The professional, vocational, or transferable skills are the make and break of practitioners, coaches, and leaders in performance sport – think communication, teamwork, leadership, as well character and behaviours. University mostly does a decent job of educating students from a technical perspective – they typically know their chops – but often struggles to equip the graduate with that vocational know-how to successfully navigate the demands of the workplace and apply their knowledge. In this article we consider both sides of the skills tables – Industry and Academic – and use the opportunity of the 30th Anniversary of BASES to reflect on how the performance sport industry has changed over the decades, as well as highlight the value of work-based learning to help prepare the graduate for work.

I write this from the 2023 BASES Conference, which this year is being hosted at the Coventry City FC stadium – the Coventry Building Society Arena. BASES – the British Association of Sport and Exercise Science and the professional body for the discipline in the UK– is having its 30th Anniversary. However, its origins are a little earlier, having been founded in 1984 as BASS – the British Association of Sport Science – to reflect the growing need for structure, for promotion and facilitating collaboration across the sport science disciplines in the early days of our industry.

And crikey, has the world changed since! In what was once largely in the domain of academia, the last 30 years have seen significant developments in the professionalisation of sport science and of exercise science. The establishment and growth of a practitioner community across not just science but all aspects of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Medicine); of the structure, systems and operation of sport and the leadership of this; of the research and innovation sector; and of the commercial sport science. All these burgeoning sectors of the industry have shaped the British sport and exercise STEM collective into the industry it is now, and have pulled it, not just kicking and fighting into the 21st century, but punching significantly above its weight. Particularly in the Olympic and Paralympic arena, the advent of National Lottery investment since the Sydney 2000 Games has moved the industry on to a whole new realm of sporting success, ambition, and operation (think UK Sport and the English Institute of Sport, now UK Sport Institute). The expectation has shifted too. The professionalisation of sport – of all sports – has seen the sport STEM industry become far more professional itself and in turn, consequential and demanding. Funders want return for their investment; coaches want know-how to support decision making; athletes and players want expertise to support their development; leaders want business development thinking to support their strategizing.

But has the academic sport science sector moved on accordingly in the last 30 years? And importantly, has the readiness of our graduate pool risen to this challenge of professionalism and their preparation allowed for that? I would say the fair and honest answer to that is, it is quite mixed. Or at least, it is quite polarised with examples of high quality and some not so. I am here at BASES this year with my old friend and colleague, Dr Steve Ingham. We are running a workshop on one of our shared passions. That is, the work-readiness of graduates to step into the performance sport sector. Steve’s ‘Letter to the 15,000’ – an annual clarion call to thousands of sport-ex graduates – above all extols the virtues (as well as vital need) of their professional, vocational, and transferable skills. Skills that will prepare them for whatever job or industry they find themselves. The title itself indicates the size of the challenge (circa 15 K graduates each year in sport related courses), and that the talented graduate must do more to stand out from the growing crowd. The talent is undoubtedly there – our extensive survey of industry this year reveals that the technical knowledge of graduates is as good as it has ever been. But being ready for the workplace is more than solving a technical equation. Being excellent communicators, being a trusted team player, and being dependable, reliable and an all-round good egg stand out as far more important for most industry employers. Indeed, three-quarters of survey respondents indicates that they would make a recruitment decision on these vocational factors first before considering the technical chops of the graduate.

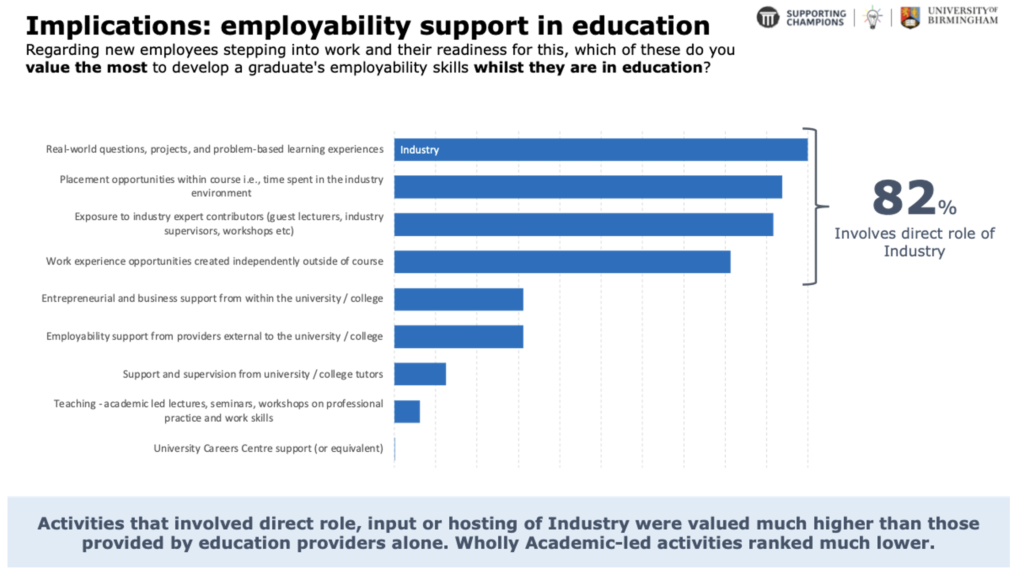

Work-based learning is, by far and by all, identified as the most valued driver of transferable skills development. Learning must mean something – purpose and context, and above all consequence – and the authenticity of the task and hence the direct collaboration of industry with academia through placements and projects is the backbone of this. This has implications for curriculum design from undergraduate courses all the way through to professional doctorates for industry professionals – something we lead on at the University of Birmingham through our Graduate School for Sport and Professional Practice. It is not an easy challenge – the capacity of institutions to provide a credible learning experience takes both resourcing and a strong structure to rest upon. But the value is undeniable, and those who can rise to the challenge that our Industry is setting (and it will only continue to rise higher), will stand out in a crowded market for all the right reasons.

J.Pringle@bham.ac.uk