I was thrilled to undertake a PGT Research Placement with Dr. Kate Smith working on her project, provisionally entitled Absent Objects: Lost Property and the Making of a Modern Metropolis, 1695‐1914, which considers how ideas of lost property develop, and how mechanisms of how people found and recovered their lost (or stolen) property change over time.

I had worked on this project as an undergraduate, collating information from lost (or found!) property advertisements placed in The Times (though an earlier project had looked at other newspapers). This time I was using this data to create a visual representation of the locations of intermediaries (the people who had lost items, or who would receive them and give a reward) – in other words, to create a map of people and places involved in the ‘trade’ of lost and found items.

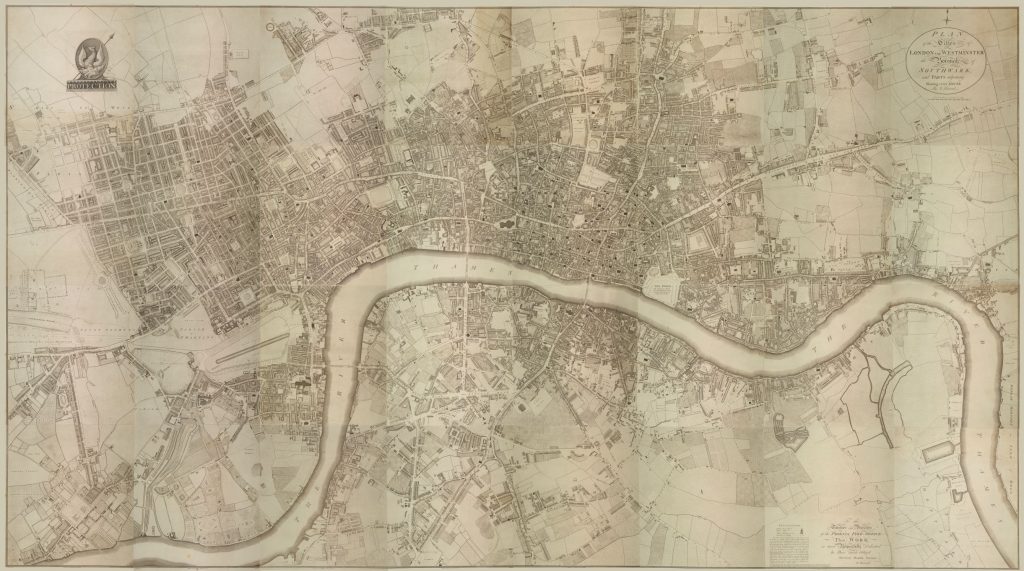

Since I had already undertaken some work on the project in the past, I was familiar with it, and with the database. However, the project was daunting in scope. I had to sort through nearly 700 advertisements, remove duplicates, find their address, and then to determine an exact location for each one. Next, I was to mark each location on a copy of Richard Horwood’s map of London (devised between 1791‐1799). Finally, once 1710 was complete, I was to repeat this with the data for 1720.

This should identify who the intermediaries were. Identify any names or locations which appeared time and again, and identify any ‘clusters’ either of geographical areas where there were many items which had been found. Additionally, it should show common professions or types of business which were used to help restore unite people and property.

My initial focus was therefore two-fold; on cleaning and formatting the data (including removing duplicate advertisements) and in locating the intermediaries; and on learning how to use mapping software. One thing I was not so familiar with was using mapping technology, in this case a potent tool named Geographical Information Systems (GIS), so I realised that there was a great deal for me to learn. In preparation for the project I spoke with a colleague, a PhD candidate specialising in battlefield archaeology who makes extensive use of GIS, in order to understand its potential and limitations. I also undertook some tutorials and familiarised myself with the range of help and advice which could be found on the MapGIS forums.

The 1710 database was sorted and cleaned up, and locations of the named primary intermediaries were determined. It was a fascinating investigation to discover where the intermediaries were, and to learn how addresses had changed. Rather than giving a street number most directions were to (or near to) a landmark, often a business, many of which no longer existed – and in several cases roads had vanished or been renamed (some, several times!).

This meant that locating some of the intermediaries was a puzzle worthy of Sherlock Holmes. Some buildings or businesses still exist, and others have left a significant historical footprint, so whilst some were located using a combination of detective work, brain power, estimation, and looking at patterns in tea-leaves, others I was able to locate with remarkable accuracy.

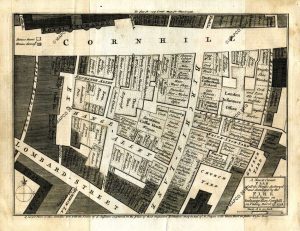

A good example of a ‘cluster’ of intermediaries was the assorted coffee- and chocolate-houses located near the Royal Exchange in Cornhill. Not only do some exist still, but they have left a significant presence in the historical record, which has inspired other historians to do some of my work for me, and a very handy insurance map of where each was after many buildings were destroyed by fire in 1748.

Unfortunately, I ran out of time and I was not able to complete as much of the project as I would have liked; whilst the dataset for 1710 is complete I was not able to turn the data into a map. It was disappointing not to achieve the output that I wanted to, but I am proud of the work I did and hope that it will prove useful. For myself it was an opportunity to work in a different way, in a different period and a very different area than my own research. Therefore, the different way of approaching research, and understanding some of the challenges involved in constructing useful maps, is something I am very glad to have experience of.

Overall, this has been an enormously positive and rewarding experience, and being able to revisit a project which I had done some work on previously allowed me to understand something of how an academic research project develops over time, something which has encouraged my desire to continue further study once my Master’s degree is complete.

Rik Sowden, MRes Early Modern History

Read about Rik’s experiences of finishing his UG Research Scholarship, and how it led him to Postgraduate study, here.