This week, we are half way through the initial experiment in transcribestoria, so I thought it might be a good moment to reflect on what we have done to date, to answer a few queries that have arisen in the last few weeks, to clear up a few questions about the ethical stance of crowdsourcing and to tell you a little bit more about what we would like to do in the future.

You are probably sick of hearing me say that (i) this is a pilot project and (ii) we are very grateful for your input. This is all true, despite the repetition! The aim of the project is first and foremost to see if there is a public interest in medieval Iberian manuscripts – the fact that we are now at 300 signups suggests that this is in fact the case, so that will help us to develop our projects in the coming years, and we will be committed to continuing our crowdsourcing ventures in some form or another. The subordinate aims were to create a series of training materials which would demystify medieval manuscripts and allow non-specialists to access images of original materials; and eventually, perhaps, to involve a wider public in the compilation of our research materials. The numbers accessing our YouTube channel suggest that the first of these has been a success, but the second is a long way in the future.

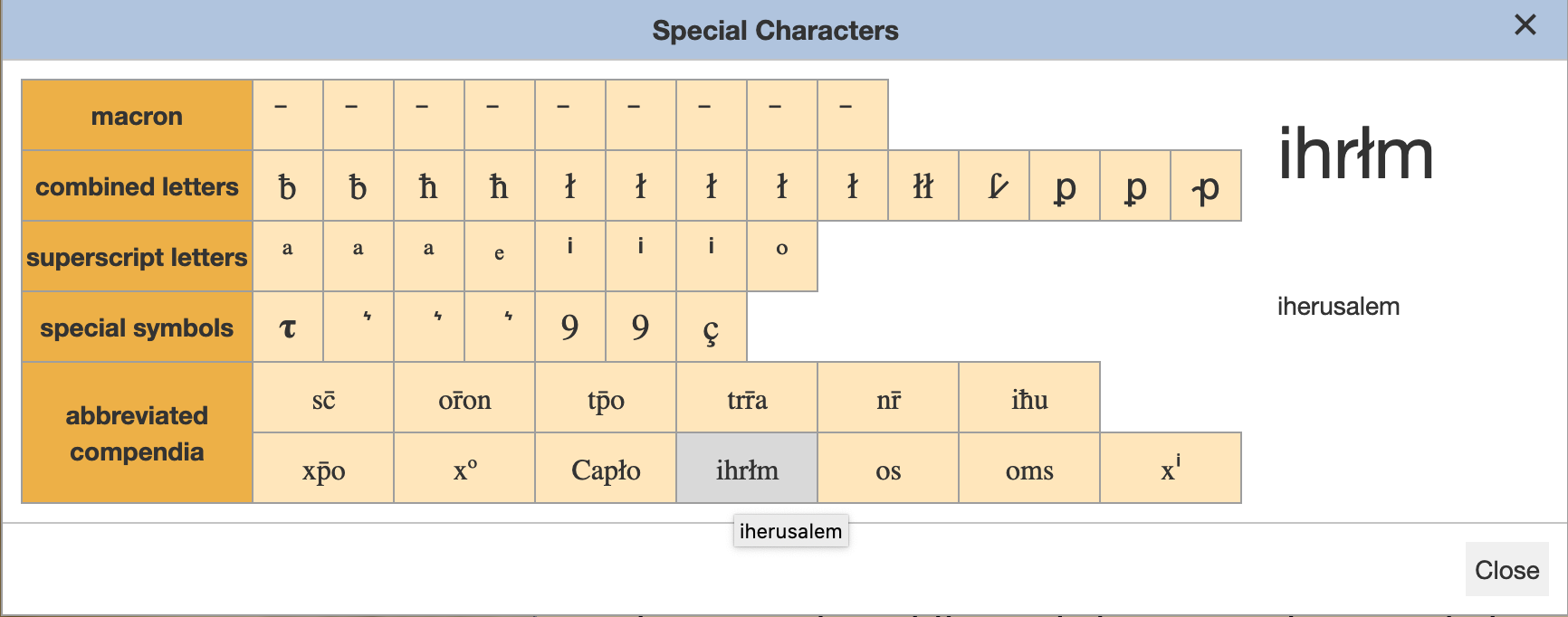

We have learned a lot from you all in these five weeks. Thanks to your transcribing, you have told us about defects in our systems. In particular, notification of the absence of key characters in the abbreviations palette has been especially useful for us. Amongst others, for example, we have recently added a hot key for xⁱ -> “crist”, or a hot key for “ç” for those whose keyboards might not provide an easy way to type this. There is always a tradeoff between the desire to represent as much as possible, on the one hand, and the use value (or indeed practical ability) to do so, on the other. There is a particular irony, given how much we have been haranguing you on the necessity to distinguish between “i” and “j”, that the expansion for ihrłm -> ierusalem is only possible with “i”. These are the kinds of lessons we will find very useful for future incarnations of the project.

Ooops…!

Where do our transcriptions go?!?!?

If you are interested in what we are doing with all of your transcriptions, I can give you a little hint. Initially, we use the transcriptions you provide to allow us to see how you are all getting on. We have transcribed these passages ourselves, so we compare your xml output with our own corrected versions to see where you are making mistakes or are having difficulties. From this comparison, Polly and Ricardo have extracted the most common difficulties, and these form the basis of the posts we put up in week 2 and week 4 to tell you how everyone is getting on. As we have said before, we did not anticipate that so many of you would sign up, so we were unable to give individual feedback, but we anticipate doing this in the future as the project develops. Our transcription desk does allow for the possibility of having a corrected text which would make an automatic comparison with the user transcription and give instant feedback. As we are just at the pilot phase, this is not fully developed yet, but if we do put the project on a firmer footing in future, this is certainly one of the features we will add. That way, each transcriber could have individual feedback. Of course, this would require the pre-existence of a correct version of the transcription, something which is not unproblematic.

The main objective of the current project is to get a wider group of people interested in medieval manuscripts and to demystify the beautiful objects we work with; thereby making them more accessible and understandable to a wider public. We are doing this with five short sections of manuscript C, but the remainder of the codex is not yet transcribed. In mid-November, we will put on our transcription platform the first 50 folios of the manuscript. If you choose to transcribe these, the resulting xml may at some stage be incorporated into the digital edition of the Estoria de Espanna. The secondary aim of transcribeestoria is for us to see if there is a sufficient group of people interested in the next stage – that is, participating in the original research into the Estoria de Espanna by helping us to transcribe the manuscripts which are not yet included in the edition.

The xml files that are generated by your transcriptions will be very useful for our research, but we cannot incorporate them directly into our edition.

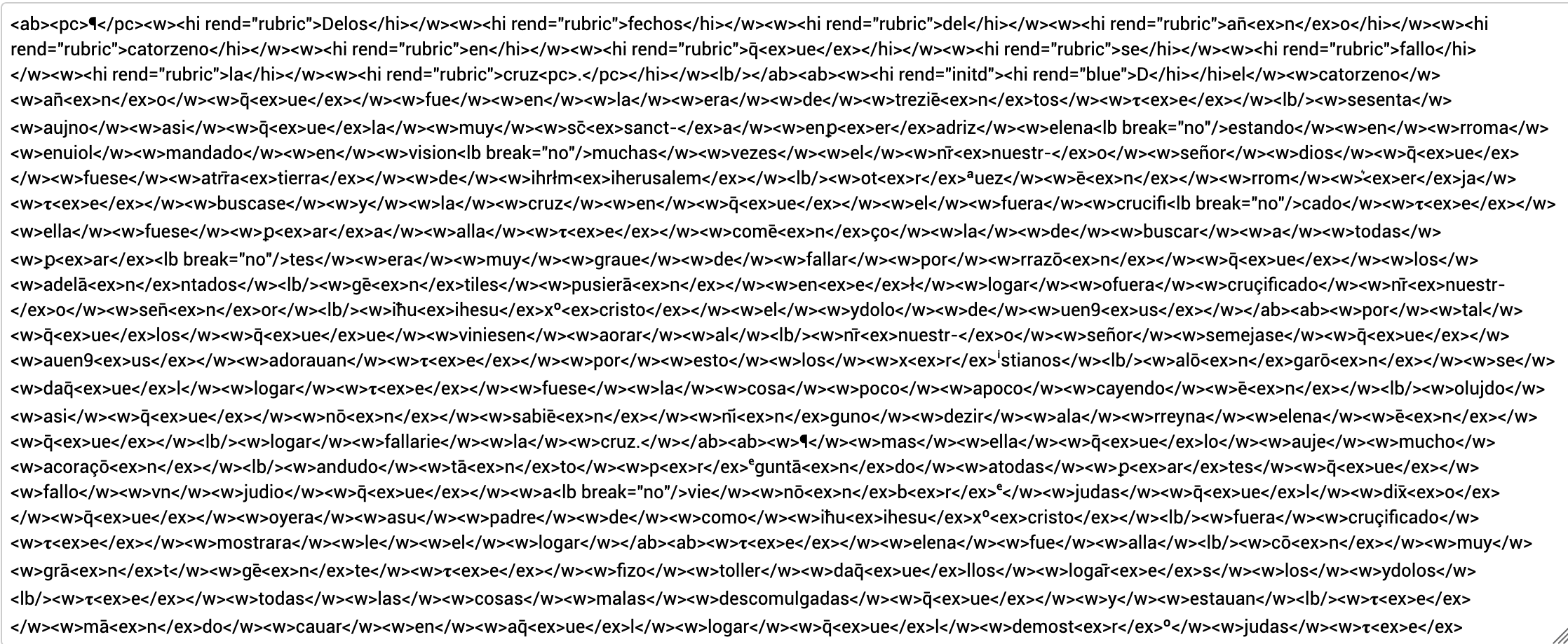

Here’s an example of the output of one of the current transcriptions:

It is saved in xml format; this is a markup language which is designed to be readable both by humans and computers. Digital humanities projects use a version of this, a dialect, if you like, called the Text Encoding Initiative, or TEI. The basic idea is that anything significant is enclosed between two tags: thus, for example, what you mark in the transcription as a q with a macron over it, appears in the xml as: q<am>̄</am><ex>ue</ex> where whatever appears between <ex> and </ex> means “this is what the previous abbreviation mark expands to”. It’s all supremely logical, if a little difficult to follow at the beginning.

All of our transcriptions then, are saved in TEI5-compliant xml (althoiugh, for the moment we are using a more simplified version than that used in the Estoria de Espanna Digital). But fortunately for you, transcribeestoria is a wysiwyg (What You See Is What You Get) system – this means that Cerys and the team at BEAR here at the University of Birmingham designed a system which allows you type what you see, and the code turns this into xml which we can use for our research.

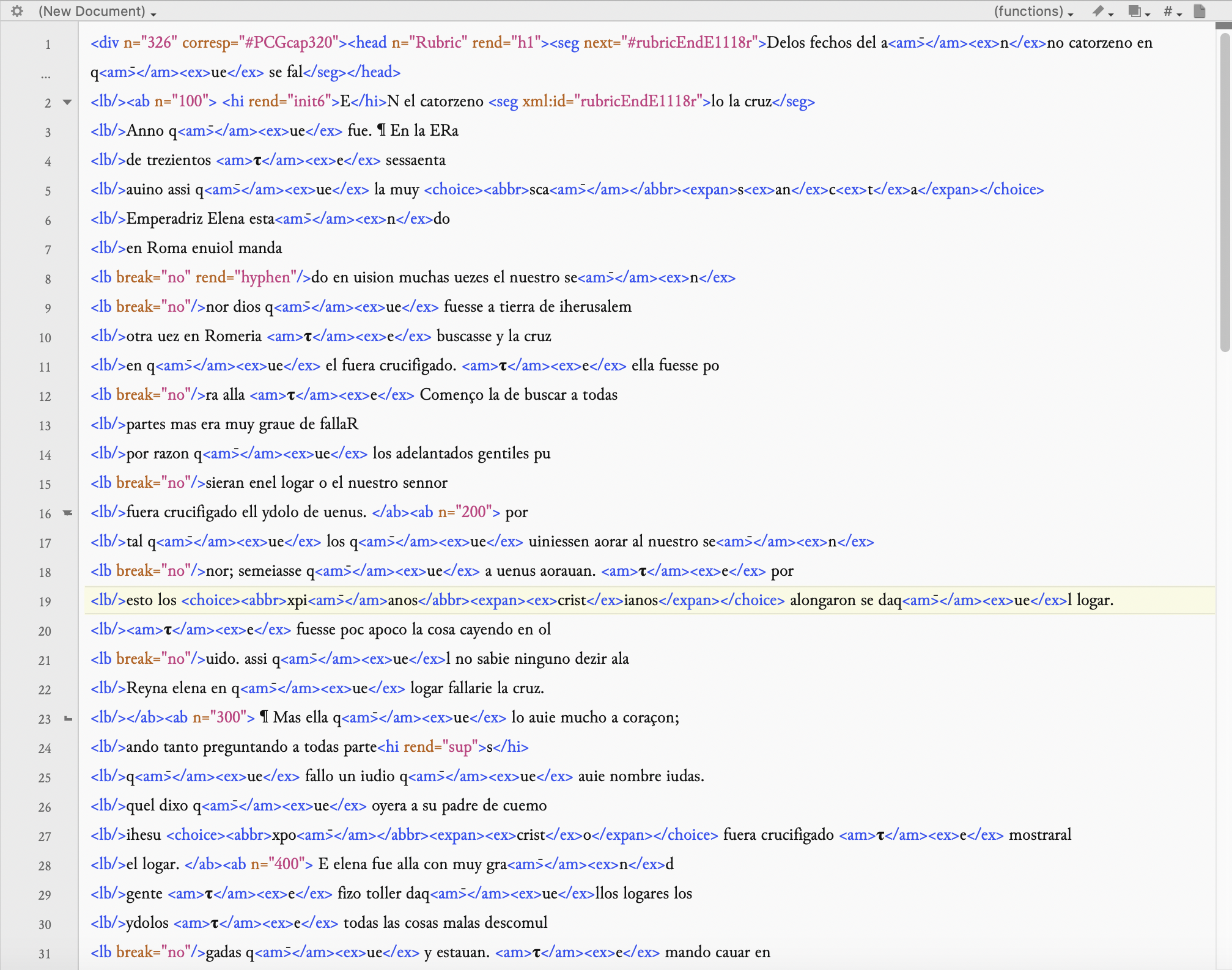

As you can see, the coding behind the transcription is very detailed – in fact, it even differentiates between individual words -which are encased in the <w></w> tags. The following image is the xml file of the same passage in E1 from our edition. As you will see there are some differences:

The most obvious difference (apart from the absence of <w> tags> is the presence of numbers in the edition text. These tell us, for example, that it is chapter 326 of the edition <div n=”326″>; they also tell us the numbers of each of the sentences of the chapter. We have numbered all of the sentences of the entire chronicle (you can see them in the edition), because this creates a standard way of referring to any part of the text, whichever manuscript is being read. Thus, for example, by searching for 326.2 in any manuscript, you will get to the same sentence in different witnesses – the sequence beginning “por tal que los que uiniessen aorar al nuestro sennor“. Doing this also allows us to collate all of the witnesses of the Estoria, and thereby presenting in one digital “place” a comparison of all of the evidence for the Estoria. But if you do go on to transcribe “freestyle” for us (and we hope you do!) we would have to add in all of the numbers afterwards – because the transcription desk we are using at present cannot include these numbers (we won’t bore you with the reason why…).

Crowdsourcing: free research in the days of the gig economy?

In an extensive blog post a few weeks ago, Polly addressed the rationale for crowdsourcing. I appreciate that there is some unease, especially in the research community in Spain, and especially amongst Early Career Researchers and/or postdocs, about the ethical basis for what we are doing. We have all heard horror stories of the legwork of early career scholars being incorporated into major works without any public recognition. In the first instance, I would like to point out that all transcription carried out by volunteers in the original Estoria de Espanna Digital project was appropriately recognised in the acknowledgements of that edition. Were we to be in a position to incorporate any volunteer transcriptions (although as mentioned above, we are very far from that at present) the same would also apply. Our aim is to expand knowledge and understanding beyond academic communities -we have tentative plans to approach centros de mayores in future, for example, to see if there is any interest in involvement there. But at the same time, it would be foolish to pretend that there is not a serious issue here, but the intention is very much NOT to exploit the free labour of researchers who may feel they have no choice but to take part. I am aware that this is a very common phenomenon in the twenty-first century economy and I would not like to see this extended to academic labour.

Future plans

As we reach the halfway point of transcribeestoria 1.0, the thoughts of all of us here inevitably turns to what we can do next with the tools that we have developed. It may be that crowdsourcing of this type will have a short life, particularly given the rapid development of Optical Character Recognition software which will aim to provide automatic computer-based transcription of manuscript text (see transkribus.eu for an example). But the human element of this project, bringing us in some way closer to the traces of our past and helping us all to understand them, will remain. To this end, we have tentative plans to collaborate with libraries which hold other manuscripts of the Estoria in a much wider crowdsourcing project. Do let us know if you would be interested in taking part and/or spreading the word.

And good luck with the ongoing transcribing! The next text, released on the 13th November, will deal with the origins of Islam as portrayed in the Estoria. And we will release the opening of the manuscript for anyone who wishes to go freestyle!

Aengus

1 thought on “Transcribeestoria – lessons learned half way through”

Comments are closed.