from the British Library), to her father’s patron, we explored how the choices children made regarding content and style depended on the identity of the correspondent – and therefore relations of power. The children practised signatures using an eighteenth-century manual of penmanship, recreated a folder eighteenth-century letter and then wrote formal letters of their own.

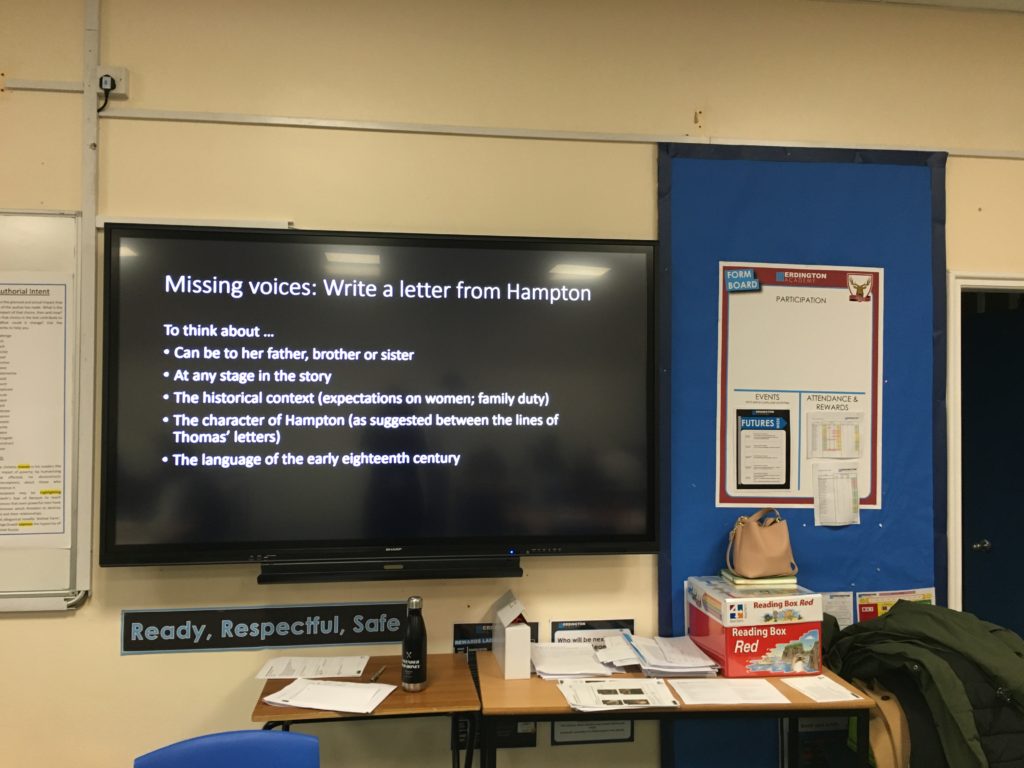

In contrast, stories shaped the Year 9 workshop. The class had followed the story of Hampton Allen through the surviving letters of her brother, Thomas. His disapproving letters charted his sister’s ill-advised courtships, her imprudent behaviour, and communicated their father’s threats to disinherit his daughter. Some of these letters, from Derbyshire Record Office are now accessible in our public database. The kids used a series of Thomas’ short letters to reconstruct events, exploring the motivations and feelings of the protagonists throughout. Yet one voice remained absent – that of Hampton herself. No longer! I now have 19 letters from Hampton Allen in my possession, the product of those Year 9s. I can tell you that she wrote rather short, formal letters, in a curious mix of early-eighteenth- and early-twentieth-century English. What strikes me most about these letters is the attempt by the authors to stick close to the historical information they had heard and to frame their writing in what they had identified as eighteenth-century style. A creative writing exercise, to be sure. But one in which the authors strove to imagine the mental world of this historical woman. ‘I was just too much in love’. ‘I could not stop thinking about how I went against your command’. ‘I don’t want our family’s reputation to go down even more’. ‘I know now that you, brother, were trying to protect me’.

Eighteenth-century letters – challenging as they might at first appear to non-experts – nevertheless have the potential to inspire conversation, writing, language literacy, historical imagination and historical literacy. This is why we are delighted to have launched the first edition of the public database of eighteenth-century letters (on Monday 5 December) and to have run a ‘transcribathon’ (on Wednesday 7 December), both supported by a campaign on Twitter and Tiktok.[9] We have started to find new and – we hope – productive ways to use this corpus, in addition to our academic research. In making more of these letters available, we hope others find new uses for them, too.

[1] https://www.ukri.org/what-we-offer/public-engagement/guidance-on-engaging-the-public-with-your-research/

[2] ‘Engaging Young People with Cutting Edge Research: a guide for researchers and teachers’ (RCUK, March 2010).

https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/UKRI-151020-EngagingYoungPeopleWithCuttingEdgeResearch.pdf. See also the guidance at the National Co-ordinating Centre for Public Engagement: https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/do-engagement/partnership-working/working-with-schools

[3] For a useful guide to co-produced research see Jude Hutchen and Annie Oliver, ‘Aiming Towards Successful Co-Produced Research. From a Community Perspective’ (Wellspring, AHRC, University of Bristol): https://cpb-eu-w2.wpmucdn.com/blogs.bristol.ac.uk/dist/7/542/files/2021/10/Coproduced-Research-for-Communities-web.pdf

[4] Margot Finn and Kate Smith, ‘Introduction’, New Paths to Public History (Palgrave, 2015), p. 2.

[5] https://www.publicengagement.ac.uk/about-engagement/what-public-engagement

[6] Jessica Hammett, Ellie Harrison, Laura King, Art, ‘Collaboration and Multi-Sensory Approaches in Public Microhistory: Journey with Absent Friends’, History Workshop Journal, Volume 89, Spring 2020, Pages 246–269, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbaa010

[7] Erin Goheen Glanville, ‘What Happens to a Story? En/countering Imaginative Humanitarian Ethnography in the Classroom’, in Céline Cantat, Ian M. Cook, Prem Kumar Rajaram (eds), Opening Up the University: Teaching and Learning with Refugees (eds.) (Berghahn Books, 2022),p. 311. https://doi.org/10.3167/9781800733114

[8] Faye Sayer, ‘Understanding Well-Being: A Mechanism for Measuring the Impact of Heritage Practice on Well-Being’, in Angela M. Labrador, and Neil Asher Silberman (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Public Heritage Theory and Practice, Oxford Handbooks (2018; online edn, Oxford Academic, 11 Jan. 2018), https://doi-org.bham-ezproxy.idm.oclc.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190676315.013.21,

accessed 9 Dec. 2022.

[9] The transcription facility on the website will remain open indefinitely. These digital aspects of the project will be the subject of a future blog.