We began our discussion of Alondra Nelson’s ‘AfroFuturism: Past-Future Visions’ by considering a quote from Ishmael Reed:

‘Necromancers used to lie in the guts of the dead or in tombs to receive visions of the future. That is prophecy. The black writer lies in the guts of old America, making readings about the future.’

Reed’s words provided a productive springboard for the questions Nelson’s text raises – particularly her discussion on the pressures of black culture being confined to a social realism, with the objective of ‘keeping it real’. Nelson notes how a long tradition of social realism in black creative life has fostered a ‘cultural environment often hostile to speculation, experimentation, and abstraction’. The spectre of Reed’s necromancer and the idea of a prophetic literature, re-reading both the past and future, redressed the fixed realist forms that Nelson critiques.

To expand upon these forms of realism, Nelson espouses AfroFuturism, a term that was coined by Mark Dery in his essay ‘Black to the Future’, as an attempt to explore the intersections between race and technology. The emphasis on intersectionality is reflected in Nelson’s insistence on the fluidity of AfroFuturism. Rather than defining it as a fixed ideology, Nelson argues that it is ‘neither a mantra nor a movement, AfroFuturism is a critical perspective that opens up inquiry into the many overlaps between techno culture and black diasporic histories’.

We discussed the ‘possibility of becoming’ that AfroFuturism promises, in terms of its capacities for reconfiguring and creating identities. Nelson writes that, ‘alternative AfroFuturist narratives insist that who we’ve been and where we’ve travelled is always an integral component of who we can become’, opening up the speculative spaces for ‘new icons, new heroes, new futures.’ From these forms of self-reinvention we discussed personas and masks, and the music of MF Doom.

From the self-styled supervillain persona of Doom, we considered crossovers between AfroFuturist aesthetics with mainstream culture, such as the Marvel film Black Panther, which in turn raises the question of assimilation versus radicalism. Following the thread of Black Panther’s American-centric worldview, we also considered how AfroFuturism might similarly be restricted to an American configuration of black experience, echoing some of the aspects of the Ta-Nehisi Coates/Cornel West debate.

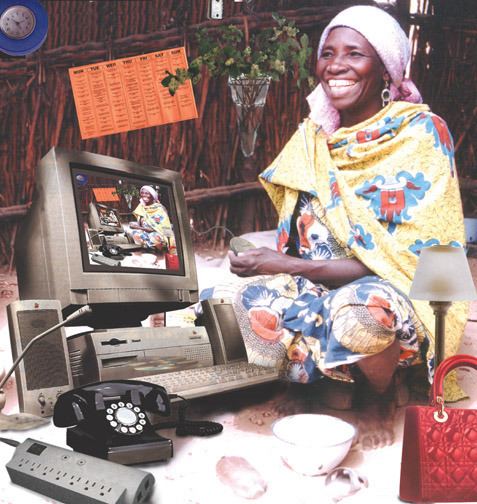

Nelson expands beyond an American conception of AfroFuturism by exploring the works of Nigerian-born photographer Fatimah Tuggar and her ‘cyborg realism’. Tuggar photographs quotidian scenes before digitally imposing additional, often technological images over the top. The result, Nelson argues, ‘is a body of utopian, and sometimes dystopian, reflections on Africa and modernity’. Afrofuturism as a concept similarly seeks new ways of expressing utopic and sometimes dystopic tomorrows, which act as necessary alternatives to neocolonial developments in the modern world.

1 thought on “Contemporary Theory Reading Group – AfroFuturism (22/10/2019)”