My name’s Theo, I’m a second year Classical Literature and Civilisation student, and I had the opportunity to intern in the ‘John Crowfoot and the Gerasa Archive’ CIR project under Dr. Daniel Reynolds, in collaboration with the Palestine Exploration Fund. My role, along with my co-intern, was to digitise the archaeological records of Crowfoot in his exploration of early Christian churches in Gerasa, Jordan. This ticked a variety of interests I have – not least wanting to do museum and archive work in the future – so I knew I had to apply and was over the moon upon getting the internship.

My expectations of this internship were coloured by previous volunteer work I did in an archive before university, that I soon discovered was inaccurate and, quite frankly, selling my internship short. In this volunteer work, I assessed archaeological reports and fed simple information – names, number of artefacts, specific place – to the archivist, who put the data into a spreadsheet.

Given I was now to be an intern – certainly a step up from a simple volunteer – I assumed I would be promoted to putting the data into the spreadsheet myself. Other than that, I would similarly be finding readily-presented information on well-labelled and catalogued forms and transcribing them onto a computer, having been given a guide that I’d conform to lest I entirely contradict the catalogue style of the archive. Through this, I could familiarise myself with an archive environment and workspace, be introduced to cataloguing systems by working alongside one, and learn more about early churches through exposure to primary archaeological resources – an overall win in my book.

The only detail I correctly predicted was that I would be inputting the data personally.

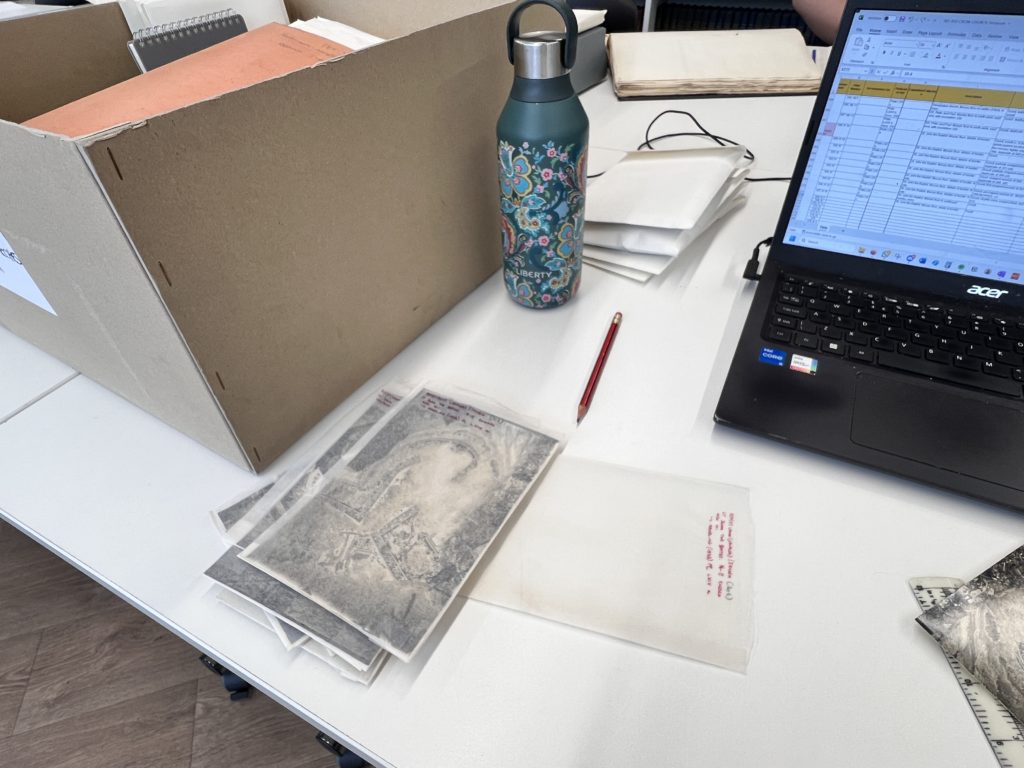

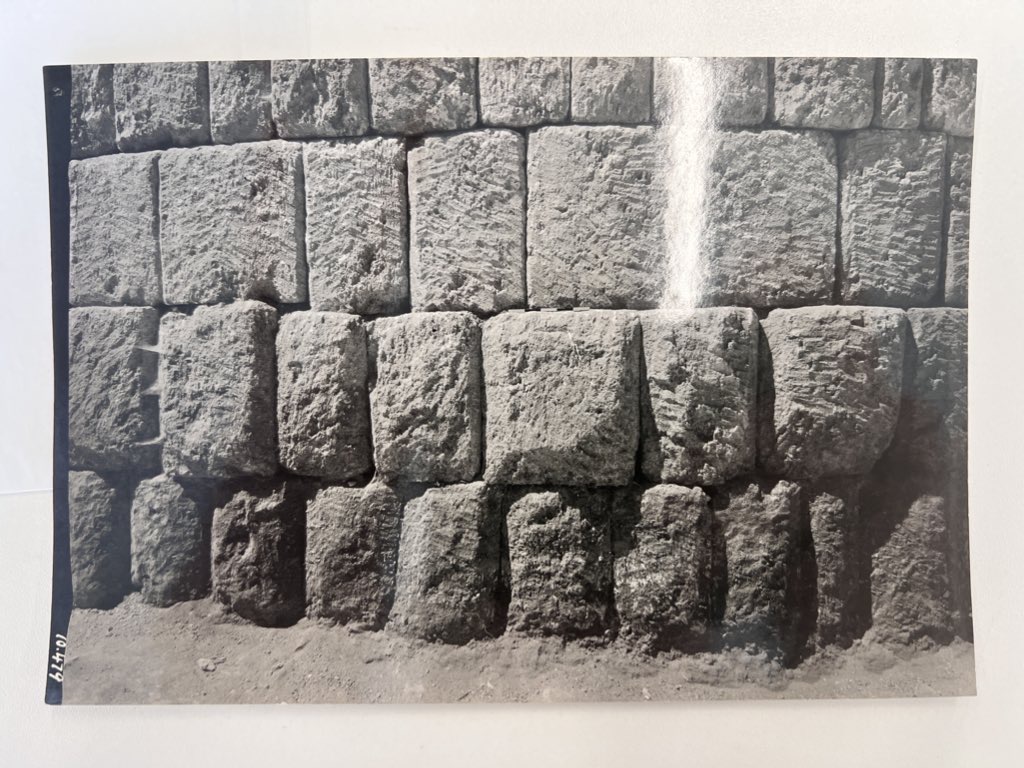

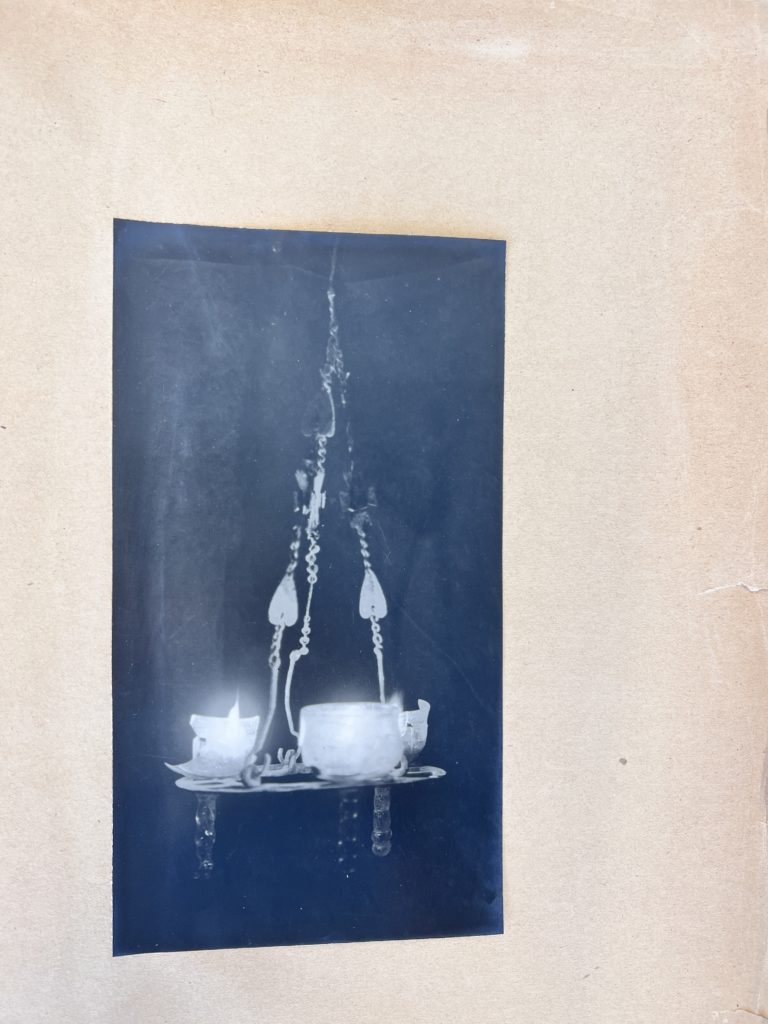

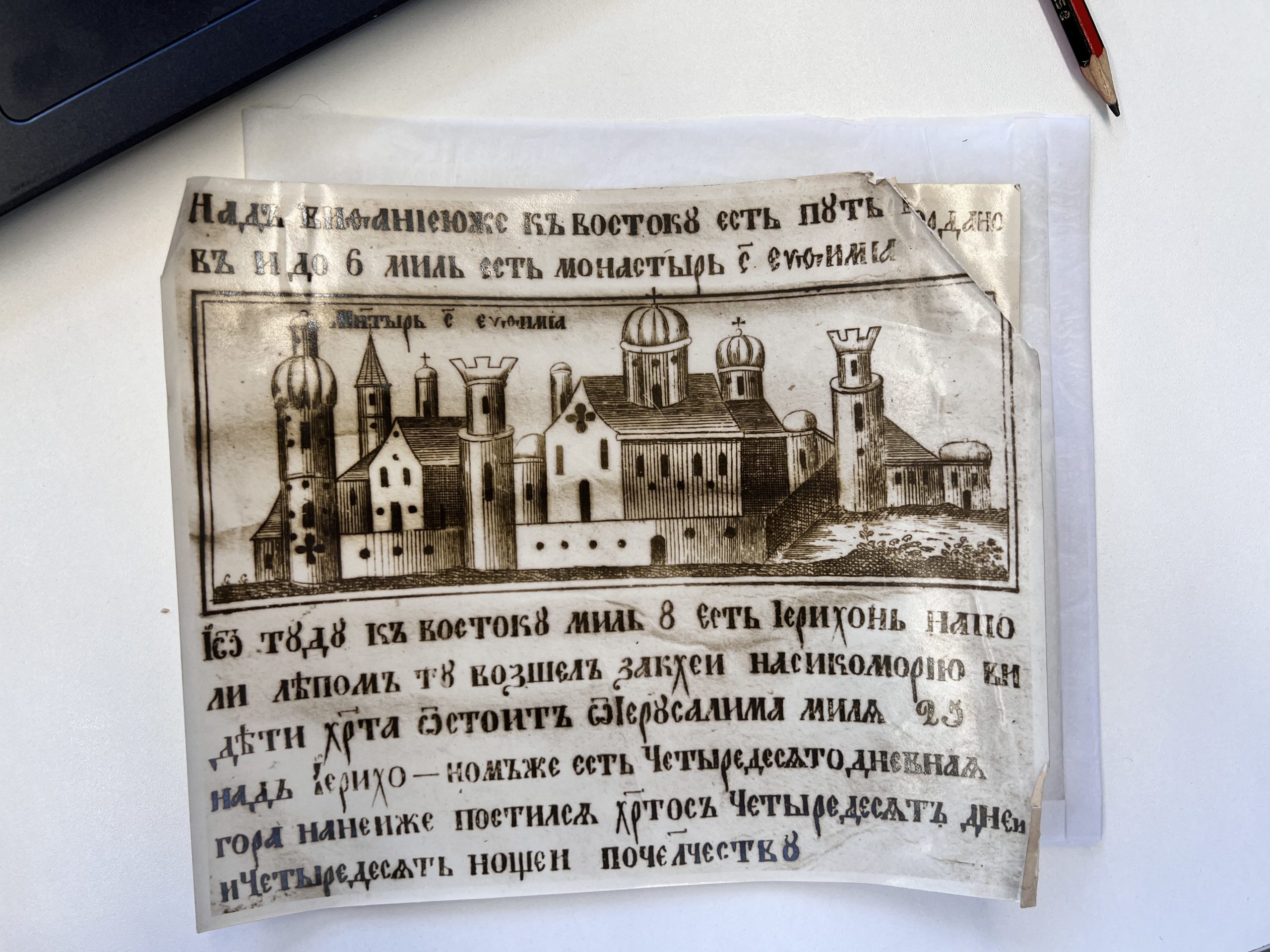

First, instead of archaeological reports and forms, I was presented with a series of letters, notes, and photographs – this was not the readily-presented information I had expected. My box of records held the personal, pre-publishing notes and thoughts of a nearly-century old excavation, with no pre-existing catalogue or guide for me to consult. This meant I had to apply an amount of frantic searching and Professional Where’s Wally to come up with details to catalogue – a mean feat when given generic pictures of random walls.

Whilst my box of records had been given a cursory overview and attempt at organisation, none of the 3 previous attempts had actually finished this. So, a not-small part of my cataloguing process, after working out which obscure bit of wall had been photographed, was determining why it had been filed with photos taken at the other end of the site. Some pictures weren’t even of my site. This meant I had to actively research the area, consulting the published reports and cross-referencing various publications, giving me a far more in-depth understanding of the area and the excavation work done.

Given this lack of prior organisation, I was not only allowed to have my own thoughts and methods in cataloguing and digitising these records – I was expected to. I was taught effective cataloguing through working it out myself, along with guidance as needed, of course. Not only have I thoroughly enjoyed this work (and how satisfying it is), but I am also now a world leading expert in Where’s Wally.