Continuing our occasional series of posts looking at medical devices from a historical perspective, Kevin Matthew Jones surveys newspaper coverage from the early 2000s, finding devices linked with national identity, culture, finance and fame.

In the first of my blog posts, I outlined the research I have conducted with the Everyday Cyborgs 2.0 project on newspaper articles held by the British Library’s British Newspaper Archive. Looking at how ‘medical device’ featured in articles between 1945 – 2000 provided clues as to how the word constructed cultural meaning and operated at the boundaries of medical, economic, and social discourse. In this second blog post, I will discuss observations from the second round of research, coding data from articles dated between 2000 and the end of 2004. At first glance it may seem strange to divide the research in this way, but the dataset is quite imbalanced: the first 900 articles that I discussed in my first entry run from 1945 until 2000, but the next set of 1184 are from a four year period between 2000 and 2004. Aside from 2000, the spread of these articles is fairly evenly distributed, ranging between roughly 200-250 articles per year.

In this second stage of my research, the greater proportion of the news stories mentioning ‘medical devices’ are pulled from the financial section of local and national newspapers. The story that these articles tell is one of investment capital intertwined with technology of the clinic and national identity and economic fortunes. The ways these themes were raised in current affairs surrounding medical devices shed light on the complex social and cultural meanings that the term accrued. As discussed in other Everyday Cyborgs posts, the Irish context is particularly well represented in these archives (indeed after 1999 virtually no UK-based papers are available in the BNA). I will therefore continue pursuing this focal point.

Although the observations below on the intersections of medicine, economics, and the state are derived from the Irish case study, a lesson that we can take from it is that medical devices often function as a boundary objects. In later clarificatory work, Star wrote that one of the defining characteristics of a boundary object is that they are ‘a sort of arrangement that allow different groups to work together without consensus.’ Boundary objects set up a ‘shared space’ between different interests, and part of what allows them to do this is their ‘interpretive flexibility’, or how the different interest-based demands placed upon the object govern how they are viewed. Star uses the example of maps: for some they may represent possible camping sites, for others they may represent suitable grounds to collect biological data, yet others may be concerned with identifying geological features for study. Through their interaction with the map and by extension the landscape, these groups are all implicitly connected without being in direct communication.

In the case of medical devices, investment groups, clinical practitioners, and state-agencies interact in indirect ways. My last post outlined Ireland’s emergence from the late eighties onwards as a European leader in the manufacture of medical devices and this continues between 2000 and 2004. Throughout the nineties, there is frequent coverage of foreign companies bringing well-paid and ‘clean’ jobs to the new technology parks that had been set up by Ireland’s Independent Development Agency (IDA). These efforts attracted hi-tech industries to areas such as Galway and Mayo, and were frequently covered in the press. The cultural connections to the United States were also frequently covered and aside from a few scandals during this time, medical device manufacturing was generally covered in a favourable and positive light during the 90s.

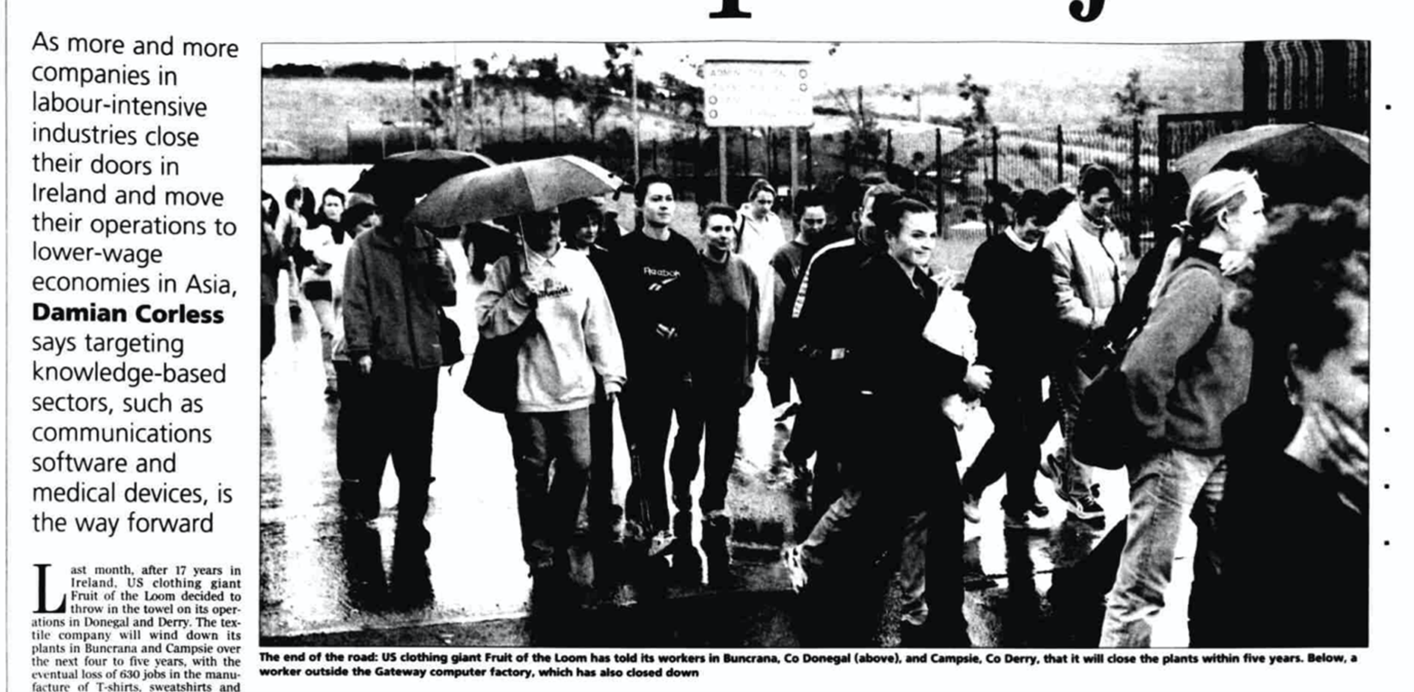

This continued after the millennium as medical devices came to be viewed as providing a reliable backbone to the Irish economy. Some even viewed clinical technologies to be the country’s saviour as other parts of the industrial sector faced creeping job losses and downturns. Even high-tech industries weren’t safe: stories relating to the sector saw a marked increase in 2002, perhaps because of coverage of the dot.com crash. Medical device manufacturing was not as affected as other sectors, and was frequently written about as a stalwart. Expanding membership of the EU and other key emerging economies were often blamed for these cuts. Whilst clothing manufacturers such as Fruit of the Loom were upping sticks and moving from Ireland to find cheaper labour, medical devices were viewed to be tied to Europe because of regulatory and safety certification – t-shirts could be made anywhere, but devices for healthcare were tied to European safety standards, making it sensible and cost-effective for companies to keep their manufacturing operations in Ireland.

Despite the optimism reported in newspapers, the medical devices sector was not viewed to have escaped from the dot.com crash entirely unscathed. Faith in the markets had been rocked, and newspapers that had celebrated the power of the markets in the nineties now took a cautious approach: more stories and columns stressed how public-private partnerships were the responsible way forward. Reporting of collaborations between government agencies like the Irish Medical Devices Association and corporations increased after the millennium. Senior figures from the IDA sounded warnings in the press of the dangers of placing too many eggs in either basket: investment, innovation and market disruption were still associated with the markets, whereas security, responsibility and continuity through downturns (such as in 2002) required state involvement. The role of Irish state bodies such as the IDA or the Irish Medical Devices Agency were celebrated for providing infrastructure like technology parks, or attracting funding for technology institutes that trained a skilled but local workforce. Engineering departments based at technology institutes or universities were celebrated in the press for playing their part in developing technologies that were not of interest to the private sector, or playing their role in training a workforce to keep medical device manufacturers in Ireland.

The maturity of the medical devices industry in Ireland is further seen through the greater independence of Irish based subsidiaries, some of whom had broken completely from their parent companies (a future blog post will attempt a comprehensive view of the businesses the made up the medical device marketplace). From the late-eighties onwards reports were common of American companies moving their headquarters to Ireland, and this was conventionally explained through tax incentives, alongside a well invested technology infrastructure and long-established cultural connections between Ireland and the US. From the 2000s onwards, local entrepreneurs secured the backing of large investment capital firms to take over the Irish operations of large US medical device manufacturers. Individuals who secured greater autonomy for Irish operations were celebrated in local and national press for their resourcefulness and ingenuity. One even became a minor celebrity and local playboy: US-Irish medical devices entrepreneur Frank Bonadio frequently appeared in the Irish national press due to his marriage to the singer Mary Coughlan, whom he ended up leaving for Sinéad O’Connor.

Medical devices played a huge role in establishing Ireland’s place on the international industrial stage and formulated a central component of Irish commercial activity. Stories commenting on greater economic independence filtered their way into coverage on medical devices. A number of stories explore geopolitical questions through the medical devices sector. Some reinforced the cultural ties widely viewed to have initially attracted US investment, with one article stating that ‘Irish business IS American’ and describing Irish business as aligning ‘with Boston and not Berlin’ – this is a reference to Boston Scientific, one of the largest medical device manufacturers in Ireland. Others talked about cracks in Irish-American relations: one story on medical devices expressed regret that the pinnacle of US Irish relations between Bill Clinton and Bertie Ahern had passed under George W. Bush, who is described in one article as being ‘no lover of the Irish’. Distancing itself from its old ally, Ireland began to carve its place in Europe as a centre for medical device manufacturing: editorials ran urging a yes vote to the Treaty of Nice, and Irish figures in the medical devices sector interviewed in the financial pages attempted to balance the interests of US investment with a pro-European position.

Returning to the notion of boundary objects having ‘interpretative flexibility’ – this may prove helpful in understanding the role medical devices played in the media. In the articles I have examined, business writers viewed them as holding potential for financial gain, and in education stories, they were viewed as providing an expanding employment sector for technological institutes and universities. Statements and interviews with figures from state development agencies viewed medical devices to be vital to drive economic development by providing clean, safe and secure jobs. Interestingly enough, the views of the clinic are not so well represented in this sample, but a few stories do speak about the potential they offer for improving the efficiency and standards of medical practice. Just as different groups implicitly co-operate through communication with a map, through the medical device different demands converge.

The sense I have from my assessment of articles mentioning medical devices is that within the Irish context, medical devices developed as a cultural icon of national identity in the global economy. It is possible that their operation at the borders of the clinic, investment capital, and state interest translated itself into press coverage from the time. It could perhaps be the case that the meanings spun through these stories on medical devices show how the term brought together older and newer considerations of Irish-ness in the late twentieth and early twenty first century. They also perhaps have an interesting relationship to stereotypical gender roles – although prominent individuals such as Teachta Dála Mary Harney appeared frequently in stories on economic development in relation to medical devices, the business world of medical devices seems to have been a predominantly masculine one during these years – further research on this project may reveal gender bias in coverage.

Written by: Kevin Matthew Jones

Email: kevinmatthewjones@googlemail.com

Funding: Work on this was generously supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award in Humanities and Social Sciences 2019-2024 (Grant No: 212507/Z/18/Z) and a Quality-related Research Grant from Research England.