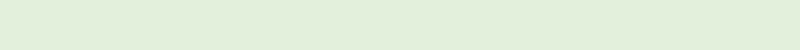

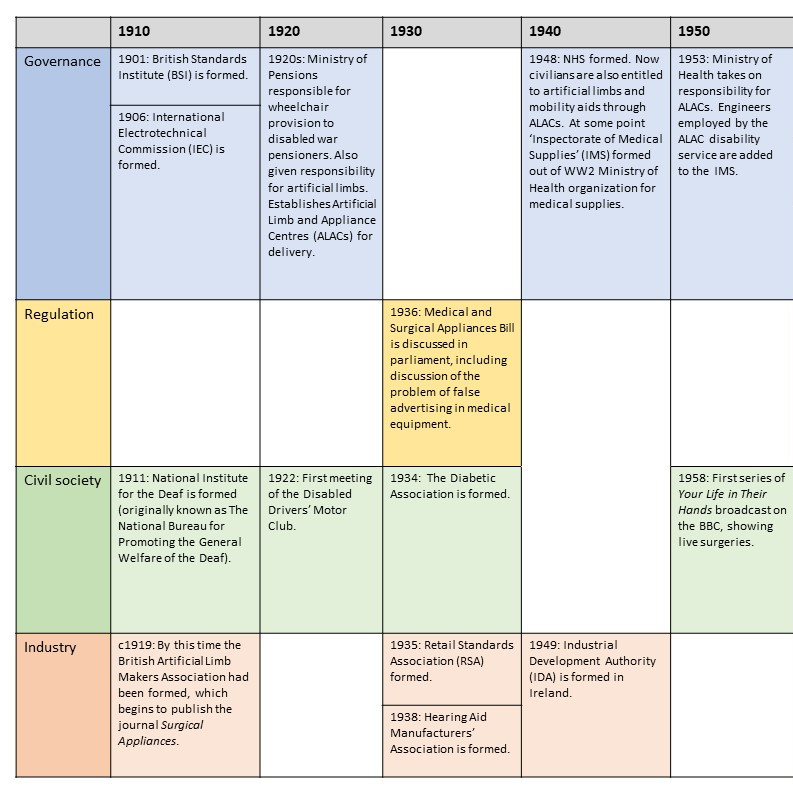

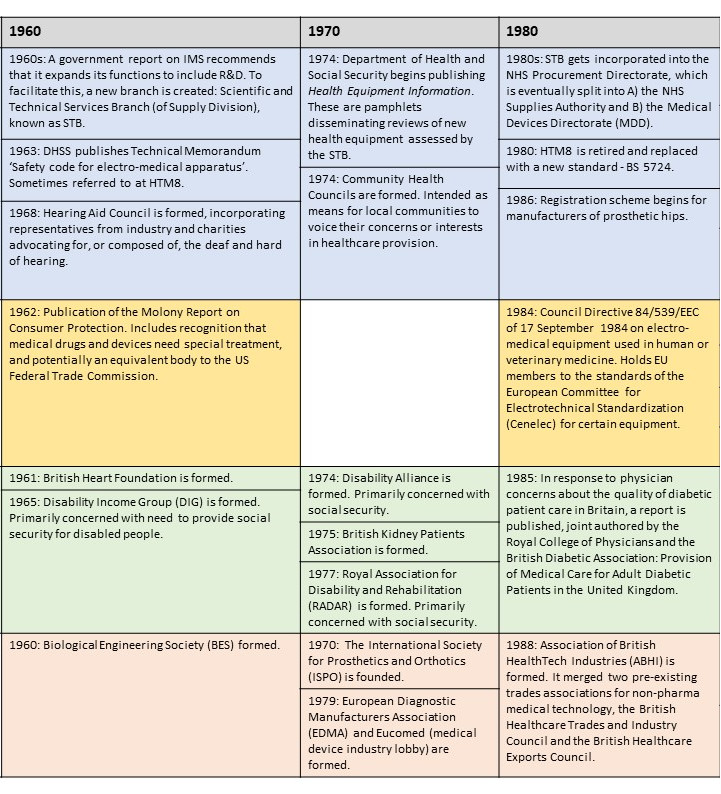

In this post we share a brand new resource of interest to those in, or researching, the field of medical device development.

In the timeline accessible below, readers will find a list of arguably significant historical moments in the creation of the medical device industry as we recognise it today. Some of the motivations behind the creation of this resource, and short commentaries on its contents, can be found below. Most importantly, all of this information is collected together in a 3-fold pamphlet which can be downloaded for free: PAMPHLET.

Introduction

This resource introduces a timeline of key moments in the history of medical devices throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century.

It focusses on two countries in particular, filling up their histories according to four strands: Governance, Regulation, Civil Society, and Industry.

The ambition is to provide a shared focal point for discussion amongst historians, social scientists, lawyers, and philosophers, each presently giving medical devices renewed attention from their different disciplinary perspectives. Rarely do these scholars collectively discuss ‘when’ we are in the history of medical devices. Some seem to assume we are on the edge of an ever-expanding horizon of discovery, others at the apex of a revolutionary new era of data-driven innovation, while others are more concerned about drowning in a sea of marginal iterations, or by the dangers of costly sci-fi utopian imaginaries.

A resource such as this creates candidate historical moments, the significance or insignificance of which can be discussed and debated from many perspectives, resulting in a fresh and multidisciplinary discourse.

Governance

Prior to regulation (see box below) medical devices were sometimes governed by non-statutory methods, including standards, expert assessment, and purchasing policies. In comparison with the UK, less is known about the governance of medical devices in Ireland in this period. It can be assumed that Ireland depended on some of the non-statutory measures adopted, and that medical professionals played the same gatekeeping role (being alert to problems with medical devices), as in the UK.

In the timeline the reader will find examples of institutions, measures, activities, and publications that worked to govern medical devices, with increasing comprehensiveness after the formation of the NHS. Little is known about most of them, and all require further historical scrutiny. The case of the Hearing Aid Council (HAC) is worth highlighting, because the HAC – designed and developed by MP Laurence Pavitt – represents a unique experiment in the governance of a medical technology.

The HAC took responsibility for providing a set of guidelines as to the proper fitting of a hearing aid within the private sector, encompassing the sales strategies that could/could not be adopted, and the protective health measures that were necessary. Its ambition was to ensure purchasers of hearing aids were not taken advantage of. The Council itself was also composed such that less than half of the members would come from industry, the rest coming either from medicine or patient representative bodies. The HAC is a very useful example to think with when it comes to the potential ways to govern a technology.

Regulation

The most useful word to describe the regulatory approach taken towards medical devices in the UK and Ireland prior to the 1980s is ‘voluntarist’. This is because there were no statutory measures regulating this industry prior to that time. Instead companies were expected to adopt best practices, some of which were quite detailed and explicitly agreed with representatives of the NHS or the Ministry of Health. The UK came close to creating legislation giving dedicated attention to medical devices as early as 1968. Early draft materials for what eventually became the 1968 Medicines Act included devices alongside pharmaceuticals, but these plans were dropped.

On the timeline the reader can see that the situation in the UK and Ireland was eventually changed by adoption of new Directives in the EU (then EC, EU from Nov 1993) dedicated to different kinds of devices. The first Directive was approved in 1984, covering electro-medical devices, followed by active implantable medical devices in 1990, and all other medical devices (aside from in vitro diagnostics) in 1993. In vitro diagnostic devices were eventually covered in 1998.

The EU reviewed the overall regulatory landscape created by these pieces of legislation in the 2010s, around the same time as the UK instigated the process of leaving the EU. The regulatory situation in Great Britain and Northern Ireland is now very complex.* While the UK response post-Brexit has primarily been to carry-on with many of the statutory EU arrangements which already existed in UK law, it is not clear what kinds of impact the UK’s exit from the EU will have on; for instance, NHS procurement, the UK’s ability to foster future medical device innovations, to participate in international biomedical and biological engineering research, or the availability of devices developed outside of the country. The long- and short-term effects for Ireland, one of the EU’s most significant producers of medical devices, are also unclear, especially considering the UK’s status as an importer.

*For more detailed commentary: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/everydaycyborgs/2021/02/24/the-medicines-and-medical-devices-act-2021-uncertain-regulatory-futures/

Civil Society

All the while there have been medical devices, there have been patients and people in need of medical or assistive technology. Often those employed in the world of medical device development consider themselves to be the field’s primary catalysts, motivated as they are by the hope of recognition from healthcare professionals and/or commercial success. But this is an unhealthy perspective to adopt. Historians of disability and technology have found abundant evidence of entrepreneurial and design activity taken by those actually using these technologies, particularly when it comes to refining, criticising, or altering technologies sold to them. As such, civil society (which in this context means more specifically patient and disability activist groups, charities, educational organisations) must be placed in a direct parallel with all the other strands explored here. How have disability activists influenced medical device development in the past? What role should they play in the future?

In the timeline the reader will find a number of charities dedicated to particular health conditions, as well as activist organisations dedicated to strengthening the social and political position of people with a disability. Thinking with these groups in mind, and learning about the activities of their leading figures, can help us find potential incongruities or discontinuities in the relationship between technology developers, on the one hand, and ill or people with disabilities on the other. For example, as the historian Gareth Millward* has shown, when the UK government changed its Mobility Allowance policy, enabling more people to purchase an ‘invalid carriage’ through the additional Motability Scheme, it was argued that the alternative cash allowance was much too low, so that the policy privileged and favoured middle class households. Similar controversies surround which technologies are available, and to whom, on the NHS or otherwise.

*Millward, Gareth (2015) Social Security Policy and the Early Disability Movement – Expertise, Disability, and the Government, 1965-77. Twentieth Century British History, 26, pp. 274-297.

Industry

One of the ways that it Is possible to grasp the nature of the medical device marketplace in the UK and Ireland is through a representative sample of the companies that have contributed to it. A sample of 680 of them, the majority in operation after 1970, has been compiled and uploaded to a publicly accessible map. Each entry on the map will tell you the name or names which the company has used, and provides a description of their work: https://blog.bham.ac.uk/everydaycyborgs/2021/05/26/a-ghost-map-of-medical-device-companies-in-the-uk-and-ireland-c-1970-2021/

Readers can find in the timeline some of the moments where these companies recognised themselves as having shared interests, forming into different kinds of trade association. There are also examples of times where government departments have highlighted the industry as particularly worthy of attention. There are also examples of networks or institutions established by engineers, doctors, and scientists for the furtherance of research in the fields of biophysics and biological engineering, which have supported, interacted with, and been supported by Industry in a whole host of ways. These interconnections haveonly received historical attention in a small number of cases.

Timeline

The timeline is best viewed as a PDF, the images below are purely for illustration.

Written by: Dominic J. Berry.

Funding: Work on this was generously supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award in Humanities and Social Sciences 2019-2024 (Grant No: 212507/Z/18/Z).