All images have been reproduced with kind permission of © British Library Board

The past few weeks have seen the reopening of archives and libraries across the country, and, happily for the project team, the opportunity to be reunited with the eighteenth-century letters at the heart of our research. But with archive slots in high demand, and with volumes and volumes of correspondence to look through, my approach to these archive visits has been more photograph-heavy than it might ordinarily have been. I open a volume, skim through a few letters to check that they are relevant in content, and then snap, snap, snap away with my camera.

When collecting photographs of as many relevant manuscripts as possible, there’s often not time to read each letter in detail in the archive itself. In a photographic daze, with pages and pages of beautiful, but often similarly stylised handwriting, not many things from the text of the letters themselves jump out at me. But my attention is captured by other features of the letters: pictures. Faces. Eyes. Feet. Mouths. Hearts. Noses. Stomachs. Ears. Dozens of ink or pencil sketches of body parts. And it is on these occasions that I stop in my tracks, keen to find out more about these dismembered body parts and why they had been so carefully sketched out and incorporated into familiar letters.

In some examples, writers—children and adults—include these drawings to practise or show off their life-drawing skills. This is apparent in a letter from Richard Dennison Cumberland (then aged 22) to his younger brother George (aged 20) in 1774. At the bottom of this page of pencil sketches of facial features—eyes (open and closed) mouths, and a nose—the artist writes: ‘I find the mouth most difficult to draw as you will perceive. It is a very bad one but have not time to mend it tho scarce know what it looks like’.[1] Richard goes on to apologise for not following his brother’s earlier artistic advice: ‘I am almost asham’d to confess how little I have practised the instructions you sent me’. Exchanging drawings, as well as letters, connects the brothers through their shared hobby, and allows George to offer direct artistic encouragement. Richard does not say who these striking disembodied facial features belong to. He does not mention any formal life drawing class – could these be sketches of the eyes, noses, and mouths, of members of the Cumberland household? Would George be familiar with these facial features, carefully pencilled out and sent through the post, and agree with Richard’s suggestion that the mouth was not a good likeness?

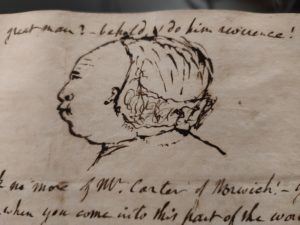

In other letters, cartoonish sketches of faces, often in profile, illustrate and add depth to textual descriptions of people’s appearance and characteristics. A 1764 letter from Thomas Twining to his brother Daniel includes an unflattering sketch of the ‘great man’ under discussion, complete with an overly elongated skull, capacious forehead, small facial features and a wayward left ear, captioned with the directive ‘behold, do him reverence!’[2] A year later Thomas sends his brother a similarly unbecoming cartoon of a nameless man, this time scribbled on to the letter wrapper. This second man is entirely lacking in forehead, and features a snub nose and a prominent chin. He has no apparent link to the content of the letter. What is the significance of his appearance on the letter wrapper, next to the address? Is it a portrait of Thomas himself, or perhaps his brother?

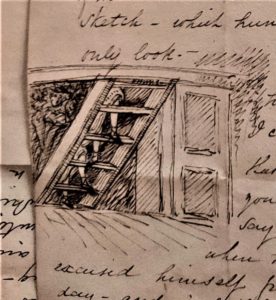

Other body parts appear for slightly different illustrative purposes. Disembodied legs feature in an 1828 letter from Thomas Clift to his mother. Two pairs of female legs, from the knee downwards, stockinged and shoed and with a tantalising hint of skirt, are depicted walking up a staircase. Thomas writes, in an excited tone that doesn’t map easily onto an exchange between mother and son:

there were the greatest number of pretty girls and Eligant women I ever saw at one time – and really when I think of all the little feet, the prettily turned ankles […] I can’t go on for blushing – the heat of my blushes has quite turned the paper – already – only see – and you know there are such queer sort of stair cases (they were indeed stare-cases) on board ship – called companion ladders &c – that it was actually no fault of mine that I am enabled to make the annexed sketch – which hundreds would vouch for as to accuracy, only look.[3]

Next to this voyeuristic and slightly unsettling passage, Clift is compelled to sketch out an impression of the legs and feet that so caught his attention. ‘Only look’, he urges his mother – the ink sketch a means of conveying what he feels words alone could not.

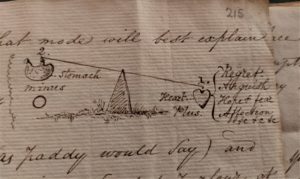

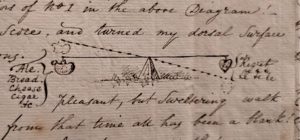

In another letter from the same family, the surgeon and illustrator William Clift sketches body parts to convey not what he sees, but how walking, eating, drinking, and smoking influence the bodily sensations he feels. In a letter of 1832 to ‘Dear Richard’, probably his younger assistant Richard Owen, although he signs the letter ‘Your afficshunnut brother William’, he writes of his hunger and thirst experienced on a long walk on a ‘sweltering’ day near Putney. He recounts being revived ‘at the sign of the “Bull-dog and Snuffers” ’ where he ‘requested the presence of a pint of ale (scotch!) and a small crusty loaf and cheese’. He then recalls the effect that the bread and cheese had had upon him:

In the space of 10 minutes, the peculiar sensations began to diminish […] the weight at my heart became more equalized by the exhibition of aliment to the other non-supported viscus (i.e. my Stummick) and in 7 minutes more my disturbed equilibrium was perfectly restored.

Feeling that this description was not illustrative enough, he writes: ‘I cannot forebear giving you an idea of it in a graphic form, as I think that mode will best explain my feeling… you will now, perhaps, appreciate my state of mind.’ He then sketches out two sets of scales. The first scales are unbalanced: the stomach outweighed by a heart labelled with the words ‘Regret, Anguish, Hope & Fear, Affection, &c &c &c’.[4] The second scales are balanced: the stomach now weighed down with ‘Ale, Bread, Cheese, Cigar &c’, which has offset the ‘Regret &c &c &c’ located in the heart. Broadly: he went for a long hot walk, and felt better after going to the pub. This is an informal and humorous communication about the workings of the body, but one that is grounded in Clift’s medical training: the importance of internal balance, the intertwined nature of body and mind, stomach and heart, and the connection between emotion (located in the heart) and bodily acts of eating, drinking, and smoking.

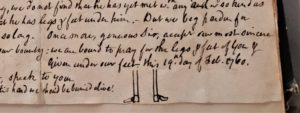

Ink and pencil sketches of body parts appear in eighteenth-century familiar letters for both humorous and more serious illustrative purposes. They replicate familiar faces, they communicate developments in drawing skills, they illuminate descriptions of physical appearance and characteristics, they illustrate feelings and sensations. They serve to create physical and bodily connections between letter-writers separated by distance, connecting writer and recipient in shared sensations: to see what they were not physically present to see, to feel what they were not physically present to feel. More usefully still, they can act as the punctuation that draws a piece of writing to a close, like this pair of feet used as a valediction by the Twining family: ‘We are bound to pray for the legs & feet of you & yours. Given under our feet, this 19th day of Feb. 1760’.[5]

[1] Cumberland Papers, British Library, BL ADD MS 36491, f.82.

[2] Twining Letters, British Library, BL Add MS 39929, f. 32.

[3] Clift Letters, British Library, BL Add MS 39955, f. 197v.

[4] Clift Letters, British Library, BL Clift ADD MS 39955, f.215.

[5] Twining Letters, British Library, BL Add MS 39929, f.2.