Methodology

- Preparation of the data

- Transcription Guide

- Presentation and rationale

- Transcriptions

- Critical text

- Reader’s text

- Table of equivalences between the Estoria Digital and the Primera crónica general

The Estoria de Espanna Digital is constructed in keeping with the view that an edition is only critical if it requires the exercise of editorial judgment expressed transparently, and digital if it has functionality that cannot be replicated on paper. Parallel to these expectations, editorial practice was very much informed, on the one hand, by the experience of previous projects- most notably the Online Froissart and the Canterbury Tales-, and, on the other, by a key principle often lost to digital projects and expressed recently by Paul Spence– namely that the editorial practice should seek to separate the preparation of data and its posterior presentation. Related to this, we were also very mindful of the need to avoid taking decisions about the preparation of data that would subsequently reduce their utility for later stages of this, or indeed other, projects. Unlike the procedure adapted by other projects, the Estoria Digital aimed for depth rather than breadth of data. Thus, instead of aiming to transcribe a large number of witnesses with minimal tagging and a high degree of regularization in the representation of manuscript text, we attempted to encode as much of the material information of a limited number of key manuscripts as time would allow. The richness of the resulting data would allow a higher degree of digital access to the Estoria while also facilitating the addition of further manuscript data in the same manner in possible future phases. The methodology developed in the edition consisted of the following phases.

Preparation of the data

In the initial phases of the project, team members transcribed the five witnesses employing TEI5-compliant xml. A set of transcription guidelines were developed, primarily by Dr. Bárbara Bordalejo, and refined in the course of the project (link to Guidelines). Transcriptions were prepared by the transcribers using the Textual Communities system at the University of Saskatchewan. This tool provided transcribers with the ability to work on transcriptions of individual folios whose images were accompanied by a transcription space. An automatic parser in the Textual Communities system ensured that only correctly expressed xml was entered into the system. Textual Communities also enabled the general editor to monitor progress across all of the witnesses simultaneously. Regular team meetings and virtual consultations ensured consistency of practice.

Base text, numbering system and textual division

In parallel to the first stage of the transcription it was necessary to establish a base text (to allow for collation of other manuscripts) with a numbering system. For a variety of reasons, the text of E1 and E2 was chosen as the base text for the initial phase of the edition. This, of course, has some implications for the status of the edition, nonetheless, it was decided that using these manuscripts was the only viable option at the outset. In subsequent phases, a notional base text can of course be derived from the base established here as further manuscripts are added. The process of establishing the numbering system (and transcribing E1 and E2) was greatly aided by the existence of the Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies transcriptions; we would like to express our gratitude to the HSMS for allowing us to use these to aid our own transcriptions. The numbering system employed the <div> tag for chapter level divisions, and the <ab> for sentence level divisions. These were inserted on the base text, that is, the text of E1 and E2, and so it might in consequence be objected that such divisions are not necessarily reflective of an Alfonsine Estoria. No full Alfonsine numbering was possible, for obvious reasons, but the regular punctuation system of E1 and, to a slightly lesser extent of the 1289 sections of E2, meant that we could have a high degree of confidence in the chapter and sentence-level numbering we imposed, as we attempted, where possible, to deploy <div> and <ab> tags which respected the textual organisation and punctuation of these codices. As any manner of dividing the text -both for the purposes of reference and for collation- would necessarily have a certain element of arbitrariness, it was felt that the system chosen was the best solution.

In addition, the numbering system, while not necessarily supplanting the reference system of the PCG, does have the virtue of allowing for equivalence across all witnesses as equivalent sections in the different witnesses all have the same numbers. It is hoped, then, that this numbering could become a standard form of reference for all witnesses of the Estoria. In passing, it might be mentioned that the <div> tags in E1 and E2 allow for full cross-reference to the PCG chapter numbers, so the PCG referencing system can also be employed as a back up.

The underlying principles which informed the transcription of the manuscript text are:

Graphic elements

We attempted to represent with Junicode characters something approaching the form of the individual characters produced by medieval scribes. However, as the Estoria transcriptions are graphic and not palaeographic, we did not seek to differentiate between different forms of the same letter; as a result the transcriber was required to use her or his judgment about shape of letters and give the best equivalent available. In addition, we followed the usus scribendi in each manuscript; our aim was to represent what is on the page, and not, at this preparation stage, express a view as to what a scribe might mean. Thus, for example, we respected the length of descenders in long “i” by transcribing it as “j” even in those cases in which “i” would be expected. The initial phase therefore sought to provide digital equivalents of medieval characters without a high degree of editorial intervention.

Abbreviations

Where the transcribers (and editor) were of the view that a scribe employed an abbreviation, we employed appropriate Junicode symbols to represent the abbreviated character and the consequent xml tag to expand the abbreviation so as to indicate the editorial view as to what the abbreviation represented. (A full list is available in the Transcription Guide; the way these are represented in the various forms of edited text is properly the subject of the “presentation of data” section below.) In expanding, we again followed the usus scribendi. This inevitably led into one form of inconsistency – different expansions for what appears to be the same abbreviation in different parts of the same manuscript- but it also meant that scribal sections are internally consistent. As the materiality of manuscript text is a central part of this edition, the decision was taken to privilege where possible the scribal forms of the text and not to regularize, supply or correct any scribal forms.

Suppression marks and punctuation

In the same manner, although we represent all suppression marks, we do not attempt to differentiate between different forms of the same mark; thus, for example, we employ the standard hook ’ which represents the syllable “er” and “re” even if sometimes looks more like a macron in the manuscript. Although we recognize that this may reduce the immediate utility of our transcriptions for those interested in palaeographical issues, nonetheless the flexibility provided by digital searching tools, and the availability of (most of the) manuscript images should still permit a high degree of utility for most academic purposes. The same is true, to a slightly lesser extent given the smaller number of possible symbols, for punctuation. We have recognized the presence of punctuation marks, but without always attempting to replicate them exactly in the form of the Junicode characters employed. The way in which these are represented in the transcriptions is dealt with below.

Transcription Guide

The full detailed guide to transcription is available here.

Presentation of the data and rationale

In presenting the front end of the edition, we were guided by two central principles: (i) that the presentation of the Estoria Digital should, where possible, take full advantage of the possibilities offered by digital tools, and (ii) as stated above, that the presentation should emerge from, but not condition, the initial preparation of data. With this in mind, a number of strategic decisions were taken about the way in which the data should be available to the user, and these were necessarily different in the case of the three principal modes of access.

Transcriptions

The transcriptions are presented in two ways: abbreviated and expanded. The former is relatively unproblematic, in that we mimic, where possible, the presence of suppression marks, and therefore the medieval script – within the limits referred to above. Thus the presence of such characters as e.g. ħ, ꝑ and macrons. The latter is rather more problematic as it involves a range of editorial judgments and gives the greatest room for innovation (and controversy) in the presentation.

It might be argued that in the expanded transcriptions, there is no need to signal that editorial operations have taken place since the user has readily available the abbreviated equivalent, and also the manuscript images. The approach taken, nonetheless, is to indicate discreetly but overtly the intervention of editors in the expanded transcriptions. In part, this is to avoid giving the impression to the reader that the text on the screen is devoid of all editorial action. The main reason it was decided to do this, however, is because the digital presentation of the text allows for this without cluttering up the transcription and making it difficult to read – we therefore were aware of the possibilities of making a small contribution to pushing the boundaries in editing medieval texts.

Having decided that the expanded transcription should note editorial intervention, it remained to decide how this should be effected. The traditional mode of the employment of italics for all such editorial actions was discarded (i) because it was felt to be visually burdensome and (ii) because, in line with Paul Spence’s comments on the subject, blanket use of italics still requires the reader’s input to differentiate between different types of editorial actions.

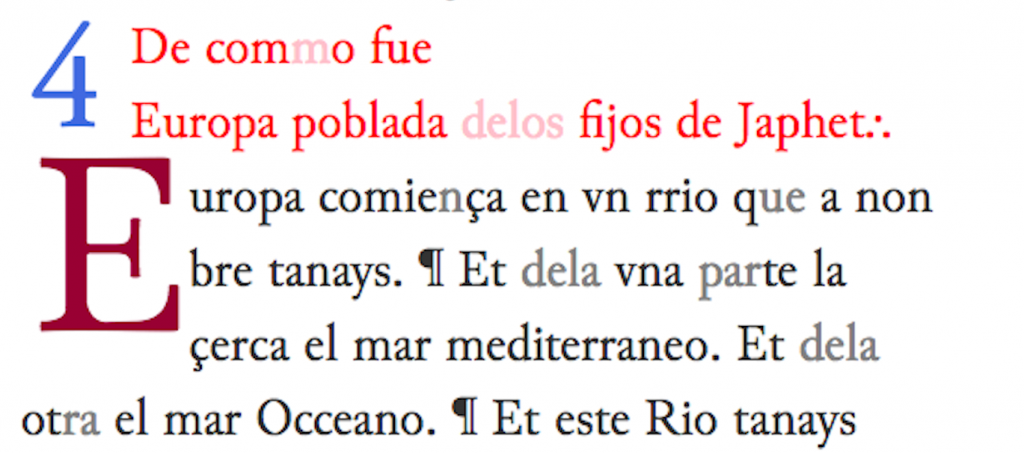

The primary aim in designing a system of presentation for the expanded transcriptions was to provide a visual distinction between what is directly presented in the manuscript and what is inferred by the editor. This, and other editorial interventions, are marked by the use of different colours, rather than fonts or typefaces. The standard black characters (or red for rubrics) serve to indicate those characters which are present in the manuscript. We employ a faded version of the same colour to indicate those character which are inferred by the editor – usually as a result of the resolution of a suppression mark. Thus the opening of chapter 4 in manuscript Q (Folio 2v) reads as follows:

Where the suppression mark is separate to another character -such as in the case of a macron over vowels- only the inferred character is faded. In those cases in which the suppression mark forms a part of another character –as in the case of ħ, ꝑ and the hook representing ‘er’, then the whole syllable has been faded.

In those cases in which there has been scribal alteration, we encode by means of the <app> tag all of the possible readings.

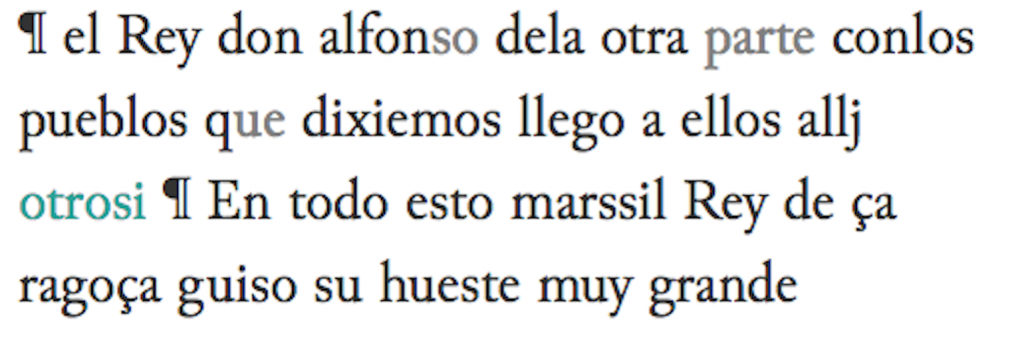

The original representation is picked out in teal, and the altered reading is available by means of a mouseover.

In the transcriptions, the basic physical features of the manuscript page (column breaks, line breaks etc.) have been respected and other bibliographical features (initials etc.) have been picked out in size and colour (though not always as an exact equivalent of the manuscript). Where the manuscript is damaged or there are lacunae, this is also marked visually.

Critical text

The critical text was prepared using a version of Peter Robinson’s CollateX developed by Cat Smith and Zeth Green in the Institute of Textual Scholarship and Electronic Editing at the University of Birmingham and put into practice with the aid of Peter Robinson at the University of Saskatchewan.

Preparation of data:

The text is a hypothesis of the versión primitiva which employs as its base text those manuscript sections that provide us with the best evidence for the primitiva. The implication of only using direct evidence for the primitiva for the hypothesis is that the edition ends where manuscript T comes to a halt –chapter 811, equivalent to PCG 800- as the remaining text in the Estoria Digital (from E2 and Ss) is not directly derived from the versión primitiva.

The base text is thus made up of:

E1 folios 2r-197r, corresponding to chapters 1-574 (PCG ch. 1-565)

E2 folios 2r-17v, the gathering of E1 later added to E2, chapters 574-627 (PCG ch. 566-616)

E2 folios 18r-21v, corresponding to chapters 628-634 (PCG ch. 617-623)

Y: folios 372v-380vr, corresponding to chapters 635-656 (PCG ch. 624-645)

T: 128r-201v, corresponding to chapters 657-811 (PCG ch. 646-800)

The fragment from manuscript Y was used as neither E2 nor T has testimony directly drawn from the primitiva at this point. The resulting text is therefore a variant edition of the transcriptions of these sections from the manuscripts.

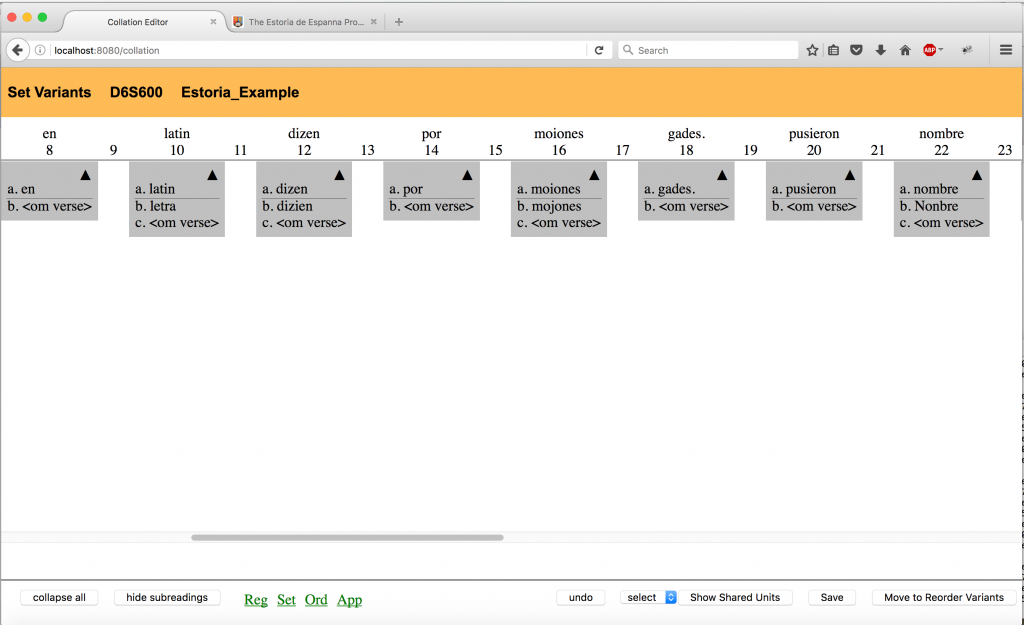

The manuscript witnesses were collated against these base text sections. The aim was to maintain only those variants which were considered to be stemmatically significant. Thus, all variation which was considered to be solely orthographic was regularized out. In the example below, the variants from manuscript Q in blocks 16 and 22 were therefore regularised. Toponyms and anthroponyms were considered to be an exception and were not regularised except in cases of variation in the shape of letters. The variants are therefore fundamentally those of alteration of word order, verb form or lexical choice.

As the object of the exercise is not to fix the Estoria, but rather to allow it breathe in its textual diversity, the adoption of these conservative principles of collation was considered necessary. If it is indeed the case that, in the words of David Parker, the object of the exercise is the removal of “noise”, it is not quite clear that what constitutes that noise is the same in all editions. In the case of the Estoria, the absence of an authorized base text against which to collate, at least for now, meant that it was necessary to be quite circumspect in the regularization phase.

A more detailed acount of the collation principles can be found in Aengus Ward, “The Estoria de Espanna Digital: collating medieval prose – challenges… and more challenges”, Digital Philology (forthcoming).

Presentation:

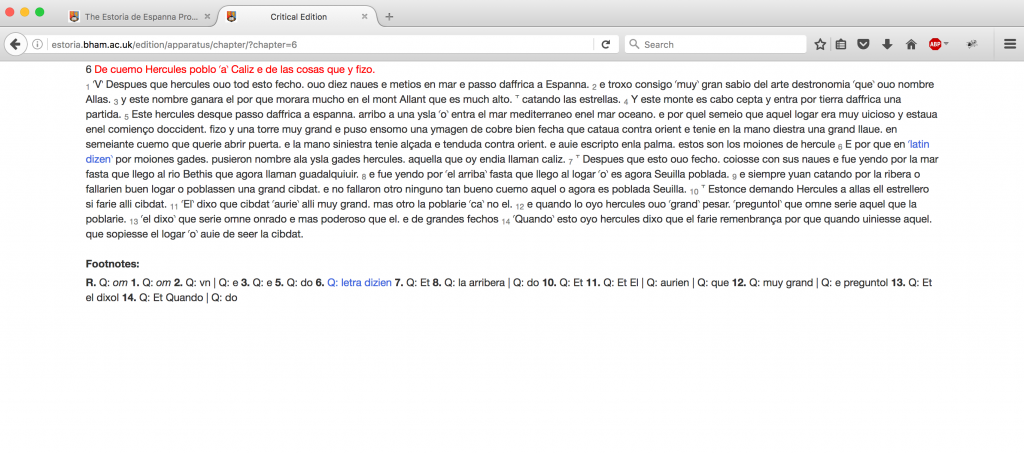

The presentation of the critical text follows the same principles as that of the transcriptions: the edition should take advantage of digital tools to present the Estoria in as reader-friendly a way as is possible without compromising the nature of the text. The following is the result of the collation made above:

In the critical text, since the edition is not formally tied to a single manuscript, we do not attempt to mimic manuscript layout; the text is presented in a single column, with footnotes containing the variants. As previously, the rubrics are picked out in red. We have attempted to reduce as much as possible the clutter on the page, so we have not used insertion marks beyond the traditional footnote number. A mouseover on the text indicated by the footnotes alters the colour of the fragment concerned and also that of the variant in the footnotes (block 10 from the collation is highlighted here). In recognition of the diversity of manuscript text, but also of the necessarily provisional nature of the edition, we have not sought to impose any regularization on the critical text; the orthography and punctuation remains that of the base text throughout. For similar reasons we do not replace base text readings with those of any variant judged to be better; this is an editorial operation which goes beyond the principles of the current edition.

Reader’s text

To accompany the critical text, and in recognition of the requirement from many users for a regularized and punctuated version of the Estoria, we also provide a version of the same base text of the primitiva but without any variant readings and presented in such a way as to facilitate reading for a modern readership. It should be noted that because this is based on a transcription, and not an edited text with preferred readings, it contains some manuscript readings which in a fully edited text would be considered defective. The full criteria used in establishing this regularized version are available here.