by Esther Wilson, University of York

Given Penelope Corfield’s focus, in The Georgians, on connecting with the 21st-century audience, and my own public history background, Tom asked me to emphasise this sort of angle in my comment. I suppose in summary, I really found it a wonderful read and appreciated the way in which the wider public was encouraged to engage with the histories being shared. There is in The Georgians a real blend of clarity and subtlety, big themes and gloriously tiny details and something (hopefully) for every reader to get out of it.

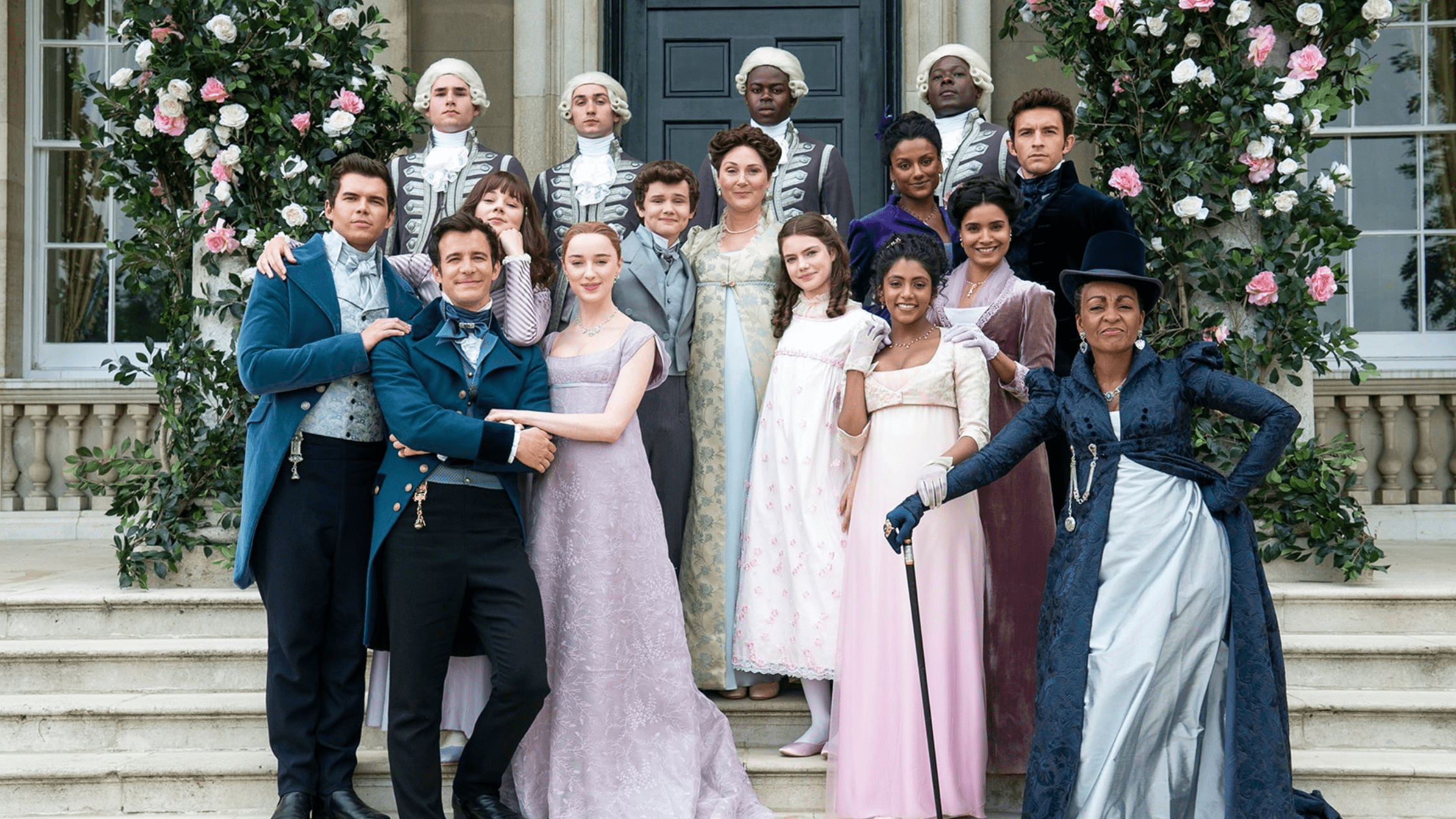

The book has a real emphasis upon the relevance of 18th-century histories beyond mere popular trope and stereotype, but doesn’t give way to cliche. From the outset, reflections about how people 200-300 years ago “thought of themselves” beg the question of what we think of ourselves in the 21stC through the unfolding lens of 18th Century histories. To me, the book complicated what is meant by representing the past. It’s not just about how the 21st century has represented the 18th century in popular heritage and culture (e.g. the preface’s allusion to Bridgerton or Pride and Prejudice). Rather, the it seemed to almost critically flip that perspective – it invoked instead a sense of how our current society and present conceptualisations of national and individual identity mirror (and build upon) those of our forebearers some 200-300 years ago in a way which was careful and not anachronistic. What has the legacy of the 18th century really been and how does this speak to the ways in which we remember and represent it in our practice and daily lives?

Perhaps most important, though, was the accessibility of such thought and the book’s work in general. It felt like a book that many people could glean something of real value. The breadth and specifics of detail were masterfully woven together, covering different strands of public and private 18th-century daily lives between contextual outlines, simply-given fact nuggets and historiographical comment. This approach not only made the work interesting to a broad range of readers who may relate more strongly to some topics and approaches than others, but made accessible some of the difficulties of academic research that perhaps aren’t so obvious to those in different consuming publics who are not engaged in such full-time endeavours.

I particularly liked how these recontextualised surviving/hidden/forgotten ‘things’ that demonstrate some of the interconnections between 18th and 21st-century life. Although I’ll admit that I found some of them a little obscure, I really appreciated how broad the categories were: Hogarth, plays, national-level sites of renown down to local heritage organisations (some of which weren’t so far from where I grew up, which certainly connected me to some of the histories). For me, the time-shift sections not only provided tangible heritage examples for readers to reflect upon, but helped to widen awareness of and encourage reflection upon how we all (a) actually learn about history and (b) think about ourselves across time as part of our day to day lives. These sections really seemed to recognise and encourage everyone’s involvement in conceptualising and promoting certain ideas, conversations and understandings about past and present. Complementing the breadth and depth of the book’s chosen content in general, these sections seemed to cement a sense that such thinking about past, present and identity is very much not down to solely professors or researchers. Rather, it is something that everyone is engaged in every day, whether they’re aware of it or not.