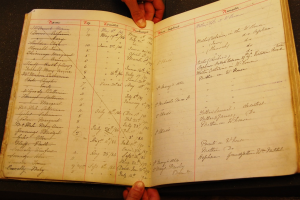

My role in the project ‘Public welfare, private charity: the archives of the Sisters of Mercy, Handsworth’ was entirely straightforward: I was to read the entry register book of the St Joseph’s Home for orphaned Catholic girls, run by nuns and established in 1884, and transcribe it onto a spreadsheet. I was, admittedly, somewhat dismayed to find that I was destined to spend the next five weeks of my life doing what was essentially data entry. Despite my supervisor’s promises that I would find the document more interesting than it looked, the St Joseph’s Home entry register appeared to be little more than a list of names, dates, and perplexing Victorian acronyms.

What I learned, however, was that you could discern a lot more information from a single administrative document than I had ever imagined. Whilst there was no escaping the fact that trying to decipher incomprehensibly elaborate Victorian handwriting and copy thousands of names and numbers was incredibly time-consuming (and a great strain on the eyes and wrists), the St Joseph’s register slowly revealed its secrets – tragic accounts of children born into the grimy world of industrial-revolution era Birmingham, abandoned by their parents, expelled from workhouses, orphaned during one of the many outbreaks of disease.

The book spanned from the 1884 until the late 1930s, and with a little detective work, I was able to track some of the major social developments of the period through the sparse information recorded in the ‘additional remarks’ column. Accounts of children detained at St Joseph’s under the Poor Law Act increased after 1906, following the Liberal Welfare reforms. In 1911, there are records of a pair of sisters sent to Canada under the now-controversial child migration scheme. Mentions of the NSPCC appear after its foundation in the late 1880s. By 1915, there are even records of children orphaned after their fathers’ deaths in first world war.

Whilst, more than anything, the thing that kept me coming back to the archives each day was my inexplicable fascination with lives and affairs of these long-dead children, I also quickly became aware of the academic benefit of my endeavour. Understanding the antiquated and illegible script became increasingly easy as I continued my task, and the resident archivist spent a great deal of time showing me correct archival practices and how to handle the original document correctly. I also found it quite gratifying that I was creating something that had an actual, real-world use: my ‘finding-aid’ was not only for use within an academic context, but would also be made available to both the current Sisters of Mercy and family historians conducting genealogical research.

Despite the somewhat monotonous element of the role, there is no doubt that my experience was a positive one. I believe the skills that I have developed during the process will prove invaluable during my third year and any further study that I undertake, and I am very grateful for the opportunity to gain an insight into professional archiving. I would highly recommend the UGRS to any history undergraduate.

Eleanor Hammond (BA History)