On looking back at the scholarship project I have just completed, I feel a sense of relief. This is certainly not because it has come to an end – I am extremely sorry that the project is over, and I’m still eager to continue researching the topic, and helping my scholarship lead, Tara Hamling, if required. The relief stems from my knowledge that hopefully I have contributed to the long overdue task of finding, collating and organising records of early English wall paintings, when the future of this kind of Tudor and Stuart vernacular art is worryingly uncertain.

In response to the recommendations given by the 2014 Symposium on wall paintings to tackle this information deficit surrounding interior decoration in lesser houses, we had two central goals for summer 2017. Firstly, to create a database in which all the more obscure examples of wall paintings sourced from antiquarian literature, such as surveys made by Philip Mainwaring Johnston and Francis Reader in the 1930s, could be stored. The second objective was to conduct my own research by parish in the online Red Box Collection to find a minimum of two potentially new and as yet unstudied murals. With eighty entries, and corresponding photographs, in the database so far, and an outcome of three new wall paintings from looking through cards for the counties of Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Berkshire, Kent and Bedfordshire, I am proud of the beginnings Tara and I have made to the cataloguing of this wide but unappreciated history of the decorative arts. Of course, there is still plenty more to be found, and inputted into the database, given the abundance of this art form in early English ‘middling’ communities.

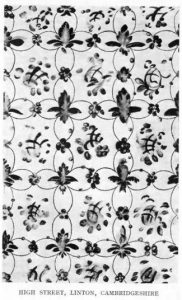

Aside from this statistical evidence of my time researching, I have noticed several points of personal growth and enlightenment. In my previous experience in the history of art I worked within a significantly different timeframe and artistic style, so while I was familiar with the study of art via iconography and aesthetic classification, training in nineteenth-century fine art could in no way prepare me for what I was to encounter. In truth I had no idea that you could expect to find the interior wall surfaces of sixteenth and seventeenth-century buildings totally covered in geometrical, foliate, figural, landscape or heraldic schemes – all of this has certainly been a revelation to me. I found it fascinating to investigate how occupants commonly endeavoured to enhance their domestic space by imitating wooden balusters, panelling and other architectural features using the tempera paints they applied to their walls. It has been a new world of patterns and biblical inscriptions that I have had the pleasure of exploring. For instance, discovering the geometric design with acanthus foliage and pineapples in the High Street, Linton one day, and, a depiction of the Journey of the Magi to Bethlehem in a Hampshire farmhouse, the next, offers a snippet of the variety of wall paintings I documented. Alongside learning about this visual aspect of early-modern everyday life, I have had the opportunity to broaden my archival research and cross-referencing skills to build a final product that could be utilised by other academics.

I am grateful to the Undergraduate Scholarship scheme for the opportunity to participate in the preservation of the memory of early English wall paintings for future generations, and for Tara’s valuable guidance in this topic area. I have to say I am rather envious of prospective scholars who can look forward to starting up their projects, because I wouldn’t hesitate to do mine all over again.

Ellen Smith, BA History