Alice Pugh discusses the impact that short-term policy and overly complex government structures have on local economic development in the UK, and how devolution has somewhat shielded the devolved nations from this situation.

Policy churn and short-termism are endemic within the UK policy context – policy agendas, funding streams and institutions are continuously recycled in and out of existence. Since the 1980s place-based policy has been a focus of successive governments, with governments rolling out a multitude of place-based policies and programmes to tackle inter and intra-regional inequalities.

However, often these policies and programmes last little more than a few years. In part, this is a result of new governments being elected and opting to replace the previous government’s place-based policies with their own. This can be seen in Figure 1 below, where new governments are elected, represented in the figure by the coloured lines (Red=Labour, Blue=Conservative, Yellow=Coalition). The churn in policy, however, is not just prominent between governments of different parties, but between governments of the same party. This has been particularly noticeable since 2015/16, following the instability within the conservative party in central government, alongside economic shocks such as Brexit and the pandemic.

Figure 1: England Place-based Economic Development policies and programmes 1992 to 2024

This chopping and changing of policy often results in devolved national, regional and local institutions being thwarted in the creation of a long-term strategy, instead having to piece together fragmented funding streams into a disjointed, unstable strategy.

Alongside this, policy churn frequently leads to institutional churn, at a place level which, in turn, can create significant institutional memory and knowledge loss, leaving a lack of understanding as to ‘what works’ in place-based initiatives. This can be seen in Figure 2 below, where over the last 30 years in England, there has been a shift from Training and Enterprise Councils (TECs) to Regional Development Agencies (RDAs), Local Enterprise Partnerships (LEPs) and Combined Authorities, amongst other institutions that have been established then abolished. Overall, churn and short-termism mean that it is difficult for place-based policy makers to deliver transformative change.

Figure 2: Place-based Economic Development Institutions in the UK from 1992 to 2024

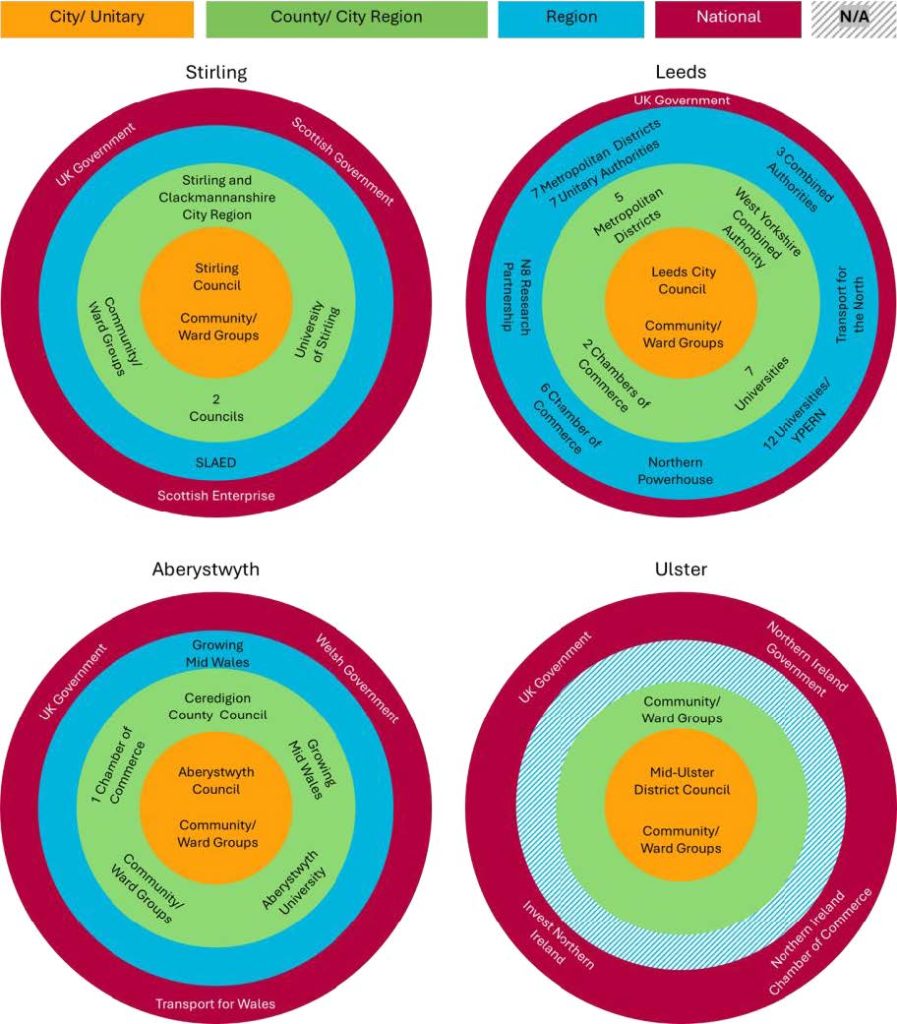

The establishment of the devolved nations as distinct political and institutional areas has led to a differing institutional landscape, particularly as economic development was devolved to the nations. This has somewhat insulated the devolved nations from the churn and instability of central government economic development policy. This is demonstrated well in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 is a simplified version of the governance structures that exist around four local authorities in the UK – Stirling, Leeds, Aberystwyth, and Ulster. The centre of the structure is the city/unitary authority tier, followed by the county or city region tier, then the regional tier and finally the national tier.

As can be seen in Figure 3, when comparing governance structures within place, there is an over-proliferation of governance institutions within Leeds and the wider Yorkshire and Humber region. The economic development structure of Leeds is far more complex than for the geographies within the devolved nations. In Leeds, there are numerous bodies across the varying tiers of governance. Often these institutions geographically and strategically overlap, creating a lack of coherence in the purpose of these institutes. This complexity within the regional and local landscape can lead to significant issues in the effectiveness of these institutes. Often incoherence around the powers, responsibilities and roles of place-based institutions can lead to considerable issues in accountability, duplication of effort, and efficiencies. Tensions can also subsequently arise between regional and local institutions around powers, roles and responsibilities which can create difficulties in partnership working.

Figure 3: Comparison of governance structures across four example areas

A greater challenge for the devolved nations is a missing middle. Research has found that in many places within the devolved nations, there is a middle layer missing between the national and local government, bodies which can work with local-level actors and represent their views devolved national or even central government.

However, the devolved nations are not entirely unaffected by the central government’s economic development policy choices. For instance, even though the devolved nations largely have discretion over economic development within their areas, the level of this discretion can be impacted by the central government of the day. For example, during levelling up the devolved nations received minimal consultation as to how this economic development funding should be spent within their geography, with the policy and fund being imposed upon them rather than developed with them through consultation.

Generally, the churn and short-termism at a national level often create instability which filters down disrupting progress at a sub-national level. This constant ‘reinvigoration’ of place-based economic development policy, strategy and funding, leads to weak, piecemeal strategy and policy at a local place-based level as sub-national government is forced to piece together unstable, short-term economic development policy. This is worsened when the churning instability and ad hoc approach to devolution have created a complex network of sub-national capacities and capabilities, particularly within England.

However, despite these challenges, sub-national institutions are often best placed to tackle the unique needs that face their place and thus greater devolution of powers and funding is needed to support place-based organisations to create transformational change with regards to inclusive and sustainable local economic development. The model for devolution will need significant consideration focusing on the improvement of the structure, funding and resources of devolved national and sub-national governments to guarantee the capacity and capability to create effective change.

This blog was based on research conducted within the Inclusive and Sustainable Local Economic Performance Evidence Review.

This blog was written by Alice Pugh, Policy and Data Analyst City-REDI, University of Birmingham.

Find out more about the Local Policy Innovation Partnership Hub.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the author and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.