A very important purpose of research is the impact it makes: how much publicity does it get, and whether it prompts a change in policy. As a retired commercial solicitor and mediator, I did not write my PhD to start an academic career, but as a vehicle to achieve that impact – and to change the world. But my experience has been that I have found it very difficult to make that impact by getting through to politicians and journalists. This blog explains how that came about.

I was very pleased to be accepted as a PhD student at Birmingham Law School between 2013 and 2017. My research was supervised, very ably, by Professors Richard Young and Simon Pemberton. My subject was the inadequate regulation of police conduct in custody suites. I had discovered this problem by volunteering as a custody visitor, under the statutory Independent Custody Visiting Scheme. At that time I did not have any intention of writing about the scheme. But working as a visitor made me feel uneasy about the scheme, so I looked for academic literature about it; finding that there was none, I decided to write a thesis about the scheme. I carried out desk research of the history of the scheme and a local case study. I conducted 51 hours of face-to-face semi-structured interviews with visitors, police officers, custody staff, defence solicitors, administrators, and, most significantly, the detainees themselves. I carried out 123 hours of observation of visits made by custody visitors and of what happens in custody suites when visitors are not present. My book based on the thesis was published in 2018.[1] I also published an article about the techniques used in the observation in 2020.[2] The techniques included looking out for what does not happen as much as what did happen. I constructed a programme of the tasks that visitors would need to carry out to do their job as regulators properly, and looked out to see whether they did, or did not, carry out those tasks.

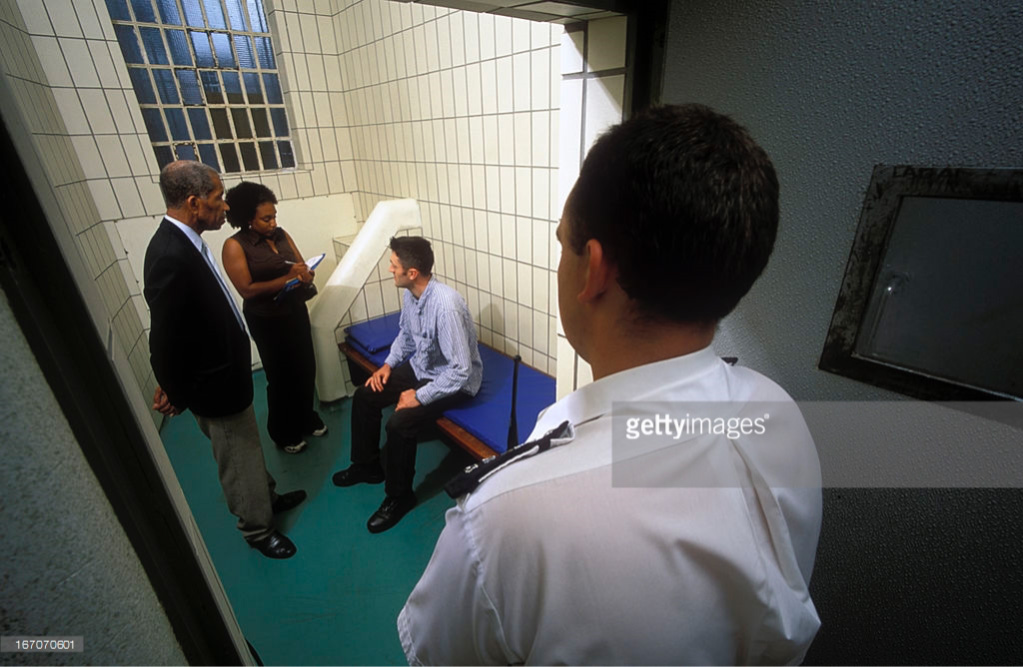

The visiting is supposed to safeguard detainees, but I found it be a toothless watchdog, neither independent nor effective. The defects in the scheme are vividly illustrated by this photograph of an actual visit. The meeting between the visitors and the detainee is being supervised by a member of the custody staff. The detainee is most unlikely to tell the visitors anything confidential, particularly if it is about how s/he has been mistreated while in custody.

Recent adverse publicity[3] about police misconduct has shown that the police need more effective regulation. The police are largely self-regulated. Effective regulation of police conduct in custody suites is supposed to be provided by the Independent Custody Visiting Scheme. Under a United Nations treaty,[4] the UK is required to set up systems for safeguarding various categories of persons detained by the state. Custody visiting is the body charged with safeguarding detainees in police custody. Custody visitors are therefore regulators of police conduct in custody suites. However, the scheme is unable to operate effectively. Why is this the case? The answer is that, ever since the scheme’s inception in the 1980s, all the evidence points to its having suited governments, whether conservative, labour or coalition, that custody visiting fails to operate effectively. Custody visiting was not a brainchild of government. It was Lord Scarman’s 1981 report on the Brixton riots, adopting Michael Meacher MP’s ideas, that recommended custody visiting: the conservative government refused to implement any part of the report. The government in 1984-6 was then confronted with demands for a visiting scheme from activists in Lambeth. The original Home Office Circular about the scheme made it very clear that the scheme was to cause the police as little trouble as possible. Nothing has happened since then for there to have been any retreat from this position. Absent from all government documents is the characterisation of the scheme as a regulator of the police and a deterrent to police misconduct which might lead to death.[5] The silence is deafening. Alongside this government policy, the other vital factor in this process is the power of the police, which, subconsciously and successfully, discourages the visitors from challenging the police.[6]

How the police manage custody certainly gives serious cause for concern. Some 20 detainees die in police custody each year. To give an idea of how bad police misconduct in custody suites can be, short of actually causing death, take a look at how the police treated Dr Konstancja Duff. Dr Duff is an assistant professor of philosophy, specialising in the politics of crime and policing, at the University of Nottingham. The details of the story are taken from the account in the Guardian on 24 January 2022. Dr Duff was arrested on 5 May 2013 on suspicion of obstructing and assaulting police after trying to hand a legal advice card to a 15-year-old caught in a stop-and-search sweep in Hackney – allegations she was later cleared of in court. The CCTV footage of the north-east London police station custody area on the day she was searched shows the senior officer telling officers to show her that ‘resistance is futile and to search her by any means necessary’. ‘Treat her like a terrorist’, he said, ‘I don’t care’. In a cell, three female officers bound Dr Duff by her hands and feet, pinned her to the floor and cut her clothes off with scissors. ‘What’s that smell? Oh, it’s her knickers’, officers said to each other, after Dr Duff was held down on the floor and her clothes cut off.

Dr Duff described the ordeal, which left her with a number of visible injuries, as like a sexual assault. But Dr Duff said individual officers were not the issue. She said the exchanges shown in the CCTV exposed ‘the culture of sexualised mockery, the dehumanising attitude’ shown during her strip-search. Officers’ taunts of her in the cell, out of view of CCTV, were worse than those captured on camera, she said. ‘The crucial issue is that racism, misogyny [and] sexual violence, are normalised in policing’. Nearly nine years later the Metropolitan police have finally apologised and paid compensation to Dr Duff for ‘sexist, derogatory and unacceptable language’ used by officers about her when she was strip-searched.

There are clearly very serious issues of deeply embedded culture here which cry out for action. But custody visiting would make an impact on police misconduct, if it had regulatory teeth. If the police knew that custody visitors could turn up at the police station at any time without warning, and that they would have the right to enter the custody suite immediately and to report directly to the public, the police would be less likely to carry on in the way they did with Dr Duff. But the scheme does not operate that way, and it fails to make any impact on police behaviour. That is why custody visiting matters, and why reform is urgently needed.

In 2018 I was introduced to Yvette Cooper MP, then chair of the Home Affairs Select Committee, who expressed interest in my work. Yvette Cooper recommended that I lobby other members of the committee. I managed to get a meeting with only one Home Affairs Committee member, Tim Loughton MP. He told me that the problems I had identified with the scheme werenʼt sufficiently eye-catching. He also said that you couldnʼt point to any one death in custody and say it would have been prevented by an effective custody visiting scheme. It occurred to me later that if this argument were applied to regulation generally it would undermine the whole system of regulation. Regulation is about preventing, or at least reducing, harm to society. No proposed system of regulation should be condemned, in advance of its operation, on this basis. I had no substantive response from any of the other politicians and journalists I sent emails to.

I made many serious criticisms of the visiting scheme, and I was tempted to conclude that the best thing would be to scrap it, but then decided that it could be possible for the scheme to do a lot of good if it were radically reformed. Some of the reforms would require a change in the law, principally those designed to ensure the scheme’s independence from the Police and Crime Commissioners. I prepared a list of reforms which would not require a change in the law. Yvette Cooper suggested that these reforms could be piloted in a police area. Here some of the more important ones: all of them seek to remedy serious defects in the scheme.

- Applicants to join the visiting scheme must not be disqualified automatically because they have a criminal record.

- Trainers. All visitors must be briefed by the range of the professionals who are involved in custody, including defence lawyers and former detainees.

- Visitors must have the right not to be dismissed without a court order.

- Independent voice. Visitors must be allowed to make public statements without the permission of the Police and Crime Commissioner.

- The scheme must state that the purpose of custody visiting is the protection of detainees, and that its overriding purpose is to reduce the number of deaths in custody.

- Deaths in custody. Visitors must be trained about what happens when a detainee dies in custody, and about the inquest process.

- Visitors must refer to detainees as detainees, persons in custody or suspects, but not as prisoners.

- Conduct of visits. Visits must be genuinely random to ensure maximum effectiveness. Visits must be made at all hours and days of the week.

- Pass keys or codes. Visitors must be given pass codes or pass keys to the custody blocks they visit.

- Access to all detainees. Visitors must be able to meet each detainee, subject only to veto by a written order of an inspector.

- Detainees in police interview. Visitors must have the right to require a suspension of a police interview while visitors hold a meeting with the detainee.

- Location of meetings with detainees. Meetings between detainees and custody visitors must include an inspection of the cell and then move to a safe, private consultation room.

- No supervision of meetings. The custody staff must not be able to overhear or to make close observation of meetings with detainees.

- Visitors’ dealings with detainees. Visitors must give sufficient time to the meetings with detainees, act on any concerns or complaints expressed, and provide the detainees with feedback about the actions taken and the results achieved.

- Visitors must carry out all the following checks thoroughly, and when necessary ask the police the questions that need to be asked. These include: the level of staffing: whether the CCTV is working: requiring the removal of ligature points: ensuring that all staff are carrying ligature knives: ensuring that appropriate toiletries are available for both female and male detainees: ensuring that all detainees know that they can take showers.

- Visitors must be trained and encouraged to challenge the police when it is appropriate to do so: for instance, to ask why a detainee has (or has not) been taken to hospital.

- Communicating with defence lawyers. Visitors must be able to telephone defence solicitors about their clients whom the visitors have seen in detention.

- No enforced disclosure. The police must undertake not to enforce disclosure of information given by detainees to visitors of the type that would be subject to legal professional privilege.

- Complaints. If detainees did wish to make complaints against the police, custody visitors must be able to facilitate the process.

- Visitor panel meetings. Visitors must meet at locations other than police and Police and Crime Commissioner premises, and without representatives of the police and the Commissioner always being present.

- Reporting system. Visitors must be able to access their own reports and communications between the local scheme organiser and the police.

I suggested a pilot to a Police and Crime Commissioner. At this point ICVA became involved. ICVA is the Independent Custody Visiting Association, which sounds like an organisation representing visitors, but in fact its only members are Police and Crime Commissioners. ICVA consulted the Home Office and the Association of Police and Crime Commissioners: as usual, no representative of detainees was consulted. ICVA concluded that the proposed pilot would not be effective in solving the issues it aimed to address, and they were therefore unable to support it. Despite that, ICVA also stated that much of their work would address some of the issues that the research had highlighted. Those issues would of course have been addressed in the pilot, had it been allowed to take place.

During my meeting with him, Tim Loughton prompted me to write to the Home Secretary (then Sajid Javid) about my research. The Home Office’s response (their letter was neither signed nor dated) was that the most effective means of ICVA delivering change was through ICVA’s grant agreement with the Home Office which allowed a ‛strategic overview’ of improvements. The Home Office went on to say the issues highlighted by my research were being addressed by many of the new approaches and improvements which ICVA and Police and Crime Commissioners were implementing as part of their current business plan, and that ICVA would consider my work, along with other research concerning independent custody visiting, in developing their future business plans. However, ICVA have not published any information about this. ICVA and the Home Office have declined either to comment on the individual issues raised by my research or to discuss any of those issues with me.

I kept in touch with the committee, and in September 2020 the clerk emailed to say that the committee was initiating an inquiry into police complaints and conduct, with specific reference to whether further reforms (ie beyond reforms to the complaints system) were required to secure public confidence in the police conduct and discipline system. The committee invited me to submit evidence relating to this issue, which I sent in in October 2020.

The committee published my evidence, and there were four sessions of the inquiry in spring 2021. I was not asked to participate. Then in the autumn of 2021 the clerk told me the committee were writing their report. In December 2021 Yvette Cooper left the committee on her appointment as Shadow Home Secretary. The report was published on March 1 2022.[7] The report is a valuable account of the inadequacies of the police complaints system, with some useful recommendations, but it contains no reference to the point on which I was asked to contribute. The committee’s operations manager has confirmed to me that there is to be no further report resulting from this inquiry.

The Home Affairs Committee could have made recommendations which would have publicised the issues raised by my research, that is giving them impact. Those recommendations would also have put pressure on ministers to confront those issues and to make changes to the custody visiting system. I believe that if the ineffectiveness of custody visiting were widely known among politicians and journalists, there would be a push for the much needed reform of the scheme. Apart from that, I believe that the implications of my research go much wider than what happens in police stations, very important as that is. My research is about how the power of the state obstructs the protection of the human rights of vulnerable citizens. The former judge of the Court of Appeal, Sir Stephen Sedley, endorsed my book as follows: ‘This innovative and objective study of the system of external supervision of police custody, and of its failure to let daylight in, should alert everyone concerned with the tension between authority and liberty.’

[1] Regulating Police Detention: Voices from behind Closed Doors

https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/regulating-police-detention

[2] ‘Custody visiting: the watchdog that didn’t bark,’ Criminology and Criminal Justice, October 30, 2020, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1748895820967989

[3] For instance, the Hotton report: https://uk.search.yahoo.com/yhs/search?hspart=trp&hsimp=yhs-001&type=Y149_F163_202167_081020&p=Hotton+Report

[4] Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT).

[5] Regulating Police Detention, Chapter 2.

[6] Regulating Police Detention, for instance at pp4-6, and 25.

[7] https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/9006/documents/159114/default/