We are a team of four individuals from a variety of courses (English Literature, History, History and Politics, and Classical Literature and Civilisations) who were picked to work as interns in Collaborative Research Internship for Dr Imogen Peck on her most recent project. This involved cataloguing the contents of a set of family archive books about the prestigious Cowper family and partaking in a conference on the wider topic of family archives.

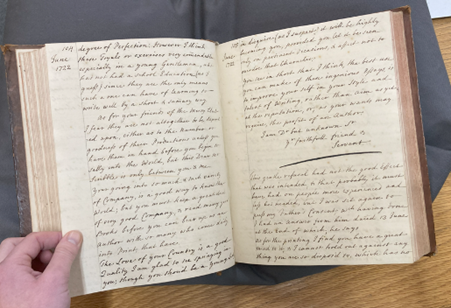

Sarah Cowper was the daughter of William, 1st Earl Cowper and Mary Clavering, Countess Cowper, and the granddaughter of diarist Dame Sarah Cowper. We know relatively little about ‘our’ Sarah’s life. She died unmarried and childless, and her ‘family books’ appear to be the most significant thing left behind after her death. Comprising of 8 volumes and spanning the years 1692 to 1737, these books are a chronological compilation of letters, diaries, and assorted other writings penned or preserved by her family. Sarah inherited these family papers after the death of both her parents in the winter of 1723/4, but we aren’t entirely sure when Sarah produced the books. Based on the way some people are referred to, and which dates are included, we believe she started her project sometime in the 1740s.

The third book in the collection spans the tumultuous years 1714 to 1716 with letters, diary entries and political speeches filling the volume’s pages. While working through the book, Lady Mary Cowper’s influence over the circles within the court and the political landscape was striking. Alongside her close relationships with influential figures, Mary’s fluency in French placed her in a position of power as she translated messages and treatises from her husband to the King. The process of organising, transcribing and formatting her family papers was one that Sarah perhaps felt a duty to undertake after inheriting years of national and family history, yet while working through the volume we came to understand the sheer investment involved in Sarah’s project, and the time it would have taken to preserve these periods in her family history.

Book five spans from 1718 to 1720 and mostly consists of letters written to Lord and Lady Cowper by various members of the aristocracy, as well as drafts of their letters. Many of the letters in the book’s first part highlight the nobility’s response to Lord Cowper’s resignation of the Royal Seal and his position as Lord High Chancellor. Also, many letters comment on the estrangement between the Prince of Wales and King George I, and how Lord and Lady Cowper tried to reconcile them due to the quarrel negatively affecting English politics in a time of crisis. As well as including letters of political significance, Sarah Cowper includes letters about significant family events, such as when her family was ill with scarlet fever.

Book six spans the years 1721-1729. It consists mostly of letters from William to Mary prior to their deaths, along with some political acts and events. Throughout this volume, Sarah’s own comments increase as she would have been old enough to remember what she was doing at the time. Furthermore, when she writes about her parent’s period of illness and their deaths, entire pages are taken up by her personal account of the events. Partially because of this, the books generally increase in length, this may also be because she became more passionate about the project or had a clearer idea of how to best tell the narrative.

Overall it was fascinating to work with these manuscript materials, as we had very little knowledge of the time period beforehand, and now feel like we have concluded our research project with a fascinating knowledge base through the lens of a woman in the 1700s. It was especially interesting to acquire this knowledge literally from her own hand, as we read pages of family history while deciphering eighteenth-century handwriting. It felt especially surreal knowing we were highlighting a woman’s voice who slipped through the cracks of history.

Dion Reid (Classical Literature + Civilisations), Charlotte Bell (English Literature), Abigail Wilkinson (English Literature + History), Victoria Barnard (History + Politics)