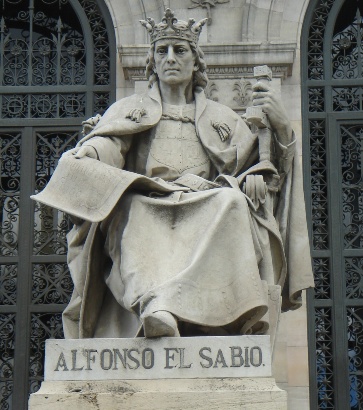

Every so often we come across personalities who are said to be “ahead of their time”. Leonardo da Vinci, Mary Wollstonecraft and Franz Kafka are some that first come to mind. But there is another historical figure whom I have grown to recognise through my postgraduate studies as a man ahead of his time: Alfonso X the Wise. Alfonso (1252-1284) sat on the throne of Castile-Leon, his realm stretching across vast swathes of modern-day Spain. But what is it that makes this thirteenth-century Spanish king worthy of any great distinction?

This was no ordinary medieval monarch — he was a sovereign-cum-scholar. During his reign he spearheaded a monumental initiative to further knowledge. His Christian and Jewish scribes (often drawing on works of Arab learning) produced many books in the fields of science, law, history and poetry. It was truly a Spanish renaissance. Beyond simply sponsoring these initiatives, we know he took an active role in the composition process, much like a director of studies today’s world. His initiative paved the way for future kings to implement the Spanish language over Latin, and move towards a more centralised Castilian state. Sadly, his extensive works are not well known outside of Spain.

It is one of Alfonso’s works of historiography — the Estoria de Espanna (meaning the “History of Spain”) — that is the source I draw upon in my own research. In particular, I am motivated to find out how this chronicle portrayed Medieval Christianity’s major rival: Islam. In the year 711, North African and Arab forces crossed the Gibraltar Straits and began to conquer the greater part of the Iberian Peninsula. Muslim Spain came to be known as al-Andalus. Whilst much of al-Andalus was gradually won back by the Christians, Islam maintained a continued presence in Spain, in Alfonso X’s time and beyond. The Estoria provides extensive coverage of this important interfaith encounter. In fact the Estoria stretches right back to Roman Spain and earlier, to the time of Hercules — who is said to have had an important role in the birth of Spain. Alfonso’s history drew on material from many earlier chronicles — it is fair to say that it has a fairly hefty bibliography!

In light this Spanish “chronicle of chronicles”, I hope to give you some of the more interesting narratives that are incorporated into the Estoria, from glory to the gory: epic battles, miracles, pestilence, natural disasters, beheadings, womanizing kings… I decided to call them “tales” as I fancy these Medieval Spanish narratives can be retold as self-contained stories. After all, you can’t spell “history” without “story”!