Welcome to the second of our passages. This one is about the emperor Trajan. If you were wondering what this might have to do with the history of Spain, it’s made pretty clear in the opening lines – according to the chronicle he was born in Extremadura!

This is the translation of the passage,and we have included a few lines at the end, because the image of the manuscript in the transcription desk ends where we have put the ** in the text below. If you would like a regularised Spanish version of the text, you can find it in the Spanish blog post we publish today, and of course you can also find it at the Estoria de Espanna Digital edition – it’s chapter 195.

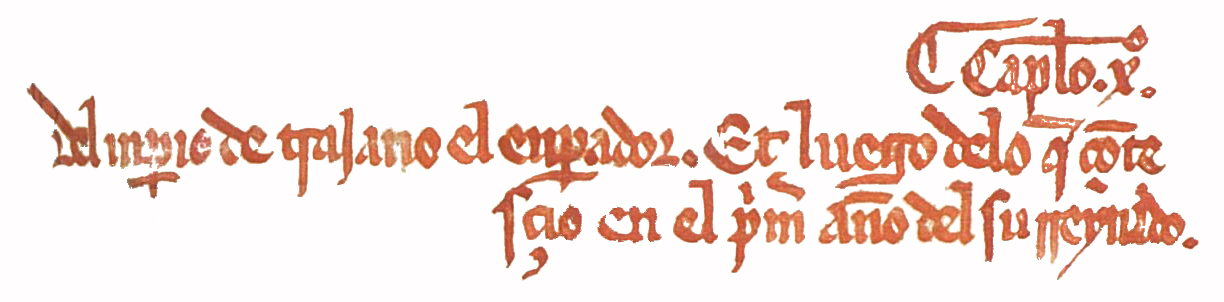

195 Of the empire of the emperor Trajan and then of what occurred in the first year of his reign.

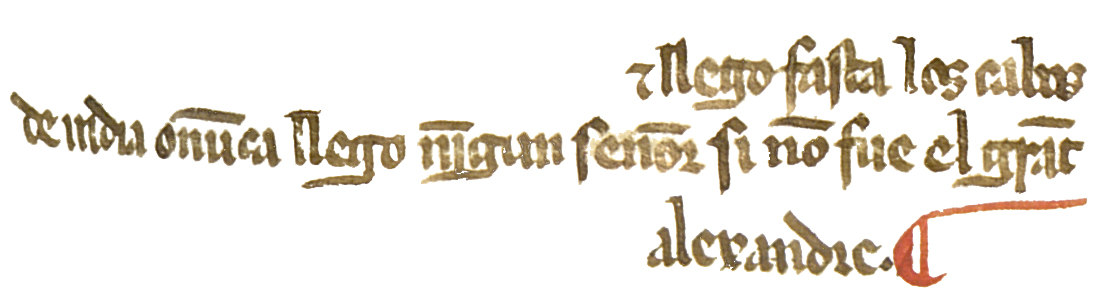

1 After the death of Nerva, Trajan, whom he had adopted, was raised as emperor of Rome.2 And the first year of his empire was eight hundred and twenty six years since the founding of Rome, and in the era of one hundred and thirty eight years, and in the year of Our Lord one hundred. 3 This Trajan was Spanish, as it says above, and he was from a town in Extremadura called Pedraza. 4 And they called him Trajan because he was from the lineage of Troy who had come to inhabit that land, for his name was Ulpio Trinito, and Trajan by surname. 5 He received the lordship and nobility of the empire in Agripina, a city in France, and he reigned for nineteen years. 6 Trajan was very honest and very companionable to his friends, and he greatly loved the knights and was mild to the citizens, he was loyal and sincere in freeing the cities of tribute; and because he restored and rebuilt Rome following the great destruction that had preceded his reign, the people said that they had been given this emperor by the grace of God. 7 As soon as he was emperor, he conquered all of Germany beyond the river they call the Rhine 8 and he defeated many peoples beyond the Danube; and he turned all the lands of the barbarians who live beyond the the rivers Tibre and Eufraten into provinces of Rome; 9 and in the end he took Seleucia and Babylon and reached the borders of India where no other lord had gone, with the exception of Alexander the Great. 10 One day, it happened that this emperor Trajan was going out to battle, and he mounted his horse. 11 As he was leaving his palace, a widow appeared before him and grabbed his foot, weeping. And she begged him to give her justice against some men who had wrongly killed her son, who had done them no harm, nor sought any ill. 12 And she said to him: “Oh great emperor Augustus, behold the terrible wrong which has been done to me”. 13 And Trajan said to her: “I will do you justice when I return from the battle”. 14 To which she replied: “And if you do not return, what will become of me?” 15 He said to her: “Whoever is emperor after me will right this wrong”. 16 And the widow then said: “But how can I be certain of this? And if it is this way, what benefit will come to you for the justice another might do?, 17 for it is you and not another who is my debtor, and you should have recompense only if you deserve it; you will deceive if you do not give me my due. 18 The emperor who follows you will be bound to do justice to the complainants but another’s justice does not free you of your obligations, for your successor will only release himself, and not you, of his obligations.” 19 And when Trajan heard this, he was moved and he took pity on the widow, and he dismounted and heard her complaint and he gave her the justice she deserved. 20 Know also that Trajan had for his guardian and master a great philosopher called Plutarch, who guided him through words and books so that he was of good customs and led the empire well. 21 This Plutarch had a servant who was well versed in all of the seven arts. 22 On one occasion, for something that he had done, his master tore his tunic from him and began to strike him with some reins. And the servant began to deny that he had done what they said. But when he saw that this was not working, and that he was being struck even more, he began to beg mercy of his master, and to tell him jokes so he should laugh. 23 Amongst other things, he said: “This is not how Plutarch the philosopher should be, 24 for it is an ugly thing to become enraged, especially for one who argued so many times about the evil that comes from anger, and who wrote a book about how suffering is so good a thing. 25 It is a vile thing indeed for a man to fight for customs when he teaches the opposite to others, 26 just as you are doing now, my lord, for you have allowed the understanding of your heart to contract and you have been overtaken by anger so that you are cruelly wounding your servant who is without fault”. 27 Then Plutarch answered him calmly and slowly and said to him: 28 “Perhaps it is that I seem angry to you because of the blows that you receive, or that I am angry for doing to you what you deserve. 29 Can you see in my face, or my voice, or in my colour, or even in my words, that I am angry? For it seems to me that I am not. ** 30 For my eyes are not wild, nor is my face twisted, nor am I shouting without control, nor is my face red. I have no spittle coming from my mouth nor am I saying shameful thing for which I would later have to repent, nor am I trembling with anger. For if you do not know, these are the signs of anger”. 31 And as he was saying this, he turned to the man who was thrashing his servant by his order and said: “While he and I are debating, keep doing what you are doing, and without anger from me punish the rebellion of the servant, so that you show the evil one how he should repent and not debate with his master”.

Of course, the fact that Trajan was born in what is now Spain, is not the only reason that this passage is in the Estoria. The compilers of the history clearly regarded Roman history as being fundamental to what they thought of as the narration of the past of Spain. The relationship of the Roman Empire to Alfonso’s own political plan is the subject of a guest blog post next week by Elena Caetano Álavarez.

This chapter, dealing with the opening section of the reign of one of the greatest emperors, has a number of interesting features which you might like to consider. First, there is the chronological and personal information at the beginning. This all gives the Estoria de Espanna its coherence and structure – you will see this structure, with particular emphasis on dates, all through the chronicle. You might also be interested in the particular dating systems employed. Second, there is mention of Trajan’s accomplishments byond the Rhine and the Danube, and reaching even as far as India. The comparison that is made with Alexander the Great is important. You might like to think about what this says about Trajan, and indeed the history of Spain.

Third and fourth are two anecdotes – one involving a widow, and another involving the philospher Plutarch. These self-contained stories are woven into a singular narrative of the Empire, and therefore, implicitly, of Spain. They are also a reminder that one of the functions of history is that of entertainment – we all like stories and they form an important part of our cultural background. Let us know what you think of these two anecdotes, and why you think they might be here.

While you transcribe, have a look at the image closely. There are a couple of things that you might notice. To begin with, the colour of the page is not like paper. There is a reason for this, of course, and it relates back to something we mentioned in the first training module. But there are also additional features – note the faded text in the middle of the left column (lines 4-5 after the rubric), or indeed the additional writings on the page. These will be one of the subjects of our next blog post, but if you want to talk about these while you wait, then add some comments to this post – or tweet us at @EstoriadEspanna (or Facebook).

Remember you can go on to look at other passages if you wish. Eventually we would like to transcribe the whole manuscript.

1 thought on “Text two: Trajan the Spanish emperor”

Comments are closed.