Lulu writes:

I was very lucky to get work experience at UoB’s History department in June 2023, and as part of my time with Professor Karen Harvey I spent a day transcribing and analysing 18th and 19th century letters. She’d chosen a variety of letters written by children and young people for me, such as those written on behalf of a sweet (but very chatty) young child Dorothy Nicholson rambling to her father about her day. But it was a letter from a 19-year-old Esther Wood writing to her friend Mary Anne in the autumn of 1811 that particularly caught my eye, and which I’ve included the transcription of here:

Manchester Oct 27th 1811

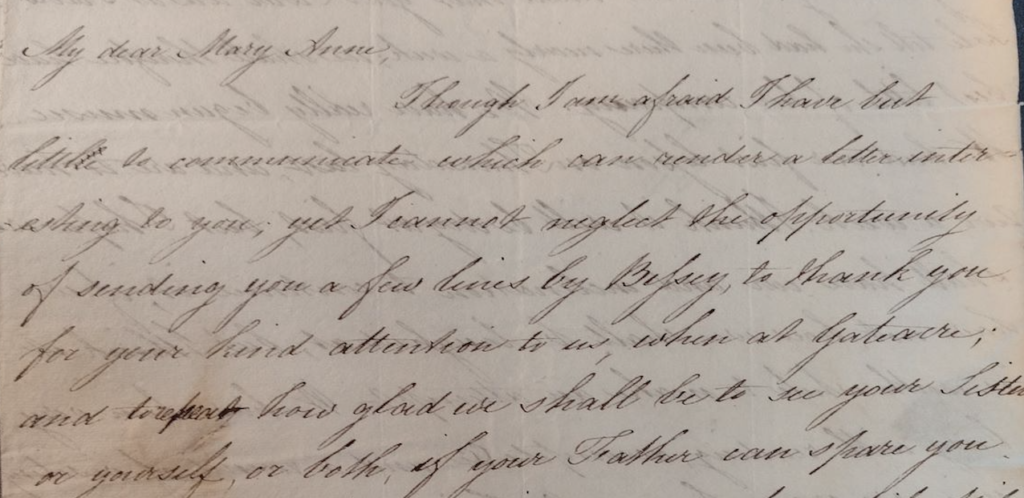

My dear Mary Anne,

Though I am afraid I have but little to communicate which can render a letter interesting to you; yet I cannot neglect the opportunity of sending you a few lines by Bessey, to thank you for your kind attention to us, when at Gateacre; and to repeat how glad we shall be to see your sister or yourself, or both, if your Father can spare you. I hope it will be convenient to you; when Miss Mills visits us, and I am sorry I cannot now say when that will be, as the Millses had friends with them, when we left Liverpool, and were to write to inform {^us} of the time as soon as they could fix it. If you cannot come when Miss Mills does we shall look forward to the pleasure of seeing you some other time.

I hope you were no worse for Mr Shepperd’s dance. On the following day we enjoyed ourselves very much, at Dr {?Jardina’s}, where we danced instead of playing at cards. You remember Mary {?Jardina} who is a lively pleasant girl. Unfortunately we did not know that your Sister was at Travis but till she had been there nearly a week; we shall therefore have but little of her company. We have really begun music. We had our first lesson on Thursday last, but I hope we shall have ear and inclination to continue it; if we have not, how we shall be laughed at, but I think it is worth while to make an attempt. We have been very busy with reading, accounts and a round of visiting since we came home. On Friday we were much gratified with an exhibition of the progress which the boys in the Lancasterian school had made in a short time. A number of them were in the dancing room of the Exchange and {^went} through their different occupations with astonishing alacrity. It is indeed wonderful what system and regularity will do – Mary joins me in love to Dorothy and yourself, and believe me to be, my dear Mary Anne,

yours sincerely

Esther Wood

[letter in the collection of the John Rylands Research Institute and Library, The University of Manchester]

What struck me reading Esther Wood’s letter to Mary Anne was not the obvious differences in the language Esther employs from my modern writing, but the similarities I could draw between Esther’s life, interests and complaints and my own. “We have really begun music…I think it will be very dry at first,” Esther writes, and immediately I am reminded of my best friend’s complaints about how boring she finds her piano lessons. It’s hard not to laugh, too, when Esther makes it a point to tell Mary Anne how impressed she was with the “boys in the Lancasterian school” on a recent visit – “we were much gratified with an exhibition of the progress”, she says. You could interpret her decision to devote a good portion of the letter to her account of these boys in various ways; having attended a girls’ school for the past five years, though, it’s all too easy for me to imagine a teenage Esther’s giddy excitement at these schoolboys, or her rushing home, full of animation, to write to Mary Anne about her time with them. Sweetly, Esther signs her letter “believe me to be, my dear Mary Anne, yours sincerely”. It’s a sort of declaration of close female friendship that makes me smile upon transcribing it and reminds me of how I sign birthday cards to my friends in a similarly affectionate way.

It feels, in an odd way, rude not to think about a possible response to Esther’s letter, though I have little information about either girl except that provided in Esther’s own words. There’s something touching about Esther’s listing of her everyday activities, and her insistence that her correspondent come visit her soon, that compels me to think of Mary Ann’s possible reply:

My dear Esther,

I am afraid I cannot write you a long letter, for our dearest Dorothy is clamouring to write her father and demands my attention – and yet I could not neglect your kind words. How lovely it is to hear of the Lancasterian school boys and their progress; please do write to me more of their different occupations, for I rarely can visit such schools at present. Mary Jardina is indeed a pleasant girl, and I am glad to hear of your wonderful time dancing with her family. I am also glad to hear of your music, though I hope you will continue even if you have little inclination for it; piano playing is such a wonderful skill. I too have been busy with reading and accounts, and a little sewing, though perhaps not as much as I ought, for family matters rather demand my time at present. My sister returned to Gateacre Sunday last and informed me of her short visit to you – how jealous I am that she could be in such lovely company as you and your family, whilst I was home all day minding dear Dorothy! Please do not fret about the Millses and myself; they often seem to be with friends, and I do not wish to impose. I look forward to our next visit anyway, or yours to Gateacre, for I have so much to tell you of – until then, Dorothy wishes you and Mary love, and so do I, my dearest Esther, for I am always

yours sincerely

Mary Anne

In Professor Karen’s last blog post she wrote about how “eighteenth century letters…have the potential to inspire conversation, language literacy, historical imagination and historical literacy” in the non-experts that read them. I’d extend on that and say that for me, as a 16-year-old girl living in an entirely different place and period to Esther Wood, engaging in her writing and creatively responding to it also allowed me to delve deeper into modern questions about female friendship and identity, and the ways in which we connect with our past. E.H Carr called history “an unending dialogue between the present and the past” and this idea of a “dialogue” between past and present feels especially pertinent when it comes to letter writing; in responding to Esther Wood’s letter, I felt myself almost literally engaging in conversation with its author, transcending the many years between us to share in the typical complaints and interests of a teenage girl that she discusses in her writing to Mary Anne.

It was a wonderful experience to be able to spend a day transcribing 18th and 19th century letters, and I’m so grateful to the History department at UoB for the opportunity to do so. More than solidifying my love for history, however, looking at these letters made me consider how such archival material provides both an intimate and unrivalled insight into somebody’s life and a space for reflection on our own. Transcribing and reflecting on Esther’s letter, for example, was a way in which I could not only ascertain basic information about her, but also connect with this nineteenth-century teenage girl – or, rather, a preservation of her in letter form – and relate to her emotions, her complaints, her life situation.

Looking at these letters made me reflect, too, on how communication has evolved since Esther’s time. I don’t think I’ve ever sent a written letter to my friends, yet perhaps my use of social media and text messages have become, in a sense, an archive of their own right; a digital record of who I am and what interests me. It’s fascinating to think about how communication will continue to evolve and how historians, young people and family members might find out about their own past when our present has become part of their history. Would a teenage girl two hundred years from now be able to see herself, or aspects of her life, in my own ‘digital archive’, just as I can in Esther Wood’s letter? It’s a comforting thought to think she would.

By Lulu F.