Earlier this year I undertook an industrial placement at a very large steel company. I can remember my first day of placement very clearly. The moment I arrived I was greeted by a woman named Lesley, a metallurgist who informed me that she would be my boss and mentor throughout my placement. She showed me over to our office where she explained to me the roles of each team within our department, and introduced me to the department head, another metallurgist named Laura. My boss then walked me through the entire office, introducing me to each team and each person individually. As I shook hands and tried to remember names and faces, I quietly made a mental tally: almost one woman for every man. I was shocked.

In my A-level classes, I was used to being outnumbered by boys. In year 12 I was one of three girls taking physics, and we would sit close together surrounded by a classful of 30 lads. The science faculty were delighted we were there, simply because we were girls, and started all these ‘initiatives’ to make sure we stayed: “Women in Science” workshops were organised on our behalf; we automatically had a place on every science school trip; special meetings were regularly organised to track our progress. By year 13, two of us girls got disheartened by the high expectations and dropped physics. Luckily, I decided to keep going.

Once I reached university, my spirits were lifted to see the ratios had improved somewhat: approximately one woman for every two men on my course. At the time, it was the highest proportion of women to men out of all other engineering disciplines in the university, and I would proudly declare this fact to anyone who would listen. We even had one female lecturer, who went on to become Head of School in my second year. But my mentors and supervisors at university were still all men.

So to come into an established engineering company and see so many women represented was a huge excitement for me. That’s because I had gotten used to my chosen subject being a “male subject” – but here I saw a whole department challenging that perception. I’m sure I’m not alone in this fact, but I can’t help but compare myself to women who have “made it”, and it was fantastic to suddenly have so many positive female role models to look up to. I know that I may never have chosen to pursue engineering if I hadn’t seen myself represented in those countless ‘women in science’ seminars at school.

The changing gender balance is all thanks to the women who came before us, who have been changing attitudes so that this current generation can be inspired to join in. Conversations with female colleagues about their experiences largely describe overcoming the cultural barriers of the discipline; of constantly having to deal with comments about gender, or trying to make yourself heard in a culture that is used to being led by men. Slow improvement is being made thanks to the efforts of so many, but we’ve also got a long way to go: many of my friends can relate to an experience I had in freshers week, when a course-mate told me that the only reason I was good enough to be on the course is because “they need enough girls to make them look good”.

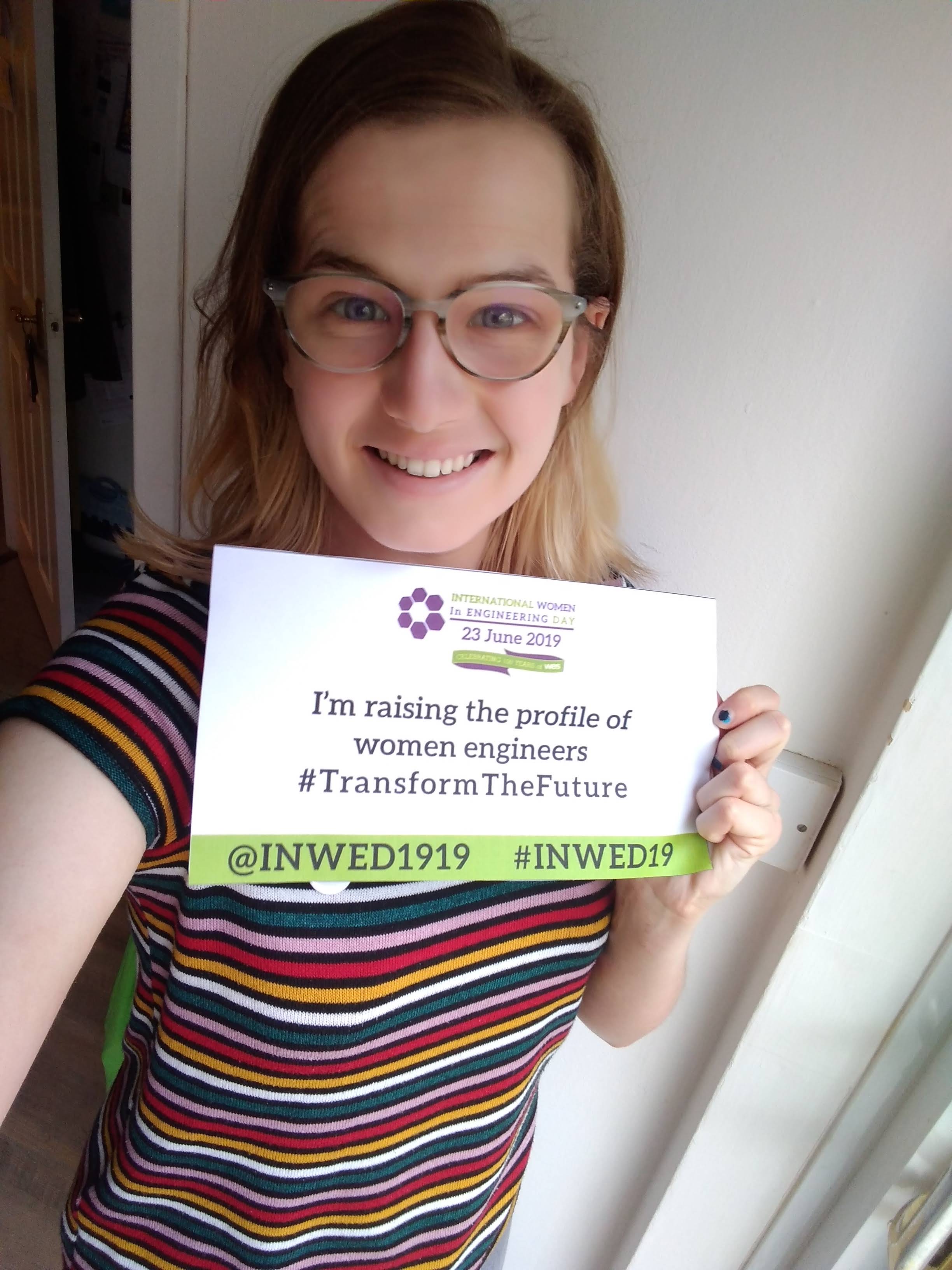

Sunday 23rd June is International Women in Engineering Day (INWED). Women have such a huge and valuable part to play in our planet’s technological future – just as much as the men – whether that’s working on the shop floor, researching in a laboratory or leading from the CEO’s office. For INWED this year, I will be thanking all the women in engineering who, just by being who they are in their discipline, are working to make the path easier for our future girls to join in, and I’d like to invite you to do the same! And if you are a young woman considering an engineering career, I’d like to leave you with the words of my course-mate describing her experience at an all-girls school: “There was no questioning as to whether females should be doing engineering, because if we didn’t, who would?”