Following an introduction from Birmingham’s Professor David James and Dr Rebecca Roach, Jessica Pressman, Associate Professor at San Diego State U, kicked off her online CCLC event about how books and our relationship to them give meaning to our lives in digital media. Through an expansive presentation that covered what and how we read, the critical landscape of book history, and the role of close reading today, Pressman talked us through the inspirations and ideas which formed her new book, Bookishness: Loving Books in a Digital Age (Columbia University Press 2020).

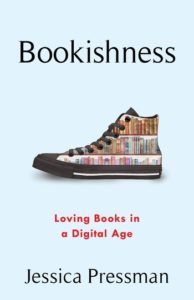

Pressman’s talk was grounded in the belief that books matter. Books, Pressman said, are the material embodiment of valuing, and as she spoke, her love for the material object – both in its symbolic and physical state – was evident. ‘Bookishness’ refers to a fetishized focus on textuality and the book-bound reading object, where the book has become an object and symbol. Pressman stretched the boundaries of what deserves our close attention with the simple and exciting answer: everything. Throughout the talk, Pressman nodded to numerous examples of bookishness and book fetishization today: the bookshelf print trainers on the cover of Bookishness; Pride and Prejudice themed PJs; bookwork sculptures; book phone covers; novels with books as protagonists; and books which fetishize paper and print thematically and formally like The Raw Shark Texts by Steven Hall. Today, Pressman stressed, the book and new media exist simultaneously.

What made Pressman’s argument so compelling was how she deconstructed the boundary between digital and material worlds, melding them so that they exist in tandem. Pressman was quick to note that despite our technological advancements and innovations which could render the object of the book unnecessary, we still so dearly love it. Last week, the Guardian reported how the publishing house Bloomsbury have seen a huge jump in bookselling profits, citing how people had “rediscovered the joy of reading” since the pandemic. The rise in book sales this past year has often been attributed to the desire to escape from the digital saturation we are experiencing, with people turning instead to the material book. However, Pressman underlined the value of books through their material embodiment and a love for the material object, which, in turn, she said, is indebted to digital culture.

In the material book’s resurgence, we have seen a reappreciation of “old media” and its blending with new forms. Taking seriously both the book and the role of technology, Pressman showed us that books change the way we look at literary and new media studies. The event made me think of the literary festivals that I write on for my own research. These festivals, which have been forced online since 2020, reach back in time and cling to a romanticised aesthetic of books. Pictures which pervade the festivals’ Instagrams are of ancient libraries, cracked book spines, and roses made out of book pages (à la Hay Festival), in an act of what Pressman called “demediating the codex.” It seems that without the live in-person events, the festivals have reached towards a new level of fetishizing the book, as well as fetishizing presence and reading. Turning the book into an art object and making us look at books different, it can certainly be argued that there has been a turn recently towards a nostalgia for material things in a digital age.

Performing the very thing that was she was talking about, Pressman’s CCLC event remediated books into objects which can be close read in an interdisciplinary way. Dr Roach offered her experience of reading Bookishness with her students this year, noting that it prompted them to accommodate kitsch, nostalgia, and attachment in their work, opening up the possibilities of discussion and analysis by being permissive of close reading the things that you like. Pressman implored us all to be, as cultural critics, more generous to those people that are consuming books. Instead of creating boundaries and drawing battlelines by pitting Art vs. The Marketplace, we should embrace both and find the literary in all. The “ishness” in bookishness was not just about aesthetics, Pressman said, but about identity and community formation. What cannot be forgotten is that books enable social interactions, they are social facilitators, and this event was a clear example of that. There is a vocabulary created for literary identification, where the subject of bookishness enables us to talk about our experiences with books, which is, after all, why we are all doing this. Because we love books.