by Lucy Cutter

The Ladies of London project focussed on Angelica Schuyler, an American socialite who resided in London between 1784 and 1797. During this time Angelica was a member of British high society, her circle including, but not limited to, politician Charles James Fox, artist Maria Cosway and the Prince of Wales. Over the course of this project I explored what it meant to be a ‘good woman’ in the 1780s and 90s, which helped to bring an individual like Angelica to life.

Shoba Narayan, Ta’Rea Campbell (Angelica Schuyler Church), and Nyla Sostre in the second National Tour of Hamilton. Photo by Joan Marcus.

“The government of the house is generally left to the wife, by the husband, who readily submits to her administration.” – Abigail Adams

Women were responsible for household management, including the hiring and supervision of servants. Conduct warned women to be wary of their servants, whom in general were believed to be untrustworthy, ignorant and cunning. The only effective way to manage a household was keeping a calm temper and approaching one’s servants with caution. Women are warned to set an example to their servants as they would their children. Instructed to act uniformly, never finding fault without just cause, avoiding habits such as cursing and keeping their servants out of bad company “lest they learn the pollutions that are in the world.” When employing servants there were other things an elite woman may consider in the 1780s and 90s as it became increasingly fashionable for households to have black or Asian slaves as a symbol of wealth and status. Another fashion was having French valets, Ladies maids or, most of all, French cooks which had long been a sign of sophistication in London’s elite households and restaurants.

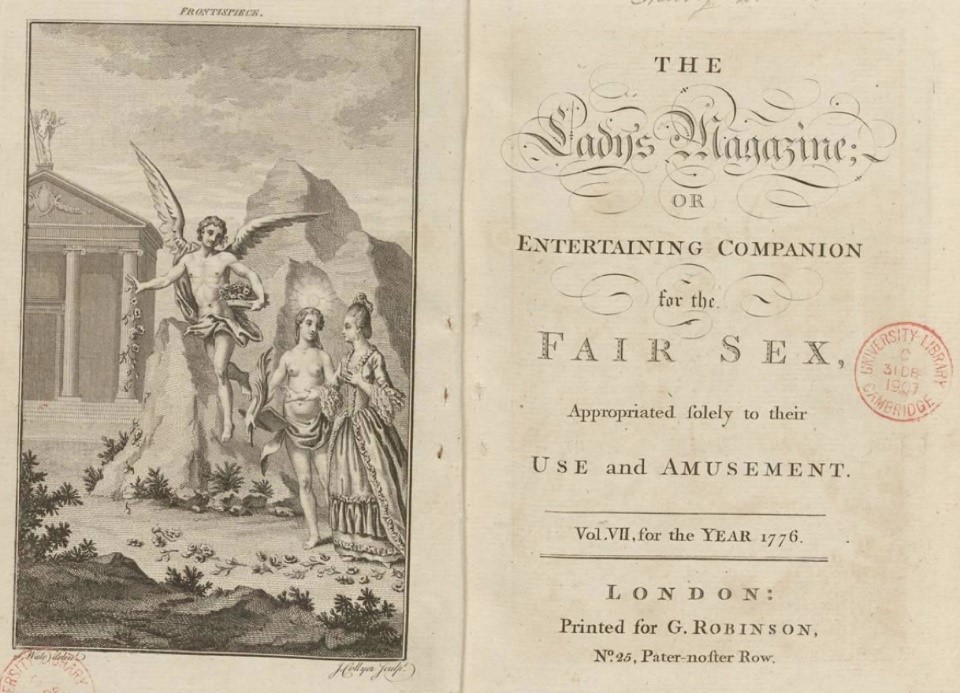

Figure 1, Lewis Vaslet, The Spoiled Child, 1802

Nonetheless, to rely wholly on one’s servants was heavily criticised in contemporary print culture. Women who did so were branded as idle, useless and opulent, prioritising a social life in company over their domestic life. Young bachelors were also wary of young women who were too concerned with appearance as they believed these women would deem domestic affairs unworthy and deplete her husband’s funds. Women were instead advised to dress with a modest neatness when searching for a husband as this was more likely to convey elegance and save a young woman from the judgement and envy of her peers. This presents a double standard that modern women may find somewhat familiar. The appearance of women was criticised heavily in print culture, often in a contradicting manner. The Lady’s magazines and other popular literature would criticise women who were too engaged with their appearance while the following chapter of the same periodical would praise the dresses seen at the Queen’s ball. Comparable to modern day commentary of the fashion adorned by celebrities at red carpet events.

Figure 2, The Lady’s Magazine, 1776. The Lady’s magazine produced yearly volumes that compiled the biweekly periodicals released throughout the year. The Lady’s magazine was immensely popular among high society women, discussing fashion, marriage, and other topics that were considered relevant to women. The magazine advised women how to behave and how to be a ‘good woman’.

A good woman in the 1780s and 90s was also expected to be educated to some degree. Women were encouraged to have a knowledge of politics, however only of domestic affairs. This rule did not work for Angelica. Angelica was considerably ahead of her time as through her correspondence, and her residence in numerous countries both sides of the Atlantic, Angelica formed and maintained connections with a number of male American and French revolutionaries. This included Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and the Marquis de Lafayette. While women were expected to be educated, the general scope of this was to be fairly restricted and limited. Skills that a woman needed was restricted to keeping basic accounts, cookery, needlework, music, French, geography, drawing, dancing and writing letters. Other subjects would be deemed out of a woman’s realm and an overly educated woman had potential to neglect her domestic duties. While in the modern western world women pursue higher education and obtain careers in high paying, influential sectors, the media still holds some of the dated views of Angelica’s time. Women who put their career ahead of children and the household can be criticised for trying to ‘have it all’.

Studying the social and domestic lives of women in the 1780s and 90s revealed that Angelica was a very colourful woman who did not always follow the rules laid out by print culture. This research also revealed some interesting similarities between the lives of women in the 1780s and 90s and of women in the modern day. While law no longer restricts the rights of women in the ways it did in this period, women still face a lot of the same criticisms and are still advised how to behave and be a ‘good women’ both in print culture and new media. There are obvious differences and progresses made for women in modern day, but these continuities help us to understand the social and domestic lives of women in the 1780s and 90s in the context of the modern world.