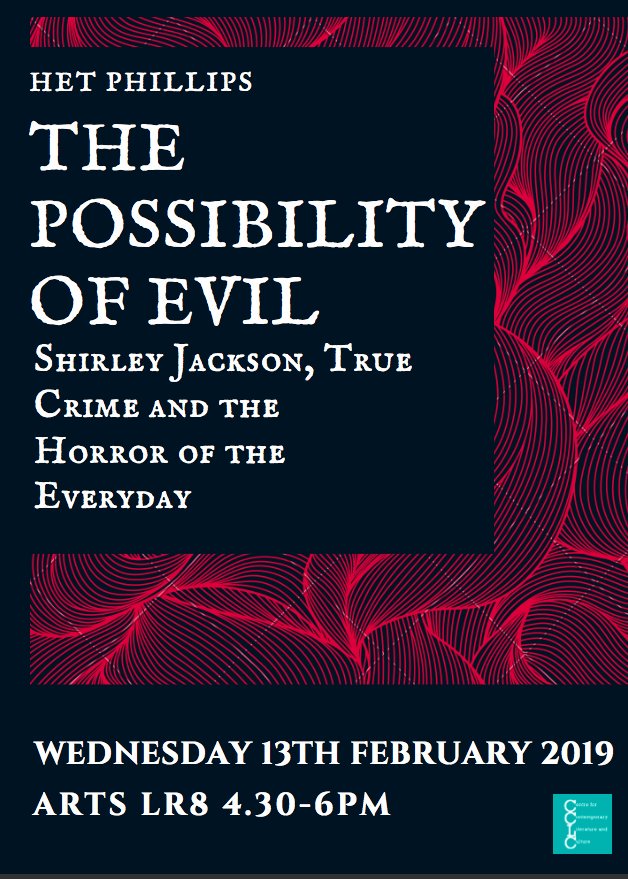

The Centre for Contemporary Literature and Culture was delighted to welcome Het Phillips to speak on true crime and its influence on the fiction of horror and mystery writer Shirley Jackson.

Phillips traced through Jackson’s fiction a fascination with true crime, which brought her repeatedly back to the thematic influences of several real-life cases. In her 1951 novel Hangsaman, as well as the short stories ‘The Missing Girl’ and ‘Louisa Please Come Home’, Jackson returned again and again to the disappearance of Paula Weldon – a student at Vermont’s prestigious Bennington College where Jackson’s husband was an instructor. Details of the case manifested in Jackson’s work – such as the significance of red clothing, the colour of Welden’s own sweater – alongside the themes of threat and escape that Jackson felt characterised the mystery, and which scripted her manipulation of tension in her own work.

Elsewhere, Phillips found traces of the infamous mystery of the Brides in the Bath where George Joseph Smith murdered three of his wives for their money. This real-life incident influenced both ‘The Honeymoon of Mrs Smith’ and well as ‘The Mystery of the Murdered Bride’, stories in which Jackson explored the patterning of shocking recognition, seduction, and deception. Another significant case was that of Lizzie Bordon, who has long been suspected of murdering both of her parents with an axe. The details and themes of the case were found by Phillips to have bearing on Jackson’s own novel We Have Always Lived in the Castle. They also ran through the work of many of Jackson’s successors, including Sarah Schmidt who drew much on the Lizzie Borden case for her 2017 novel See What I Have Done.

Phillips demonstrated how Jackson often used her fiction to produce alternative versions of the same cases in order to explore the many possible outcomes suggested by real-life mysteries. For her, Phillips argued, it was less about solving the mystery itself but about the fact that one can never really know the truth. In fact, even for crimes that appear to be closed, Jackson often works to unsolve them so as to allow for a new direction in which the mystery might go. Some of the brilliance of Jackson’s fiction is in how it can take elements from real-life cases to demonstrate the multiple possibilities they afford our storytelling, and to construct a sense of horror and danger within the ordinary and everyday.

One interesting angle explored by Phillips relates to how Jackson’s own interests in true crime filters into her texts and creates characters who mirror her fascination with mystery. One effect of this, Phillips proposed, was that the predilections of her characters allow Jackson to put pressure on what interests are expected of women, whose integrity is often compromised by their own fascination with true crime.

In the following Q&A session, Phillips further linked this to true crime readership and its relation to gendered expectations, and opened up some interesting questions about what underpins true crime as a genre. She noted how women who were reading true crime magazines often preferred a style of writing that employed male-orientated phrasing. This allowed for a sense of the genre as being something not meant for them and, instead, a taboo that is stumbled upon accidentally. This style of titillation seems perhaps essential to how the true crime genre operates as Phillips proposed that, for each generation, there is always an illusion of revelation or discovery of the forbidden that structures people’s relationship to the genre and lends itself comparisons to pornographic material.

True crime as a genre organised much of the question and answer discussion and gave us a lot to think about. Phillips recognised how true crime is often considered a vulgar and lowbrow form of popular culture produced through the imagined sense of secrecy constructed by each new generation that consumes it. She cleverly expanded on the irony behind its popular image, held even by some who are themselves fans, that having too much interest in true crime is just a bit ‘weird’, even as true crime is consistently the top-rated genre in media such as podcasting. Fascination with true crime is far more common and everyday, and much less bizarre, that the genre makes itself out to be.

Another engaging moment came from a final discussion about the ethics of true crime. In a time where there appears to be a proliferation of commercialisation and sensationalism surrounding true crime, such as in the market popularity of Ted Bundy-related media on streaming services like Netflix, how do we make sure we are not complicit in exploitation and are, instead, able to unpick the problematic in what we enjoy.

Phillips expressed her ambivalence over this point. She concurred that there can be a case made for all of true crime being exploitative. Nevertheless, she finds that a lot of great art has come out of paying attention to true crime and appropriating some of its themes and tropes.

She also recognised an important role being played (in Jackson’s work especially) by true crime’s framing of historical contexts in which authority and morality come into question. True crime can undermine our assumptions, firstly, that the police and authorities always work towards justice and, secondly, that evil can be a neatly cordoned off category able to explain the actions of certain individuals.

These assumptions ignore social influences, which can be better examined by work that engages with true crime. She recognised, finally, that in general there is a lack of tools or narratives necessary for assessing the forces working in society and producing crime. There is too much tendency to reduce each case to a damaged individual whereby whatever produces this damage is left unregistered.

DISCLAIMER: The report on the talk ‘The Possibility of Evil’ in this blog post expresses an account in my own words and in no way intends to represent the words or views of the speaker, Het Phillips.

Het Phillips has a PhD on cultural representations of the ‘Moors Murders’ and ‘Yorkshire Ripper’ criminal cases, and makes art and zines, mostly about ghosts, attraction, and industrial architecture.

Twitter: @CCLC_bham

Website: https://bit.ly/2DWj1Qg

To join the CCLC maling list please email: r.sykes@bham.ac.uk