My name is Jess and I have just finished my first year studying BA English with Shakespeare Studies. As a collaborative research intern, I have been keen to explore how recent productions of Shakespeare plays have made the texts relevant and interesting to modern audiences, working on a project called ‘design, contemporaneity and relevance on the Shakespearean stage.’

A question that I think a lot of us ask ourselves and others is: how is it that a playwright who died over 400 years ago continues to be the most popular in the world? Many talented playwrights have existed since, yet it is Shakespeare’s plays that dominate the modern stage, continuing to draw in both theatre companies and audiences. My main intention as a CRI was to learn more about how and why this happens.

In my research, I chose to focus on productions of Hamlet. Partly, I chose Hamlet because it is one of Shakespeare’s most well-known plays. However, I also felt drawn to the play by its absence of many female characters. The play only has two women: Gertrude (Hamlet’s mother) and Ophelia (Hamlet’s lover). In an atmosphere dominated by men, Gertrude and Ophelia are often overlooked and undermined in their capacity to think and feel independently. I was interested to see how modern productions of the play might engage with this female portrayal, ultimately with the hope to understand more about how potentially outdated representations (in this instance of woman) exist when performed to more socially conscious audiences.

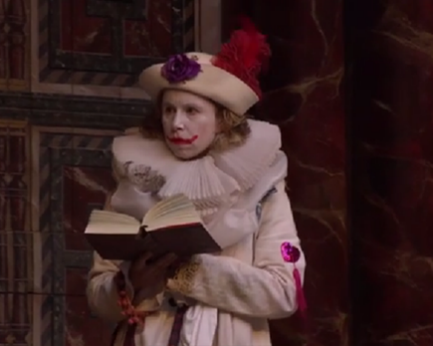

I started by watching the National Theatre’s 2010 Hamlet, directed by Nicholas Hytner and later watched the Globe’s 2018 Hamlet, directed by Federay Holmes and Elle While. Both productions reconsidered the ways in which Gertrude and Ophelia have traditionally been portrayed. In Hytner’s production, Gertrude is conniving and deliberately deceptive to protect her status as Queen, emphasised by the unique interpretation of the closet scene. She sheds an image of weakness that Hamlet seems to have thrust upon her, instead assuming a more compelling, three-dimensional personality. Meanwhile, Ophelia’s death no longer represents a tragic act of desperation, but instead becomes a ruthless murder that Gertrude helps cover up.

What I found most interesting about this production, however, is that although these choices seem totally subversive of what we traditionally understand to happen in the play, the choices were made with the original text at the heart of it. I had the opportunity to visit the National Theatre Archives in London, where I gained access to press releases, workshop videos, exclusive interviews, programme information, and more. Through this, I discovered that each scene was rehearsed multiple ways, playing out several interpretations, with the final product being that which they felt most honest to the original script. I have, therefore, unexpectedly realised that making Shakespeare relevant doesn’t necessarily look like changing the story, but instead can be found in being more open-minded to the array of possibilities for interpretation. The plays are already so complex, and as a result new meanings can be found upon every read.

This internship has subsequently opened my eyes to the complexity of relevance. We can find relevance in just about anything. Relevance doesn’t have to just look like replicating modern ideals, it could be quite the opposite- we find interest in our own views or assumptions about a play being challenged. Where there is possibility for new perspectives, there is relevance. This bodes well for the future of Shakespeare on stage, and I have thoroughly enjoyed getting to explore a topic that I am so passionate about more closely.

Jessica Towers, BA English with Shakespeare Studies