It’s all about the assessment: In 2026 we should have separated formative and summative assessment. In breaking the covalent bond between these two unequal twins we allow each to do it’s proper job, unencumbered by the other.

I recently asked my students why they were not engaging with all the wonderful and innovative formative assessment that I had made available for them; couldn’t they see that doing this material during the course would help them in their learning and make the revision process later on a breeze?

The answer was no: they had a summative assessment in a different module and that was the only objective currently on their radar. So it seems that students view the collection of modules they are doing as a linear track, with the next summative assessment dominating their horizon. The next one in the sequence looms large once the previous has been completed. In this landscape, summative assessment (and it’s role as feedback) takes a back seat. Students see it as a luxury rather than a necessity. We try to mitigate by providing skills matrices as road maps that indicate where feedback inform subsequent assessments, but these seem to fall through the cracks between the modules.

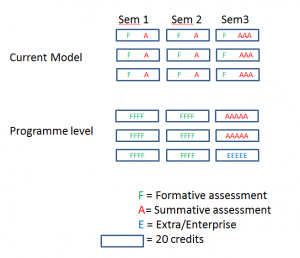

So how do we dissect apart assessment and feedback? In the current model we have individual 20 credit modules containing some formative feedback, a little in course assessment and a final examination period in semester 3 (see figure below). Students see the sequence of summative assessment at the programme level but ignore the important formative tasks. While we might provide a little formative feedback in semester 3 this is largely revision, focusing on the upcoming exam and merely reinforces the exam driven culture they have had since A level.

Truly programme level assessment could be one solution. In this scenario we could deliver 120 credits in semester 1 and 2 unencumbered by the distraction of summative assessments. Instead a series of formative assessments could be provided to enable deeper learning of the material; these could be simple required elements to give a small carrot to encourage completion. The semester three examination periods could be used to assess all credits. But instead of a one-to-one link between module and exam we should reduce the number of exams and increase cross topic synoptic questions, testing more accurately for critical analysis and synthesis skills.

In the programme level model we would significantly reduce the amount of summative assessment. Since we would be assessing all the learning outcomes of the modules in one single period, examinations need not be dominated by essay writing under controlled conditions but could include practical tests, presentations, group work, posters, dissertations , mini projects videos etc. Depending how and when assessment was scheduled, time could be freed up to deliver more material that sits outside the conventional programme, such as placements, volunteering and enterprise modules.

The above is a one year semester plan, but we could be more radical, shifting formative assessment to the end of the second year, or even just the final year. This would create a number of issue to be addressed, including progression and students being out of the summative assessment environment for a long period. But if teaching and learning are underpinned by fit-for-purpose formative assessment, summative assessments blocks at the end of year (or end of degree!) need not be a shock. We should free formative assessment and it’s feedback from the shackles of summative exams!

Hear hear!

(The last paragraph contains one “formative assessment” that should be “summative assessment”, but the message is clear and correct, in my analysis).

The benefits of formative assessment (over summative) include:

+ less need to use cumbersome, centrally-administered computer systems that are not fit for purpose

+ reduction in student stress, resulting in more opportunity for deep learning, fewer visits to the mental health team, and reduced need to access Welfare

+ reduction in staff stress, for the two reasons given above, and also because writing fair exams, and marking them fairly is stressful and time-consuming

+ a change in the students’ perception of where and how learning occurs. Hint: it does not occur from playing “mark token bingo”; it occurs by hours spent in the new library, and going for long walks, and occasionally but not too often writing something down when it has begun to sink in.

There are very few downsides (I can’t think of any). As long as students get formative guidance, they are happy students in my experience. Formative guidance can be written ahead of time, and students can mark each others’ work, and/or compare with a prepared ideal example released soon after a formative task is given.

best regards

Joshua Knowles

Professor of Natural Computation, School of Computer Science

Certainly the semester scheme with summative assessment at the end of each is generally a poor idea, which is why many do not use this any more after a brief experience many years ago; semesters are purely nominal in Physics and Astronomy. It would be good to separate formative from summative reviews for some project work, e.g. giving detailed feedback on draft submissions and then pro forma feedback on a revised submission for credit, but that requires a uniform level of engagement from all staff involved, which is not always easy to achieve, and raises the potential for significant unfairness.

Moving summative assessment to a single period per year seems better for those not already doing so, as convincingly argued by others. However, the ‘elephant in the room’ is the lack of available space for exam venues on campus. If we force even more exams to take place in the summer term, perhaps a more devolved approach to exams could be considered, allowing individual Schools more control over how and when they assess their own taught content, in contrast to the current highly centralised exams system, which seems a single point of failure and considerably understaffed.

This is a joint entry from Julia lodge and Ron mechan.

In nursing the clinical component is aeeassed by a “patchwork”. The students study three modules that have a practice component. At the end of the year they will have demonstrated overall competence for particular clinical skills in each module. These are gathered together into a Practice portfolio. These are are assessed (pass /Fail) by the practitioners that they are working with. In the future all of theses competencies will be brought together into one 30 credit module. Effectively this reduces the assessment burden on the student and aknowleges the effort they have made. It is also synoptic bringing all of the clinical aspects together. One of the consequences is that a student who passes will get 100 % for the module. Sadly this module will not count to the degree classification.

We would be really interested to know what students on other courses think about this model.

I certainly agree that students, especially in the final year, are overwhelmingly preoccupied by their summative assessments. To a certain extent, this makes sense because this is the stuff that counts (in their eyes). We see lots of students who will disengage from the material discussed in the seminars because they are not intending to write on that particular topic. We can be creative in designing assessments that require them to draw on material studied throughout the module but this only gets you so far. What I would like to see is the summative assessment emerging more clearly from the formative work with feed forward replacing feed back and more use of so-called ‘iterative’ feedback. I’d probably abolish most end-of-years exams altogether and replace them with other assessments – projects, blogs, reports, presentations, traditional essays etc. For me, this would have to go hand in hand with plans to revamp the shape of the University year. Our current academic year with its space for a formal exam period really makes the choice of an end-of-year exam as the logical choice for many modules.

It is possible to separate summative assessment from the teaching and formative work that goes on in modules…Brunel Uni do this in several programmes and there are summative synoptic assessments that cut across the taught modules in each year of the programme. Overall the assessment load is reduced and there is a major emphasis on assessment for learning. However, this assessment strategy does make it more difficult to give students choice across programmes and would be challenging to build into a truly semesterised programme with exams twice a year….

Interesting discussion…We tried to establish a ‘Firewall’ between summative (20%) and Formative (80%) assessment, primarily by having the person directly working with students ( a Tutor in the PBL framework) having no Summative roles. I did a small study comparing attitudes of medical students in a more conventional curriculum and in ours. It was presented in a meeting, but not published, but would be glad to share a powerpoint on request.